Beginnings: Myths and stories from world religions

A curriculum for upper elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2014-2022 Dan Harper

Updated 11/22

The Hymn of Purusha: A Story from India

This is just one of many Hindu stories about how everything began.

Before the beginning of all things, a giant named Purusha existed. Purusha had thousands of heads, and thousands of eyes, and thousands of feet. He was huge and embraced the earth on all sides; and at the same time he filled a space only ten fingers wide, the size of the space which holds a human soul.

The giant Purusha is everything, all that had once been, and all that which shall be in the future. He is the god of immortality, and he now lives through sacrificial food which humans offer up to him. All beings and creatures make up one quarter of him; the rest of him is immortal life in a world beyond this world. Before the beginning, the three quarters of Purusha which was immortal life rose up high, and the remaining one quarter of him remained here.

Purusha gave birth to his female counterpart, who was named Virat. When she was born, she took the form of an egg. And then Virat in turn gave birth, and she bore her male counterpart, Purusha. As soon as Virat had given birth to Purusa, he spread to the east and to the west over the earth. Together, Purusha and Virat produced the universe.

Then the Deities prepared Purusha as a sacrifice. They did not sacrifice him as humans might sacrifice an animal; it was a spsiritual sacrifice, an imaginary sacrifice. The clarified butter or ghee which they used in preparing the sacrifice was springtime. The wood which they gathered for the fire to burn the sacrifice was autumn. And the sacrifice himself, the giant Purusha, was summertime. All the Deities, and all the celestial beings, and all the sages sacrificed with him.

The ghee from the sacrifice was gathered up. Purusha, who was born in the beginning, was sprinkled on the grass. He formed the creatures of the air, and he formed the beasts of the forest and the beasts of the village. From that sacrifice were born horses, and cattle, and goats, and sheep.

And from the sacrifice were born the hymns of the Rig Veda, and the melodies of the Sama Veda. From the sacrifice came the ritual, and from it came the meters of poetry.

When Purusha was divided up after the sacrifice, his mouth became the Brahmins or the priests; his arms became the warriors and soldiers; his legs became the traders and farmers; and his feet became the workers and the slaves.

When Purusha was divided up, the Moon was born from his mind and his spirit; the Sun was born from his eye; from his mouth were born both Indra, the god of storms and warfare, and Agni, the god of fire; from his breath was born Vayu, the god of wind and of blowing breath and of life.

When Purusha was divided up, his navel became the middle sky, his head became the heavens, his feet became the earth. And so it was that all the worlds were made, and all that is began.

Sources

I drew on two translations of this hymn: Ralph T. H. Griffith, The Hymns of the Rig Veda: Translated with a Popular Commentary (1889; reprinted New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1987), vol. 2, pp. 558-561; and Edward J. thomas, Vedic Hymns, Wisdom of the East series (London: 1923), reprinted in A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy, ed. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University, 1957), pp. 19-20.

This hymn has been the subject of long and sophisticated philosophical and religious reflection. In my retelling of it, I relied heavily on Griffith’s notes, and the notes provided in Radhakrishnan and Moore, to try to provide a simple yet reasonably accurate interpretation.

