Greek Myths v. 1.0

A curriculum for upper elementary grades

Copyright notice:

Curriculum copyright (c) 2014 Dan Harper and Tessa Swartz

Lesson plans (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

Introduction copyright (c) 2015-2024 Dan Harper

Stories marked individually for copyright

Illustrations individually marked for copyright status

Back to the Table of Contents | On to Session Eight

This lesson plan contains two stories: the story of the Sphinx, and the story of Theseus and the Minotaur. Eventually, this lesson plan will be divided into two separate lesson plans. In the mean time, you’ll find enough here to fill two separate session.

THE SPHINX

Laius, king of Thebes, was warned by an oracle that there was danger to his throne and life if his new-born son should be suffered to grow up. He therefore committed the child to the care of a herdsman with orders to destroy him; but the herdsman, moved with pity, yet not daring entirely to disobey, tied up the child by the feet and left him hanging to the branch of a tree. In this condition the infant was found by a peasant, who carried him to his master and mistress, by whom he was adopted and called Oedipus, or Swollen-foot.

Many years afterwards, Laius, who was on his way to Delphi, accompanied only by one attendant, met in a narrow road a young man also driving in a chariot. On his refusal to leave the road at their command, the attendant killed one of his horses, and the stranger, filled with rage, slew both Laius and his attendant. The young man was Oedipus, who thus unknowingly became the slayer of his own father.

Shortly after this event, the city of Thebes was afflicted with a monster which infested the highroad. She was called the Sphinx. She was the daughter of the monsters Ekhidna and Typhon. She had the body of a lion and the upper part of a woman. She lay crouched on the top of a rock, and stopped all travelers who came that way proposing to them a riddle, with the condition that those who could solve it should pass safe, but those who failed should be killed. Not one had yet succeeded in solving it, and all had been slain.

Oedipus was not daunted by these alarming accounts, but boldly advanced to the trial.

The Sphinx asked him, “What animal is that which in the morning goes on four feet, at noon on two, and in the evening upon three?”

Oedipus replied, “A human being, who in childhood creeps on hands and knees, in adulthood walks erect, and in old age goes about with the aid of a cane.”

The Sphinx was so mortified at the solving of her riddle that she cast herself down from the rock and perished.

The gratitude of the people for their deliverance was so great that they made Oedipus their king, giving him in marriage their queen Jocasta. Oedipus, ignorant of his parentage, had already become the slayer of his father; in marrying the queen he became the husband of his mother. These horrors remained undiscovered, till at length Thebes was afflicted with famine and pestilence, and the oracle being consulted, the double crime of Oedipus came to light. Jocasta put an end to her own life, and Oedipus, seized with madness, tore out his eyes and wandered away from Thebes, dreaded and abandoned by all except his daughters, who faithfully adhered to him, till after a tedious period of miserable wandering he found the termination of his wretched life.

Source: We adapted this story from Bulfinch’s mythology: The age of fable, The age of chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne, rev. ed., by Thomas Bulfinch (New York: T. Y. Crowell Co., 1913), chapter XVI, “Monsters: Giants — Sphinx — Pegasus and Chimaera — Centaurs — Griffin — Pygmies.” Public domain story.

Pronunciation guide:

Laius — LAY us

Thebes — THEEBS

Oedipus — ED i puss

Sphinx — SFINX

Ekhidna — eh KID nah

Typhon — TIE fon

UNIT TWO: MONSTERS

Session Seven: The Sphinx

Materials

Optional: Pages of sphinx shapes for cutting out (see below)

Optional: Scissors

Optional: Print out finger labyrinth sheets (see below)

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story “The Sphinx”

Read the story above.

III/ Act out the story

There are only a few major characters (Oedipus and the Sphinx and Laius), but with lots of minor characters this is another great story to act out!

Ask the children who are the characters in the story, and perhaps have someone (you or one of the children) write them down. Ask who wants to act out the different parts (and note that you don’t have to be the same gender as the part you’d like to act out).

Get ready to act out the story. Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with you; you will sit facing the stage.

IV/ Ancient Greek riddles

Riddles and puzzles have been an important part of Western culture since early times. Many early cultures in the Ancient Near East used riddles. In one well-known example, the Hebrew Bible contains a riddle in the story of Samson (Judges 12:1-14). This Bible riddle doesn’t seem to have any purpose aside from helping move the plot of the story forward. That is probably true of many riddles in traditional cultures — sometimes a good riddle is just a good riddle, with no deeper meaning.

