A Manual for Sunday School Teachers in Unitarian Universalist Congregations

by Dan Harper, v. 1.1

Copyright (c) 2018-2025 Dan Harper

THIS PAGE IS SLATED FOR MAJOR REVISION.

Be warned — Some sections may be incompletely revised.

Important note: The photographs on this page have been carefully cropped and/or altered so no child or teen is recognizable. All the photographs in this manual are from actual religious education programs at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto, 2012-2018.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Goals and Visions

1-A. The principles and mission of the congregation

1-B. Four Big Learning Goals

1-C. What does a Sunday school teacher do?

Chapter 2: Basics of Teaching

2-A. Setting the stage

2-B. The opening circle

2-C. Using your curriculum book

2-D. The closing circle

2-E. Back-up or sponge activities

2-F. Classroom management

Chapter 3: Models of teaching and learning

3-A. Developmental stage theories

3-B. Learning styles and multiple intelligences

3-C. The traditional three-way learning styles model

3-D. How to use games, songs, movement, and more

3-E. Is it school, or something else?

Chapter 4: Procedures and policies

4-A. Substitutes

4-B. Supplies and equipment

4-C. Behavior and discipline

4-D. Child and youth protection

4-E. Emergency and health procedures

Chapter 1: Goals and Visions

What is our purpose in teaching? If you, as a teacher, know what your purpose is, it makes everything go more smoothly.

1-A. Principles of Unitarian Universalism

Sunday school teachers will find it worth their while to read through the UUA Principles and Purposes, as a reminder of the stated purposes of Unitarian Universalism in the United States.

congregational missions

Sunday school teachers should be familiar with their congregation’s mission statement (if any).

Other statements of UU principles

Many Unitarian Universalist Sunday school teachers like to quote the short poem by the Universalist poet Edwin Markham:

He drew a circle that shut me out —

Heretic, rebel, a thing to flout.

But Love and I had the wit to win:

We drew a circle that took him in.

As teachers, we are always trying to draw the circle of teaching large enough to take in all the children or teens who are present.

1-B. Four Big Learning Goals

Most Unitarian Universalist congregations will find they’re aligned with the following four learning goals.

(1) We want children and teens (and adults) to have fun and feel they are part of a community.

Fun is an important part of this first goal. Sunday school is an optional activity, and if Sunday school isn’t fun, children and teens will not bother to show up.

The other part of this goal is to make children feel that they are a valued part of a community. Why is this important? The Search Institute, has developed the Developmental Assets framework, a list of 40 “supports and strengths” that children and teens need in order to thrive and succeed. Many of the Developmental Assets can be met by participating in a supportive community like our congregation.

How we achieve this goal: Opening and closing circles in Sunday school; allowing time for fun and games; overnights; etc.

How to measure progress towards this goal: Track attendance as a percentage of enrollment. 50% attendance is average; 70% attendance is excellent.

(2) We want children to gain the basic religious literacy expected in our society.

Our world has become increasingly multicultural. Part of that increased diversity is religious diversity. In most major metropolitan areas in the United States, you’ll find nearly every major world religion represented in local faith communities. Not only that, but most major metropolitan areas will have representatives including most of the wild diversity of Christianity, going well beyond Protestant and Catholics faith communities, into groups like Coptic Christians, Ethiopian Orthodox, etc. By helping our children and teens understand all this religious diversity, we can help them become better citizens. In short, we can introduce them to different faith communities, and teach them how to be tolerant of those who are different from them.

How to achieve this goal: Many of of the educational programs on this website are specifically designed to foster religious literacy, by introducing children and teens to other faith communities.

How to measure progress towards this goal: We can list the different faith communities children and teens have been introduced to; and in conversations with children and teens we can get a sense of the degree to which we have fostered tolerance.

(3) We want children to learn the skills associated with liberal religion, things such as public speaking, singing, basic leadership skills, interpersonal skills, etc.

