Curriculum for gr. 6-8

Compiled by Dan Harper, v. 1.0. With thanks to the many talented Ecojustice Class teachers over the years, including Carol Steinfeld, Francesca Finch, Emma Grant-Bier, Ed Vail, Lorraine Kostka, Buzz Frahn, Mark Erickson, and many more.

Copyright (c) 2014-2022 Dan Harper

Plan ahead

Ecojustice Class is a hands-on class that spends as much time outdoors as possible. Because many of the activities are meant to be done outdoors, you’ll have to plan around your location’s seasons and weather.

We developed this class in northern California, and during rainy season we always had a back-up plan in case we had to stay indoors. Other factors can affect your plans, e.g., fire building might have to be canceled during an air pollution alert (“spare-the-air day”). Some activities, like gardening, are seasonal.

In short, you’ll want to plan out a year’s worth of classes, with back-up plans in case of adverse weather.

Contents

Ecojustice Class Lesson Plans

Ecojustice Elders

Ecojustice major projects

If you want some theory, keep reading on this page. Otherwise, go straight to the lesson plans using the link above.

What Is Ecojustice

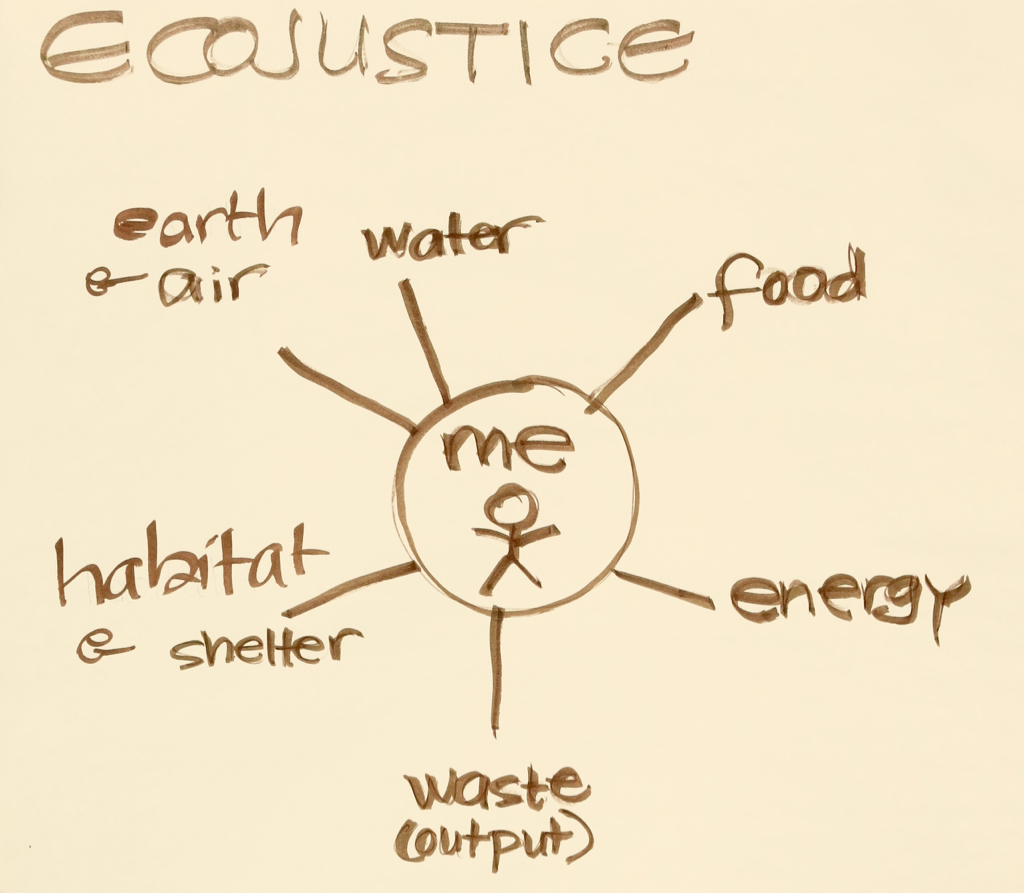

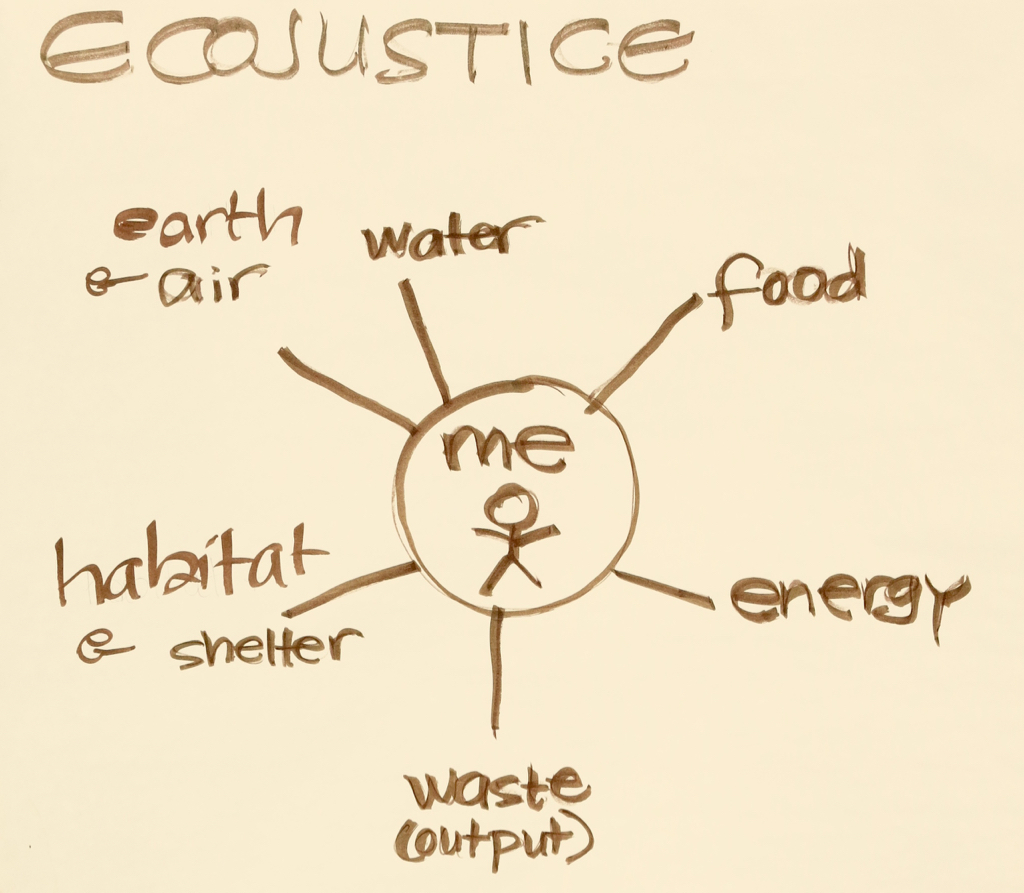

Here’s a sign we post in the class meeting area to explain what ecojustice is:

And here’s an image one of our teachers used to explain ecojustice:

Principles of Ecojustice

Ecojustice is another name for Environmental Justice. The principles of Environmental Justice were outlined by delegates to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit held on October 24-27, 1991, in Washington, D.C.:

1) Environmental Justice affirms the sacredness of Mother Earth, ecological unity and the interdependence of all species, and the right to be free from ecological destruction.

2) Environmental Justice demands that public policy be based on mutual respect and justice for all peoples, free from any form of discrimination or bias.

3) Environmental Justice mandates the right to ethical, balanced and responsible uses of land and renewable resources in the interest of a sustainable planet for humans and other living things.

4) Environmental Justice calls for universal protection from nuclear testing, extraction, production and disposal of toxic/hazardous wastes and poisons and nuclear testing that threaten the fundamental right to clean air, land, water, and food.

5) Environmental Justice affirms the fundamental right to political, economic, cultural and environmental self-determination of all peoples.

6) Environmental Justice demands the cessation of the production of all toxins, hazardous wastes, and radioactive materials, and that all past and current producers be held strictly accountable to the people for detoxification and the containment at the point of production.

7) Environmental Justice demands the right to participate as equal partners at every level of decision-making, including needs assessment, planning, implementation, enforcement and evaluation.