On the other hand, sometimes there are puzzling statements which do have a deeper meaning. The ancient Greek collection of poetry called The Palantine Anthology contains both riddles and oracles. An oracle was a statement attributed to a god or goddess. It was considered extremely important to interpret the oracle correctly. Interpreting the oracle incorrectly could lead to dire consequences. (See the answer to Riddle 2 below for an example of an oracle.)

The Sphinx’s riddles probably lie somewhere between these two extremes. They don’t have the importance of an oracle given by the gods and goddesses. Yet Theseus knew he had to answer the Sphinx’s riddles correctly, at the risk of his life.

With the above background in mind, you can say something like this to the children:

“Today we tend to think that riddles are supposed to be funny, but in ancient Greek times, riddles were puzzles that made you think, like the riddle of the Sphinx. The riddle of the Sphinx is both a good puzzle, and it is something that makes you think about the world in a new way. The Sphinx had a second riddle, which goes like this: ‘There are two sisters: one gives birth to the other and she, in turn, gives birth to the first. Who are the two sisters? Can you answer this riddle?” Answer is given below.

Below are fifteen ancient Greek riddles to share with the children. Some of these are easy to guess, some are difficult. Some may require knowledge that the children may not have. Let the children know that they may not be able to come up with the answers to all these riddles. Answers are given below.

In fact, for some of these riddles, the original answer has been lost. For these riddles, can the class come up with an answer that all the children feel is correct?

1

From a bright father my being springs,

I soar aloft, but not with wings —

Tears, without sorrow, to your eye

I draw; and, scarcely born, I die.

2

The poet Homer supposedly died from frustration because he could not answer this riddle, put to him by some children:

What we caught we left; what we did not catch we have brought.

3

My mother I bring forth, she brings forth me:

I’m sometimes greater, sometimes less than she.

4

I look at you whenever you look at me;

You see but I see not; no sight have I;

I speak but have no voice; your voice is heard;

My lips can only open uselessly.

5

There are two sisters; one gives birth to the other, and herself having brought forth is born from the other, so that being sisters and of the same family they are actually sisters and mothers in common.

6

Speak not and you shall speak my name. But must you speak?

Then again, a great wonder, because by speaking you shall speak my name.

7

My father is a ram, and a tortoise bore me to him, and at my birth I killed both my parents.

8

If one call me an island, he shall tell no falsehood for of a truth have gave my name to many noises.

9

Because of the light I lost my light, but a man standing by me gave me a clear light, doing a kindness to his feet.

10

I have a brain without a head, and I am green and rise from the earth by a long neck. I am like a ball placed on a flute, I have there my mother’s father.

11

There is one father and twelve children. Each of these has thirty children of different appearance; some of them we see to be white and others black, and though immortal, they all perish.

12

If you had taken me in my youth, you would have happily drunk the blood shed from me; but now that time has finished making me old, eat me, wrinkled as I am, with no moisture in me, crushing my bones together with my flesh.

13

I have nothing inside me and everything inside me. I give the use of myself to anyone without charge.

14

No one sees me when they see. But they see me when they see not. They who speak not speak, and they who run not run, and I am untruthful though I tell all truth.

15

(This last riddle should be easy for the class to guess.)

A creeping, flying, walking maiden; a lioness lifting up feet not her own as she ran; she was a woman winged in front, in the middle a roaring lioness, and behind a curling snake. She ran away neither making a trail nor as a woman, nor either bird or beast in her whole body; for she seemed to be a maiden without feet, and the roaring beast had no head.

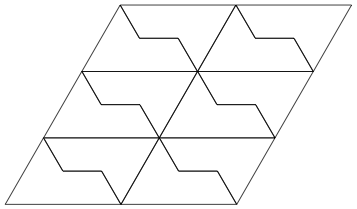

V/ Making the Sphinx puzzle

This is a fun puzzle called “The Sphinx,” although it was not invented in ancient Greece. Even though it really has nothing to do with ancient Greece, children have found it to be lots of fun. The puzzle also shows how ancient Greek myths remain important in our Western culture — calling this puzzle the Sphinx is a way of saying that it’s kind of myseterious and puzzling.