Images

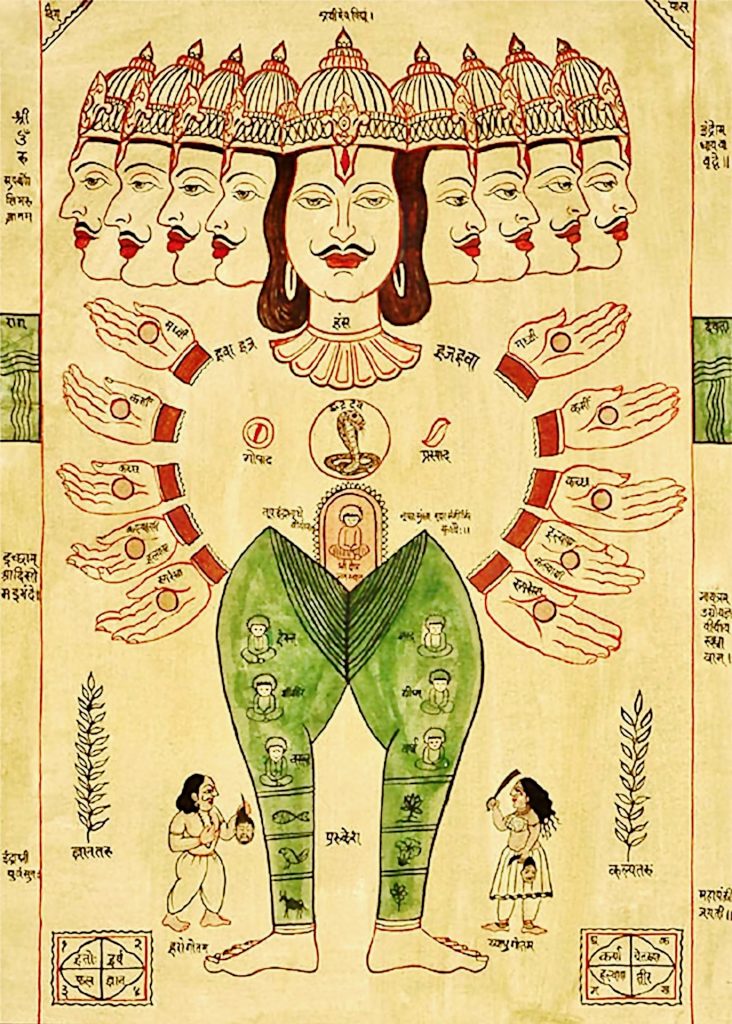

Purusha is more of a concept than a being. Thus images of Purusha may appear to be quite conceptual, as in this Tantric depiction:

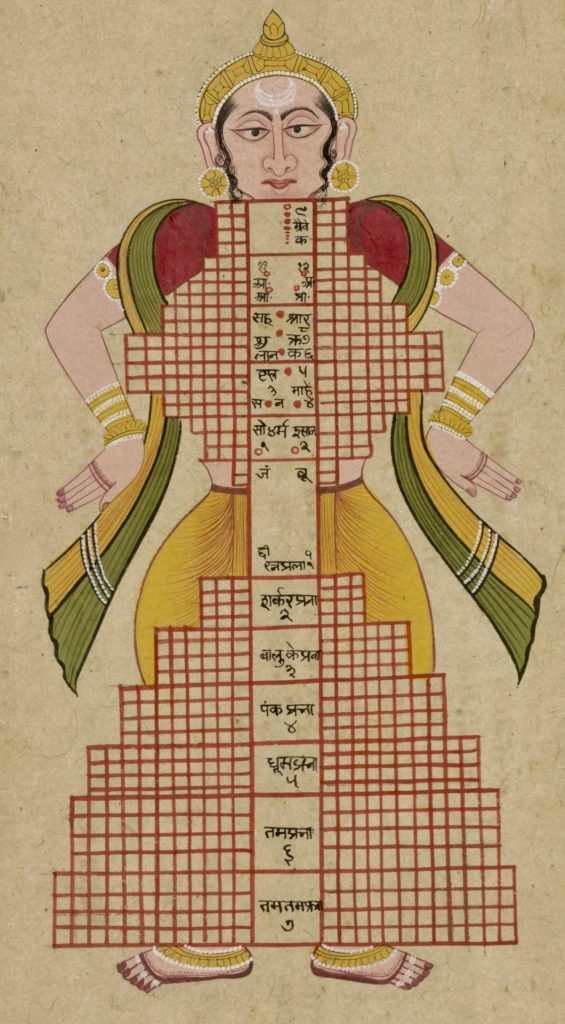

Jains also include Purusha in their cosmological concepts. In the drawing below, the three levels of Purusha’s clothing represent the three levels of the Jain cosmos, called the triloka. The Jain concept is not identical to the Hindu deity in the story above, but it is conceptually similar.

For more images, see the screen grabs from a contemporary video below.

UNIT TWO: MYTHS OF COSMIC EGGS

Session Eight: The hymn of Purusha

Attend the first part of the worship service with the rest of the congregation.

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story.

Read “The hymn of Purusha” (see above).

III/ Conversation about the story

Ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story for you? Who was your favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own. You may want to talk with the children about the similarities between this story and the story of Pangu [see session six].