8) Environmental Justice affirms the right of all workers to a safe and healthy work environment without being forced to choose between an unsafe livelihood and unemployment. It also affirms the right of those who work at home to be free from environmental hazards.

9) Environmental Justice protects the right of victims of environmental injustice to receive full compensation and reparations for damages as well as quality health care.

10) Environmental Justice considers governmental acts of environmental injustice a violation of international law, the Universal Declaration On Human Rights, and the United Nations Convention on Genocide.

11) Environmental Justice must recognize a special legal and natural relationship of Native Peoples to the U.S. government through treaties, agreements, compacts, and covenants affirming sovereignty and self-determination.

12) Environmental Justice affirms the need for urban and rural ecological policies to clean up and rebuild our cities and rural areas in balance with nature, honoring the cultural integrity of all our communities, and provided fair access for all to the full range of resources.

13) Environmental Justice calls for the strict enforcement of principles of informed consent, and a halt to the testing of experimental reproductive and medical procedures and vaccinations on people of color.

14) Environmental Justice opposes the destructive operations of multi-national corporations.

15) Environmental Justice opposes military occupation, repression and exploitation of lands, peoples and cultures, and other life forms.

16) Environmental Justice calls for the education of present and future generations which emphasizes social and environmental issues, based on our experience and an appreciation of our diverse cultural perspectives.

17) Environmental Justice requires that we, as individuals, make personal and consumer choices to consume as little of Mother Earth’s resources and to produce as little waste as possible; and make the conscious decision to challenge and re-prioritize our lifestyles to ensure the health of the natural world for present and future generations.

Philosophy and Theology of Ecojustice Class

(This is the text of a presentation Dan Harper made in 2016 at the “Sacred Texts, Human Contexts” conference on “Nature and Environment in Religions, that describes some of the thought and feeling behind what we do:)

How can sacred texts support environmental justice? How can sacred texts help us solve the problem of global environmental disaster? I appreciate the scholarly work that has been done in this area, but I find a gap between scholarly work and the reality of people’s lives in our local congregation.

Both I and most of the people in our congregation find ourselves busy raising children, going to school or working at jobs or coping with unemployment, caring for aging parents or declining spouses, etc., activities which leave little time for reading or study. From one point of view, these mundane human activities crowd out the divine. But the poet Marge Piercy, in a poem we sometimes read in our worship services, says:

Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure: Make love that is loving.

Keep tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.

We could try to clear a straight path through the thickets and brambles of ordinary life, to cut through the thickets that lie between sacred text and our lives. But as a religious educator, I have found direct connections never work as well as “tangling and interweaving and taking more in.” So let me introduce you to the “rabbit runs and burrows and lairs” of our congregation’s religious education program, with its interconnections spreading like tangled rhizomes of plants — documenting how a real-world congregation resists “an artificial unity” and instead celebrates “the messiness of becoming.”

Please note that in this presentation I protect privacy by changing names and personal details, except where I have permission to quote.

Our local faith community, the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA), is are most conveniently classified as a “post-Christian” congregation — formerly Christian, but no longer considered so.

Sunday mornings, I stand outside the door to our Main Hall, greeting people as they come up from the parking lot and bike racks. On a recent Sunday morning, Reva, age 12, and her father wave at me as they walk up from their electric car. Reva’s family is committed to fighting climate change, and they purchased an electric Nissan Leaf soon after the car came on the market. This family is typical of many Silicon Valley families in the congregation: the children are well-versed in STEM learning, and families show their commitment to the global environmental crisis by embracing new technological solutions.

All our children and teens spend the first fifteen minutes of every service in the Main Hall before they go off to Sunday school. Three sixth grade girls, Zoe, Becky, and Eva, say “Hi!” to me as they race through the door to take up their usual places in the back corner of the Main Hall, as Amy Zucker Morgenstern, our senior minister, begins the worship service. Beverly, the lay worship associate, says: “With our centering words each week, we draw on the many sources of our living tradition,” then reads a short excerpt from a contemporary poem. I’m standing next to where Zoe, Becky, and Maria are sitting quietly interacting through gestures and facial expressions; I’m pretty sure they didn’t heard the centering words.