Our Unitarian Universalist tradition has always valued lay leadership, and so we place a high value on helping children and teens develop the skills they need to run our congregations, and equally importantly to participate in running other non-profit organizations that help make the world a better place. In addition, we also place high value on lay leadership in our worship services, and so we want our children and teens to have basic public speaking and singing skills that allow them to plan and lead effective worship services.

How to achieve this goal: Regular participation in the first 15 minutes of the worship service gives children experience with group singing; all Sunday school classes foster interpersonal skills through activities like listening to other during check-in, etc.; participation in the Coming of Age program specifically trains teens for public speaking (through presenting their “credos” in a worship service); and so on.

How to measure progress towards this goal: Observing to see if children are singing along with the hymns in the worship service; observing to see how children and teens interact with each other; observing public speaking skills in theComing of ge service; etc.

(4) We aim to prepare children to become Unitarian Universalist adults, should they choose to become Unitarian Universalists when they are old enough to make their own decisions.

As Unitarian Universalist adults, we are engaged in a lifelong search for truth and goodness. We want to prepare our children and teens to join us on that search, when they become adults. To that end, we help children to become sensitive, moral, and joyful people, people who have intellectual integrity and spiritual insight.

How to achieve this goal: Children and teens learn about this by living their religion and by spending time with appropriate adult role models; the Coming of Age program specifically addresses this goal.

How to measure progress towards this goal: We typically measure this goal when teens go through the Coming of Age program.

1-C. What does a volunteer teacher do?

(1) Time commitment: Ask the person who supervises your volunteer position what the time commitment is.

Note that some teaching assignments, like the Our Whole Lives (OWL) sexuality education curriculums, may require more time — more preparation time, time to attend a training, etc.

(2) Lead Teacher: With two teachers in each classroom, usually one person takes on the responsibility for being the Lead Teacher. The Lead Teacher is the one who prepares for the day’s activities — on average, that preparation takes about an hour. (Some curriculums, like the Our Whole Lives curriculums, may require more than an hour of preparation for each class; some curriculums, like From Long Ago, are designed to require less than 30 minutes of preparation.) On the weeks that you are Lead Teacher, you can expect to spend about 2 hours — an hour on preparation, and an hour on Sunday morning setting up and teaching.

(3) Assistant Teacher: On the weeks when you are not Lead Teacher, you’re the Assistant Teacher. The Assistant Teacher helps the Lead Teacher with any set-up that may be required. When the children are present, the Assistant Teacher usually takes attendance, passes out any supplies to the children or teens, provides one-on-one help with any child who needs it, and helps with classroom management.

(4) Support and Accountability:

(5) Specific Sunday school teacher responsibilities:

a. Sunday school teachers help children and teens feel that they are a part of the congregation.

b. Sunday school teachers help meet children, teens, and their parents meet educational goals through classes and curriculum resources.

c. Sunday school teachers help keep children and teens safe (per our congregation’s Safety Policy).

d. Sunday school teachers pursue their own personal spiritual growth, allowing the teaching experience to transform them, as they in turn transform the world through their teaching.

e. Sunday school teachers have fun!

Volunteers who work with legal minors (i.e., persons under the age of 18) must receive annual safety training. As part of safety training, our congregation requires annual background checks of volunteers who work with legal minors.

Chapter 2: Basics of Teaching

THIS SECTION HAS NOT BEEN FULLY REVISED.

When you sign up to teach, you’ll receive copies of the curriculum books for you to borrow for the school year.

Yes, you may diverge from this curriculum plan to accommodate the interests of their class. However, if you choose a different lesson, or if you create your own lesson, make sure that you don’t cover material that has already been covered, or will be covered this year or next.

If you want to plan your own lesson, or if you want to learn more about how a lesson is structured, here’s a blank session plan form for you to use as you’re planning your session. And the following information will help you better understand how to plan your lesson, even if you use lessons straight out of your curriculum book.