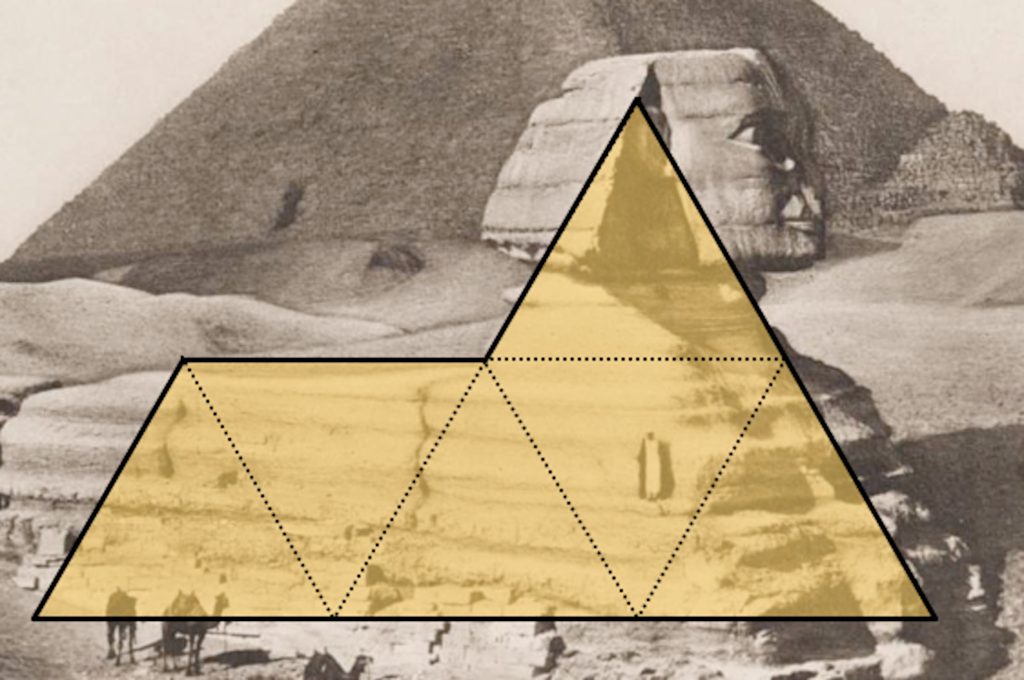

The “sphinx” of this puzzle is a five-sided figure, made up of six equilateral triangles. This five-sided shape is called a “sphinx” because it looks a little like the giant Sphinx at Giza in Egypt. Here’s the sphinx shape superimposed on a photo of the Sphinx at Giza:

(Here’s an interesting factoid: the ancient Greeks traced the origins of their Sphinx back to Egyptian Sphinxes. However, as you can see above, Egyptian Sphinxes did not have wings — unlike Greek Sphinxes, which did have wings.)

Before we get to the puzzle, you’ll need some sphinx shapes for your children to work with. Click here for a PDF of sphinx shapes for cutting out. Print 1 sheet of sphinx shapes for every child in your group.

(1) Split the children into pairs, and give each pair at least two sheets of sphinx shapes for cutting out (the PDF above). Have them cut out four of the sphinx shapes. Now, using 4 sphinx shapes, make 1 large sphinx shape. This is called a Size 2 Sphinx.

Some pairs will solve this problem quickly. If they do, rather than let them tell other children how to solve the problem, give the the next puzzle:

(2) Cut out a total of 16 sphinx shapes. Now make Size 4 Sphinx. (If you think about it for a moment, you should see an easy way to do this.)

(3) If some members of your group handle the first two puzzles quickly, you can challenge them to make a Size 3 Sphinx.

Ten minutes will be plenty of time to spend on this activity. To wrap up the activity, you could ask the children to imagine what would have happened if the Sphinx had challenged Oedipus with the sphinx shapes. Would he have been smart enough to solve one of these puzzles? Is this challenge more difficult than the riddle of the Sphinx? Why or why not? (Note that different people will have different answers to these questions.)

(Some children may want to keep working with sphinx shapes. You can find more sphinx shapes puzzles at the Mathematics Centre of Australia.)

VI/ Optional added activity: The Minotaur and labyrinths

N.B.: This section will eventually be separated out into its own lesson plan.

Some groups of children may not be interested in either riddles or puzzles. If that is true of your class, then you can use this optional section on labyrinths.

To begin, you can tell the story of Theseus and the Minotaur, in which a labyrinth plays a key part (see Leader Resource #1).