IV/ Option One: Closing celebration and snack

N.B.: Use this if this is the last class of the regular Sunday school year.

Remind the children that this will be the last meeting of this Sunday school class. Tell them how much fun you’ve had being with them all year (assuming that is true).

Bring out the snack (maybe something that’s not too healthy—cupcakes, even). While you’re eating snack, look over the class bulletin board. You may wish to organize it better, or you may wish to simply look at all the drawings and photos and talk about them.

Remind the children that they can invite their parents to come look at the bulletin board after class is over. They may take home their art work when their parents come in to look at the bulletin board.

V/ Option Two: Purusha video

If you’re not doing a closing celebration, you can listen to and watch this video instead. The chanting is Mantra Pushpam, Swasti Vachakam, from “Rudram Namakam Chamakam Songs,” as sung by S. Murthy Sarma and S. Viswanadha Sastry. This song consists of stanzas from the Rig Veda that tell about Purusha.

To help the children focus on the meaning of the chant, have them help you read the English subtitles out loud — maybe take turns, if everyone’s a fluent reader. (See the Leader Resources below for a different English translation of this hymn than appears in the subtitles.)

Although the video is about seven minutes long, you’ll probably want to watch no more than three minutes — in other words, up to the creation of the animals. You may want to pause the video and look at some of the images, especially the contemporary depictions of Purusha.

For your reference, I’ve included some screen grabs from the video below, showing some of the more interesting contemporary depictions of Purusha.

Talking about the video

Above all, you want the children to notice that this is a contemporary version of an ancient religious hymn. People still take Purusha seriously enough to make devotional videos. Note some of the comments on this Youtube video: “The Chanting transforms as Elixir that falls into the ear as well as into the soul” — “An awesome video explaining the cosmos as a manifestation of the Supreme. Thank you so much…. Hari Om.”

Now talk about the children’s reactions to this video (and your own reactions, if appropriate). Probably some of the children will not enjoy this music. You should tell them that that is fine, because for people who don’t know much about music and chanting of the Indians subcontinent, this music may seem strange or even unpleasant at first. Other children may find this music relaxing and/or enjoyable.

We frequently talk about mindfulness with children these days, but not every child finds mindfulness practice useful. So you might tell the children that there are some people who have a hard time sitting still and being mindful, but who find listening to chanting like this provides much the same benefits — reduced stress, relaxation, etc.

Some open-ended questions on the video:

What did you think of the images of Purusha?

What did you think of the music?

What did you think of the poetry?

V/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

When you’ve reviewed what the children learned for a couple of minutes, say together the unison benediction (which is posted in your classroom). Tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

Leader resources

I/ Caste in the Rig Veda hymn

This hymn is of interest because it is the only mention of the four traditional Hindu castes to be found in the Rig Veda, in verse 12. For that reason alone, it is worth introducing to liberal religious kids as part of their religious literacy.

Regarding the four castes, Griffith writes the following in his note for verse 12:

“…The Brahman is called the mouth of Purusha, as having the special privilege, as a priest, of addressing the Gods in prayer. The arms of Purusha became the Rajanya, the prince and soldier who wields the sword and spear. His thighs, the strongest parts of his body, became the agriculturalist and tradesman, the chief support of society; and his feet, the emblem of vigour and activity, became the Sudra or labouring man on whose toil and industry all ultimately rests. This is the only passage in the Rgveda which enumerates the four castes.”

In her recent book The Hindus: An Alternative History (New York: Penguid, 2009), Wendy Doniger offers the following useful analysis of this hymn:

“…A poem in one of the latest books of the Rig Veda, “Poem of the Primeval Man” (Purusha-Sukta [10.90]), is about the dismemberment of the cosmic giant, the Primeval Man (purusha later comes to designate any male creature, indeed, the male gender), who is the victim in a Vedic sacrifice that creates the whole universe. The poem says, “The gods, performing the sacrifice, bound the Man as the sacrificial beast. With the sacrifice the gods sacrificed to the sacrifice.” Here the “sacrifice” designates both the tirual and the victim killed in the ritual; moreover, the Man is both the victim that the gods sacrificed and the divinity to whom the sacrifice was dedicated — that is, he is both the subject and the object of the sacrifice. This Vedic chicken or egg paradox is repeated [elsewhere in Vedic thought]…. But it is also a tautological way of thinking that we … continue to encounter in Hindu mythology.” [p. 117]

Thus, in this story, Purusha and Vitaj create each other; the gods sacrifice Purusha to Purusha, and from Purusha comes all that is, including human beings in the four castes. School aged children delight in this sort of chicken and egg paradox, making this a wonderful story for them to hear and discuss.