2-A. Setting the stage

Every Sunday, adults and children join together for the first fifteen minutes of the worship service. Sunday school participants leave during the last verse of the first hymn. After leaving the service, the children and teens go to their assigned rooms.

It may take children and teens a few minutes to get to the classroom. Use those few minutes to set the stage for the rest of the session, and you’ll find that the rest of the class goes more smoothly.

How can you “set the stage”? Here are some ideas:

— Have some interesting objects on a table in the center of the room, to spark the curiosity of the children or teens. For example, when I was teaching a session of Ecojustice class, I put out lengths of redwood four-by-fours, an old-fashioned bit brace (drill) and other tools, and books about bees. As the middle schoolers came in to class, they asked what the wood was for, they wanted to know what the tools were, and they could see the book about bees. By the time I introduced the topic of the class — making bee houses for native pollinators that lay their eggs in cavities in wood — the middle schoolers were already interested and engaged in the topic.

— Have a game to play that can easily incorporate newcomers. For example, on the first day of a new Sunday school year, I like to play getting-to-know-you games, so we can all learn each others’ names. I’ll start a game like “Friends and Neighbors” (see the online game resource for rules), which can include more players as they arrive, even before opening circle to engage everyone right away.

— Get the people who arrive first to help you prepare. For example, if we’re going to be doing an art project, I’ll ask early arrivals to help me set out the materials — this gets them interested in the project before it even starts.

— Have interesting question or topic to start a conversation. For example, if the session is going to focus on the Biblical character of Noah, I might ask children, “Could Noah’s ark really have happened? Why or why not?”

— You might start a conversation, not about the topic of the day, but about them. Middle schoolers especially may be focused on their social networks and schools, and I enjoy hearing them talk about these aspects of their lives. But elementary children, too, may open up about their lives. This strategy works best when you have gotten to know a class fairly well.

Some other ideas:

— Sing a song together

— Play a recording (audio or video)

— Have a puzzle or mystery to solve

Above all, the Lead and/or the Assistant Teacher should GREET EACH CHILD OR TEEN as they come in. Let each one know that they are valued and welcomed!

(This section was inspired by a short essay written c. 1980 by Ann Fields.)

2-B. The opening circle

Every class should begin with and opening circle. An opening circle has at least three elements:

1. Taking attendance

2. Lighting the flaming chalice

3. Time for check-in or sharing

4. You might also include one of the following:

— A short reading, perhaps a poem or reading from one of the world’s scriptures that is relevant to the day’s topic

— Singing together

Leading an opening circle

First, here’s why the opening circle is so important:

The opening circle is particularly important because it provides a regular age-appropriate worship experience for children. It’s obvious that lighting the flaming chalice is a worship experience. Check-in is similar to “Caring and Sharing” or “Joys and Sorrows” in an adult service. Readings and songs can also contribute to a worship experience.

Check-in is a critical part of the opening circle. It’s particularly important because it gives every child a chance to be heard. Statistics show that even in the most enlightened classrooms, girls are not given as much time to be heard as are boys. Similarly, check-in gives members of historically marginalized groups an equal opportunity to be heard.

The opening circle can help with classroom management. As a calming worship experience, it can calm children down after their mad dash to get to the classroom; calm children tend to be better-behaved children. In addition, important personal concerns brought up during check-in can help teachers understand weekly changes in behavior.

Finally, the opening circle helps a class achieve one of the four big learning goals: making children feel they are a part of a community.

Now, here’s how to run an opening circle:

Sit in a circle, so you can all see and hear each other. Place the flaming chalice (or a simple candle) in the middle of the circle.

1. Take attendance

Taking attendance is a way to repeat everyone’s name once again, plus you get the names of any new children. (And in case of an emergency evacuation, you have a record of who is present).