After reading the story, you can tell the children that labyrinths are still used today — not to keep a monster in place, but as a form of meditation. Labyrinths have been a part of Western culture since the time of the ancient Greeks. The medieval Christians included labyrinths in their great cathedrals, most famously in the cathedral building at Chartres; for these Christians, the twisting and turning of the labyrinth represented the spiritual challenges of the journey of life. Europeans who were not Christians had their own spiritual tradition of labyrinths. Still today Pagans, Christians, and nonbelievers use walking a labyrinth as a kind of meditation.

If you have access to a walkable labyrinth (like the one in the photo below), you could take your class to walk that labyrinth. Tell the children that walking a labyrinth can both be fun meditative. You could even could walk the labyrinth twice — once as a form of meditation, and the second time to re-enact the story of Theseus and the Minotaur.

If you don’t have access to a full-size labyrinth, you can also use finger labyrinths. To use a finger labyrinth, print out one of the labyrinths below onto a sheet of paper, then use your finger to trace the path from the outside to the center, and back again. It takes real concentration to do it without losing your place, crossing over lines, or lifting your finger! (Using a pencil to trace your route is considered cheating for a finger labyrinth.) While the children are following their labyrinths, you could tell the story of Theseus and the Minotaur that’s in Leader Resource #2.

In addition to the finger labyrinths, you might want to show the children a maze. The difference between a maze and a labyrinth is simple: a labyrinth has only one path in and out, while a maze is a puzzle with multiple paths.

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What happened in the story we heard today? What did Demeter do, and why? etc.” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

End by saying together some closing words, perhaps something like these:

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

Then before you all go, tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (assuming that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

LEADER RESOURCES

1. The story of the Minotaur

Here’s the story of the Minotaur, taken from Bulfinch’s Mythology:

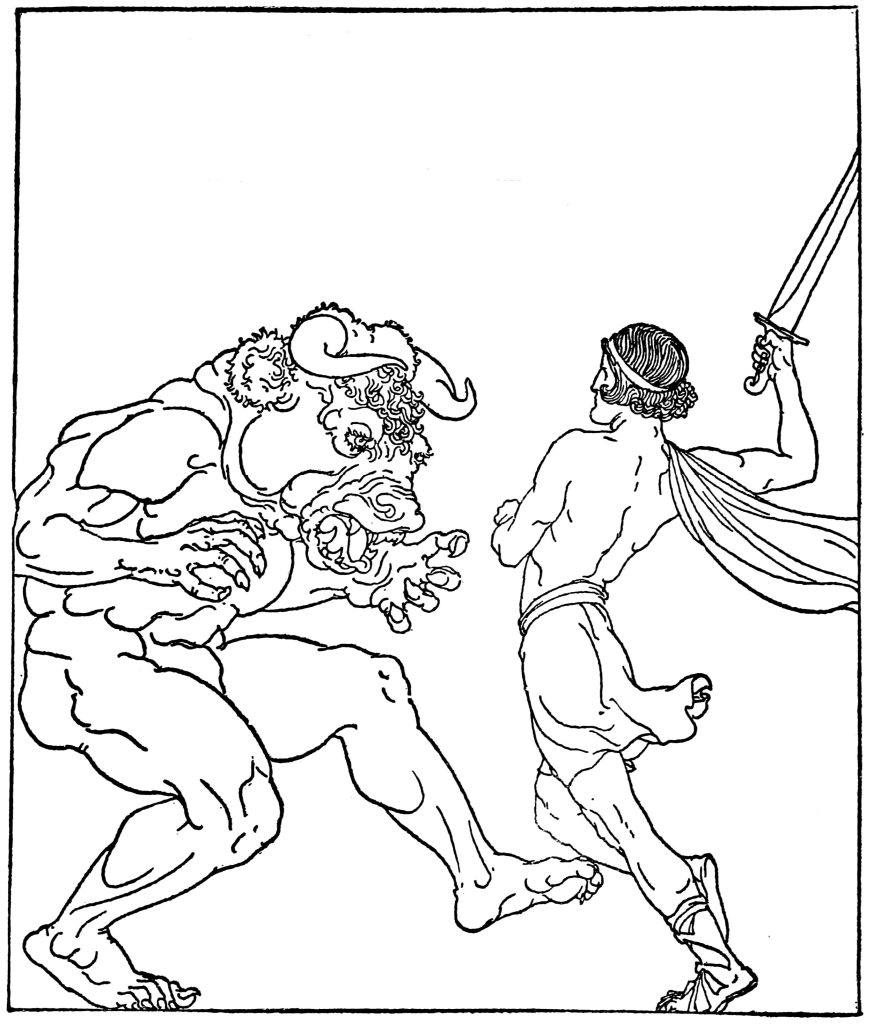

“The Athenians were at that time in deep affliction, on account of the tribute which they were forced to pay to Minos, king of Crete. This tribute consisted of seven youths and seven maidens, who were sent every year to be devoured by the Minotaur, a monster with a bull’s body and a human head. It was exceedingly strong and fierce, and was kept in a labyrinth constructed by Daedalus, so artfully contrived that whoever was enclosed in it could by no means find his way out unassisted. Here the Minotaur roamed, and was fed with human victims.