Everybody stands to sing the first hymn together, a contemporary spiritual song called “Come Sing a Song with Me.” One fifth grader stands on her chair, holding on to a parent, leaning her head back, her whole body involved in singing this, her favorite song. After the hymn, I open the side door, and forty or so children run pell-mell out the door and across the patio towards their Sunday school classrooms. On this Sunday, the children going off to Sunday school are about 75% white; the non-white children at UUCPA are mostly East and South Asian descent, but also African, Latino/a, & Middle Eastern descent. Economically, the majority of the regular attendees of UUCPA have incomes that place them in the middle class and upper middle class, but some regular attendees are in the lower middle class.

In the sixth grade Ecojustice class, I take attendance while Lorraine, my co-teacher, asks one of the children to light a candle in a chalice (a flaming chalice is a common symbol for Unitarian Universalism). /[6] The children all say our usual opening words together: “We light this chalice in honor of Unitarian Universalism, /[7] the church of the open minds, helping hands, and loving hearts,” and we all do the hand motions that go with each phrase.

Today we’re going to work on making nesting boxes for the Violet-green Swallows that fly over the creek that flows along the edge of the church campus. But first the children want to check on their worm composter and their “recycled container garden” made from a worn-out automobile tire and discarded wood pallets. We make a stop at the church kitchen to pick up some vegetable scraps for the worms. Eva reaches into the composter and pulls out some worms to show the others [see the photo at the beginning of this essay].

The worm composter and the tire garden are right next to Adobe Creek, and some of the children look down to see how much water remains from the rain we had last week. Adobe Creek flows for about 14 miles from Black Mountain, a peak on the Monte Bello Ridge west of Palo Alto, to San Francisco Bay, draining about 10 square miles of land. The creek runs in a concrete channel for its last two miles, including the stretch past the church. The children stretch over the chain link fence to look. Water just covering the bottom of the creek flows quickly past. One of the children points at a pair of Mallards in the water.

Every time we visit the worm composter and the tire garden, we look in the creek. We want the children to feel connected to our local watershed. Anabaptist theologian Ched Myers argues that too often environmentalists and eco-theologians tend to think in broad abstractions while neglecting their immediate ecological context, a tendency that can lead congregations to engage in environmental justice work that is merely “cosmetic.” Myers wants religious communities to engage in what he calls “watershed discipleship,” environmental justice centered on the bioregion of their local watershed and rooted in scripture, in the Bible; though he is careful to add that the natural world is a kind of scripture. Myers’s notion of “watershed discipleship” is a little abstract for our sixth graders, and too Christian for our post-Christian congregation, but it helps explain why I and the other teachers insist on taking the children to see dirty water flowing through a concrete channel.

We go back to work on the half-finished nesting boxes. Before we start working, I bring up our conversation from the previous week, about House Sparrows, an invasive species, who sometimes take over nesting boxes, thus depriving native swallows of nesting habitat. Last week, I had told the children that ornithologists recommend removing and destroying House Sparrow nests in swallow nesting boxes. The children did not like the idea of destroying House Sparrow eggs, even if theses birds are a destructive invasive species. This week I admit that I probably couldn’t destroy a House Sparrow nest myself, and I ask what they think we should do. Zoe finally says she would be willing to remove a House Sparrow nest, though she wouldn’t destroy it, she would put it on the ground somewhere. “What if a cat gets the nest?” asks Toby. “Well, at least we didn’t kill it,” Zoe says.

This is our third week building nesting boxes. By now, most of the children know what to do. Even Catalina, who hadn’t worked on the nesting boxes before, is taken in hand by some of the other girls, who show her the plans, and some partially assembled nesting boxes. We keep working until the worship service ends. Frank, an older adult, happens to walk past us, and stops to see what we are doing, and soon he is working, too. Finally Lorraine and I have to end the class.

“OK, everyone stand in a circle and hold hands,” I say. When everyone is in a circle, I ask everyone to say one thing that they learned today: “Sawing is hard.” “I learned how to drill.” “Our worms are happy.” Then we all say the unison benediction the adults say at the end of each worship service:

Go out into the world in peace

Be of good courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return no one evil for evil

Strengthen the faint-hearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Rejoice in beauty

Speak love with word and deed

Honor all beings.

This benediction comes from 1 Thessalonians 5:13-15, 21-22, and is further adapted by our senior minister. The children have memorized it; their comments make it seem that they have thought about its meaning. I suspect that some of them would be displeased to learn that the benediction they like so well comes from the Bible.