Griffith notes parallels between the story in this creation story, and the creation story of Old Norse mythology, in which the giant Ymir is made into the world: “The hills are his bones, the vault of sky his skull, the sea his blood, and the clouds his brains.” There’s a retelling of the Ymir creation story in the old Unitarian Universalist textbook Beginnings: Earth, Sky, Life, Death by Sophia Lyon Fahs and Dorothy T. Spoerl (Boston: Beacon, 1958), and it would be fun to juxtapose Purusha and Ymir, perhaps in successive lessons.

II/ Griffith’s translation of the hymn to Purusha

For reference, below are excerpts from Griffith’s translation of the hymn, with excerpts from his footnotes:

A thousand heads hath Purusha, a thousand eyes, a thousand feet. (1)

On every side pervading earth he fills a space ten fingers wide. (2)

This Purusha is all that yet hath been and all that is to be;

The Lord of Immortality which waxes greater still by food. (3)

So mighty is his greatness; yea, greater than this is Purusha.

All creatures are one-fourth of him, three-fourths eternal life in heaven. (4)

With three-fourths Purusha went up: one-fourth of him again was here.

Thence he strode out to every side over what eats not and what eats. (5)

From him Viraj was born; again Purusha from Viraj was born.

As soon as he was born he spread eastward and westward o’er the earth.

When Gods prepared the sacrifice with Purusha as their offering,

Its oil was spring, the holy gift was autumn; summer was the wood….

From that great general sacrifice the dripping fat was gathered up. (6)

He (7) formed the creatures of the air, and animals both wild and tame….

From it were horses born, from it all cattle with two rows of teeth;

From it were generated kine, from it the goats and sheep were born.

When they divided Purusha how many portions did they make?

What do they call his mouth, his arms? What do they call his thighs and feet?

The Brahman was his mouth, of both his arms was the Rajanya made.

His thighs became the Vaisya, from his feet the Sudra was produced. (8)

The Moon was gendered from his mind, and from his eye the Sun had birth;

Indra and Agni from his mouth were born, and Vayu from his breath.

Forth from his navel came mid-air; the sky was fashioned from his head;

Earth from his feet; and from his car the regions. Thus they formed the worlds….

(1) Purusha, embodied spirit, of Man [sic; humanity] personified and regarded as the soul and original source of the universe, the personal and life-giving principle in all animated beings, is said to have a thousand, that is, innumerable, heads, eyes, and feet, as being one with all created life.

(2) A space ten fingers wide: the region of the heart of a man [sic; human being], wherein the soul was supposed to reside. Although as the Universal Soul he pervades the universe, as the Individual Soul he is enclosed in a space of narrow dimensions.

(3) The meaning of the words seems to be: he is lord of immortality or the immortal world of the Gods, which grows greater by food, that is, by the sacrificial offereings of men [sic; human beings]….

(4) Eternal life : amritam : immortality, or the immortal Gods.

(5) Over what eats not and what eats: over animate and inanimate creation….

(6) The dripping fat: ‘The mixture of curds and butter.’

(7) He: or, it; the sacrificed victim Purusha, or the sacred clarified butter.

(8) Rajyana: the second or Kshatriya caste, the regal and military class. Vaisya: the husbandman [sic[; he whose business is agriculture and trade. Sudra: the laborer. The Brahman is called the mouth of Purusha, as having the special privilege, as a priest, of addressing the Gods in prayer. The arms of Purusha become the Rajanya, the prince and soldier who weilds the sword and spear. His thighs, the strongest parts of his body, became the agriculturist and tradesman, the chief supporter of society; and his feet, the emblem of vigor and activity, became the Sudra or laboring man on whose toil and industry all ultimately rests. This is the only passage in the Rig Veda which enumerates the four castes.