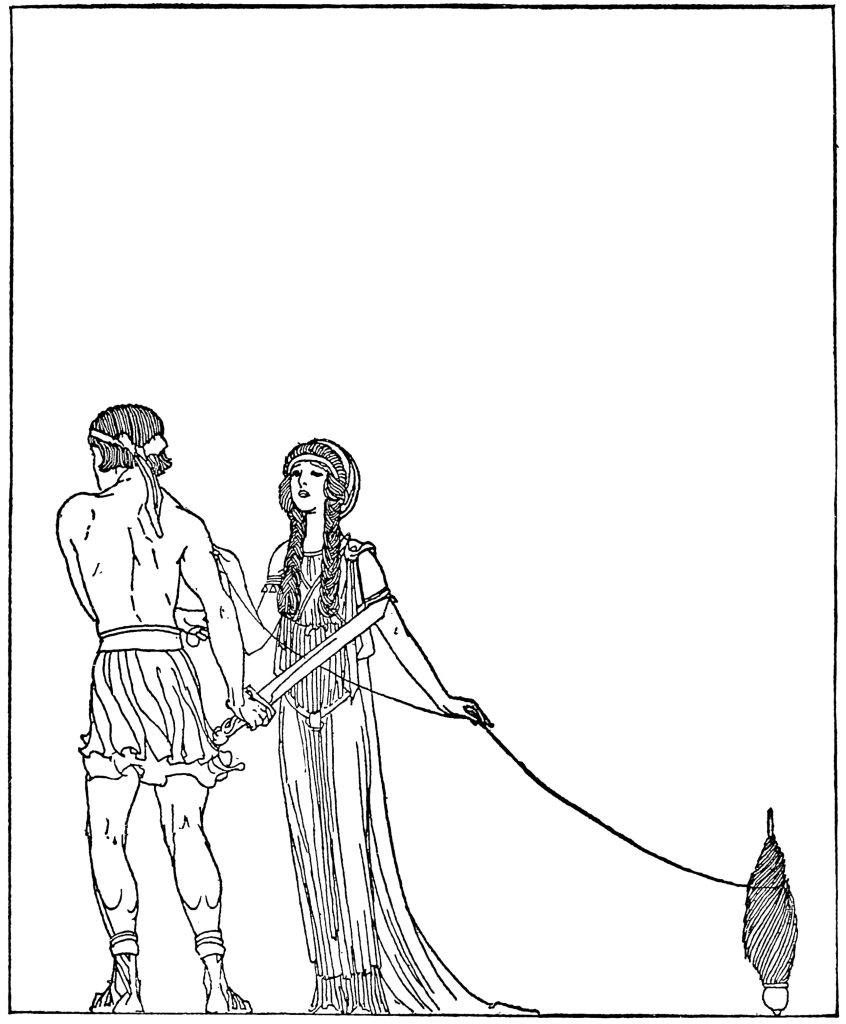

“Theseus resolved to deliver his countrymen from this calamity, or to die in attempt. Accordingly, when the time of sending off the tribute came, and the youths and maidens were, according to custom, drawn by lot to be sent, he offered himself as one of the victims, in spite of the entreaties of his father. The ship departed under black sails, as usual, which Theseus promised his father to change for white, in case of his returning victorious. When they arrived in Crete, the youths and maidens were exhibited before Minos, and Ariadne, the daughter of the king, being present, became deeply enamored of Theseus, by whom her love was readily returned.

“She furnished him with a sword, with which to encounter the Minotaur, and with a clew of thread by which he might find his way out of the labyrinth. He was successful, slew the Minotaur, escaped from the labyrinth, and taking Ariadne as the companion of his way, with his rescued companions sailed for Athens. On their way they stopped at the island of Naxos, where Theseus abandoned Ariadne, leaving her asleep. His excuse for this ungrateful treatment of his benefactress was that Athena appeared to him in a dream and commanded him to do so.