Many of these children are from families in the middle of what political scientists Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell call “a gaping chasm between those who are highly religious and those who are highly secular.” They fall in the middle because they’re both secular and religious at the same time. I have learned from listening to and talking with the children and teens that most of them think of “religious” persons as intolerant; in this, their views correspond to the views Putnam and Campbell have found in highly secular Americans. Yet the sixth graders in this class are “religious” if we measure religiosity, not by belief in God or prayer, but by regular attendance in a local faith community. Some of them are aware of their awkward status as both religious and secular, and say they don’t like telling their friends they go to church because it’s hard to explain that their church doesn’t make them believe in God.

After the closing circle, several children volunteer, without being asked, to stay and help put away tools and materials. It takes fifteen minutes to get everything put away, and some of the children linger on, ready to stay longer if there is something to do. These sixth graders show no resistance to the religious bioregionalism of Ecojustice class; exactly the opposite: they like to know how they are connected to Violet-green Swallows, to Adobe Creek, to worms and compost.

Why do they like this class so much? Late last year, I overheard a conversation where a seventh grader told a fifth grader, “You’ve got to take the Ecojustice class. You actually get to do things.” When he said “You get to do things,” that seventh grader — who happens to be a non-praying atheist — did not mean his friend would get to pray or read sacred texts. He had grasped that the curriculum of Ecojustice class is based on a progressive educational philosophy where “the learning experience is a part of life, not a separated preparation for life.” While we aim to inculcate religious literacy, including familiarity with sacred texts, these things cannot be taught separately from the lives we are in the midst of living.

Our progressive educational philosophy cause us to look with alarm at the seeming inability of local faith communities to address the global environmental crisis. We all know people of faith have to address the global environmental crisis, yet in spite of this apparent consensus “that religion must play a central role in building a more environmentally sustainable society, religious organizations and individuals have achieved few tangible results.” Religions have done pretty well at linking their sacred texts and traditions to abstract thinking about environmental justice, but this does not seem to have had much effect in the real world. The specific conditions of the global environmental crisis require a new approach to theology; sacred texts cannot be treated separately from the immediate reality of our lives. To put this more directly: when I asked a group of elders at UUCPA about sacred texts and environmental ethics, one replied, “You don’t get your ethics by reading,… you get your ethics by living.”

Words — whether spoken or written words — are not going to be the most important teaching tool. In U.S. culture, we often equate teaching with explaining, which “makes teaching a talkative affair” where we assume that “to teach is to tell.” But this assumption is not accurate, because most teaching is actually nonverbal teaching. Example and experiences will always prove more powerful than speech: “No amount of talk can substitute for the well-placed gesture of the human body.”

The teaching that takes place in the Ecojustice class is always connected with bodily movement and gesture. Before the class even begins, the children take part in the worship service, sitting near to other people of all different ages, standing up to sing, running out the door to their classes. When we arrive in the classroom, we sit in a circle so that we are aware of each other’s faces and bodies. When we say opening words together, we have hand motions to go with them. The children run to get food scraps and dead leaves to put into the composter; they pick up worms in their hands; they peer over a fence to look in the creek; they saw wood, hammer nails, and help hold things that other children are hammering and sawing; they pick up tools and materials and put them away.

Of course I and the other teachers explain things with words, but those words are linked to specific bodily actions: hold the hammer like this, don’t forget to put a little water in the worm composter, etc. When we talk about removing House Sparrow eggs from the nesting box, this is not an abstract discussion, we were talking about a living organism that might cause a problem that we had to face with hands and hearts.

What these sixth graders, and we adult teachers, experience in the worship service and throughout the class can be understood metaphorically as a form of dance; not high-art dance done as a performance by professionals (e.g., ballet, modern dance, etc.), but participatory social dance done as a community. Even though our congregation rarely includes dance in our formal worship services (as is true of most religious groups stemming from the Christian tradition), you can find elements of informal social dance throughout the worship service, and in the liturgical elements interspersed through the class time: a time to stand and to sit, a time to greet each other in worship; a time to run pell-mell, a time to pick up worms; gestures and movements that express who we are and how we are interconnected. If we did not have these elements of dance, if we did not respect the bodies of all those in our congregation, it is likely that the children would be much less willing to be part of our congregation: “If children are screaming, they might just be having a bad day or else they might be doing what many of the adults feel like doing.” Not that we always manage to respect the bodies of those in our congregation, but at our best, children, teens, and adults embody our values through dance-like moves.

Carla Walter, a dancer and scholar in our congregation, describes a womanist spirituality, drawing on African spirituality, which helps me understand what our post-Christian congregation aspires to. A womanist spirituality, says Walter, incorporating elements like dance, music, oral tradition, direct perception of spiritual matters, and relationships with other people, “draws on ancient knowledge of power in our spirits and communities to move us as it remembers the past, and on today’s hegemonically valued groups to work against intra- and intergroup hatred to build social sustainable structures. Spiritual wholeness is what is sought, in interconnectivity….” This is what we are trying to do with our children and teens: make socially sustainable structures, seek spiritual wholeness. Womanist spirituality, a “struggle spirituality” that was never subject to Cartesian dualism and “the Adam and Eve mythos that informs Western religion,” helps us dance through the resistance to Western religion; rather than correct interpretation of sacred texts to solve environmental problems, it nurtures spiritual wholeness and liberation through interconnectivity.

In a post-Christian congregation such as the one I serve, children, teens, and their parents are rightly wary of religion that serves imperial ambitions; rightly suspicious of Western-style religion imposing its hierarchies and standardization on us. As we move away from standardization, then contemporary poems, like the one Beverly read at the beginning of the worship service I described, may serve as sacred texts. As we move away from standardization of religion, we may listen when an elder in our congregation vigorously asserts that “you don’t get your ethics by reading, you get your ethics by living,” we may notice the persons in our congregation who are preliterate children, and we may conclude that reading sacred texts isn’t as important as it has been in Western-style religion. Our bioregion and cultural context may also influences us: here in the San Francisco Bay watershed, an urban area on the Pacific Rim with a large East Asian population, we may find ourselves understanding religion in Asian terms, in non-Western terms, as “a matter of seasonal rituals, ethical insights, and narratives handed down from generation to generation.”

As we re-imagine religious education, I find the image of the Web of Life helps to make sense out of the many and varied dance moves we engage in. Bernard Loomer, a theologian affiliated with both mainline Protestant and post-Christian congregations, described the Web of Life as “an indefinitely extended complex of interrelated, inter-dependent events or units of reality,” a complex which includes “the human and non-human, the organic and inorganic levels of life and existence”; what Jesus called the Kingdom of God was also the Web of Life, although this insight of Jesus’s was “covered over because we have surrounded Jesus with religiosity.” In the Web of Life, humans and non-humans and the inorganic are all bound together in a web of relationships; reworking more traditional Christian terms, Loomer says that sin is when we act against this web of relationships, while forgiveness “is a restoration to those relationships.” Loomer adds that as human civilization advances we create the need “for adopting disciplines that are more complex and requiring virtues beyond anything the human spirit has known.” Loomer added: “If the response is inadequate the human organism may turn out to be a dead end.”

Imagine religion as a dance which restores us to the Web of Life, rather than acting against the relationships of the Web of Life. In this dance, we are interconnected with other persons as embodied beings bound in a web of relationships. Those relationships begin in the immediate human community where we are dancing; the relationships extend further into the immediate bioregion of the local watershed; and then still further into the relationships of the whole of the Web of Life. The relationships in the Web of Life are not neat and tidy; rather the Web of Life is a thicket and bramble wilderness filled with the messiness of becoming. In this dance, we communicate the reality of the Web of Life through gestures rather than through words or texts, through the interaction of the whole selves of embodied human beings.

A scholar of religion who walked into one of our classes and saw a bunch of sixth graders building birdhouses might be forgiven for thinking this class didn’t involve religion. Where are the texts, the beliefs, the prayers that define U.S. religiosity? Yet our post-Christian faith community might also be forgiven for thinking that organized religion has, so far, not been very effective in dealing with environmental crisis. It may not look like it on the surface, but our children and teens are dancing their way towards socially sustainable structures of spiritual wholeness. The poet Marge Piercy says:

Connections are made slowly, sometimes they grow underground.

You cannot tell always by looking what is happening.