“On approaching the coast of Attica, Theseus forgot the signal appointed by his father, and neglected to raise the white sails, and the old king, thinking his son had perished, put an end to his own life. Theseus thus became king of Athens.”

2. The source of the Sphinx story

The version of the Sphinx story used above comes from the classic retelling of myths by the 19th century American author Thomas Bulfinch. We don’t have any ancient Greek sources that tell this story exactly like this; Bulfinch pieced together his story from various Greek and Latin sources.

One of the sources Bulfinch drew on for his tale was a 2nd century BCE collection of myths known as Apollodorus, the Library. In that collection, the story of the Sphinx goes like this:

“Laius was buried by Damasistratus, king of Plataea, and Creon, son of Menoeceus, succeeded to the kingdom. In his reign a heavy calamity befell Thebes. For Hera sent the Sphinx, whose mother was Echidna and her father Typhon; and she had the face of a woman, the breast and feet and tail of a lion, and the wings of a bird. And having learned a riddle from the Muses, she sat on Mount Phicium, and propounded it to the Thebans. And the riddle was this: ‘What is that which has one voice and yet becomes four-footed and two-footed and three-footed?’

“Now the Thebans were in possession of an oracle which declared that they should be rid of the Sphinx whenever they had read her riddle; so they often met and discussed the answer, and when they could not find it the Sphinx used to snatch away one of them and gobble him up. When many had perished, and last of all Creon’s son Haemon, Creon made proclamation that to him who should read the riddle he would give both the kingdom and the wife of Laius.

“On hearing that, Oedipus found the solution, declaring that the riddle of the Sphinx referred to man; for as a babe he is four-footed, going on four limbs, as an adult he is two-footed, and as an old man he gets besides a third support in a staff. So the Sphinx threw herself from the citadel, and Oedipus both succeeded to the kingdom and unwittingly married his mother, and begat sons by her, Polynices and Eteocles, and daughters, Ismene and Antigone. But some say the children were borne to him by Eurygania, daughter of Hyperphas.” (from Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation, by Sir James George Frazer (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1921); book 3, chapter 5, section 8)

To this basic story, Bulfinch added a back story, and he also summarized the tragic ending of Oedpius’s life. Bulfinch’s tale is a good example of how people continue to retell these ancient stories more than two thousand years after they were first told. And they continue to be retold in pop culture today, e.g., in the Percy Jackson series.

3. Answers to the riddles

The answer to the Sphinx’s other riddle:

Day and night.

1

Smoke.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 5; trans. Robert Bland)

2

No one knows the answer to this ancient riddle! Since the riddle was posed by children, you’d think that it should be possible to guess it — but in the past 2,500 years, no one has guessed it. (Cited in Forster)

Ancient sources record that Homer received an oracle from the gods that went like this: “There is an island, Ios, that is the fatherland of thy mother, which shall recive thee on thy death. But beware the riddle of the young boys” (Palantine Anthology, xiv. 65; trans. Paton).

In other words, the gods warned Homer that he would die from not being able to answer a riddle posed to him by children!

3

Night and day.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 41; trans. Forster)

4

A reflection in a mirror.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 56; trans. Forster)

5

Day and night.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 40; trans. Paton)

6

Silence

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 22; trans. Paton)

7

No one knows the answer to this ancient riddle!

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 30; trans. Paton)

8

No one knows the answer to this ancient riddle!

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 39; trans. Paton)

9

A lantern.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 47; trans. Paton)

10

An artichoke (“my mother’s father” means the seed in the core of an artichoke)

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 58; trans. Paton)

11

The year, the months, and the days and nights.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 101; trans. Paton)

12

A raisin. (In ancient Greek times, there were no such thing as seedless raisins, so when you chewed a raisin you might crunch on the seeds.)

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 103; trans. Paton)

13

A mirror.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 108; trans. Paton)

14

Sleep with dreams.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 110; trans. Paton)

15

The Sphinx.

(Palantine Anthology, xiv. 63; trans. Paton)

Sources for the riddles

Robert Bland, Collections from the Greek Anthology (London, 1913).

E. S. Forster, “Riddles and Problems from the Greek Anthology” (Greece and Rome, vol. 14 no. 41/42, June 1945), pp. 42 ff.

W. R. Paton, The Greek Anthology with an English Translation, vol. 5 (London and New York: William Heinemann, 1928)