2. Light the flaming chalice

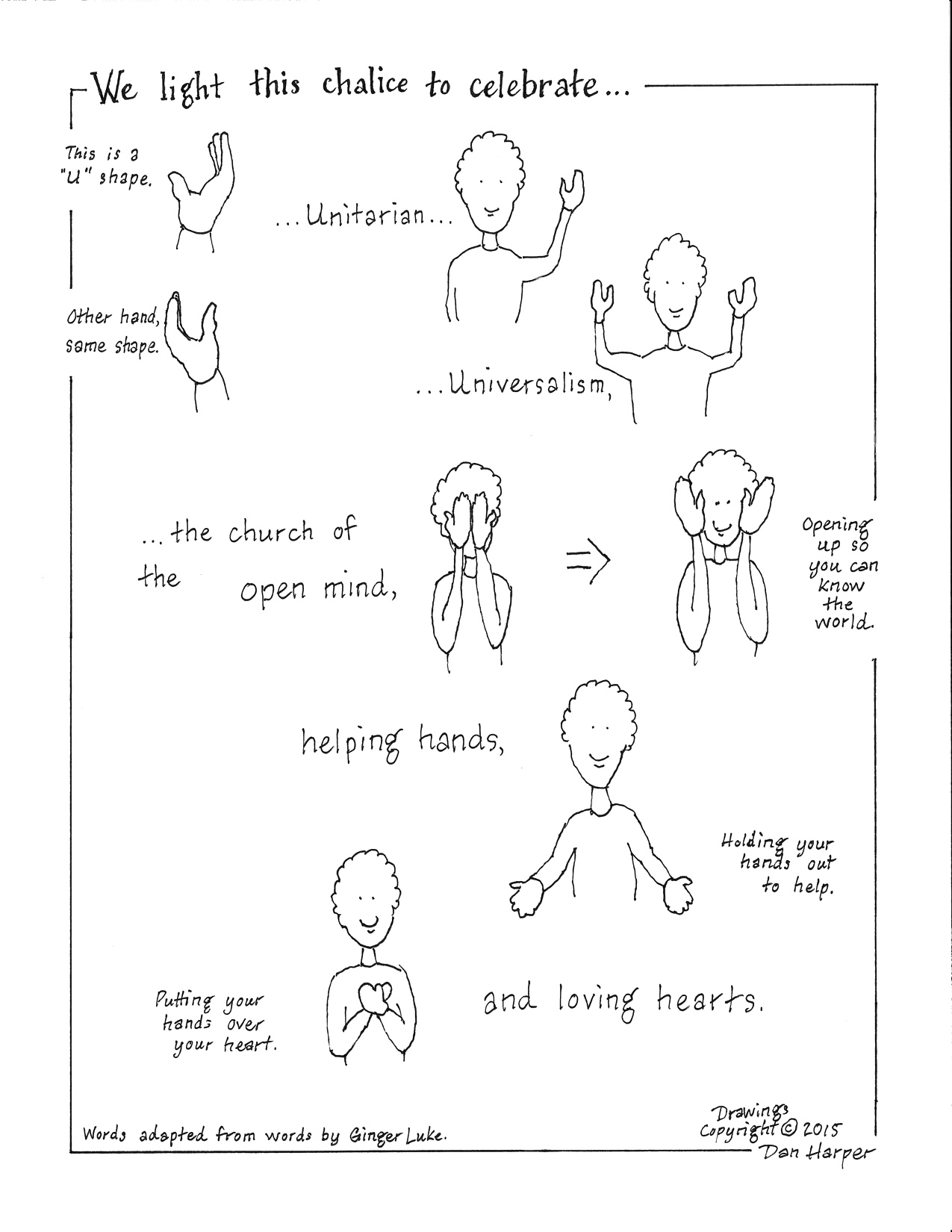

Light a candle or flaming chalice while you say some opening words. Here are some sample opening words (adapted from words by Rev. Ginger Luke) with hand motions:

We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian

[hold up one hand with thumb and forefinger in a “U” shape]

Universalism,

[hold up the other hand with thumb and forefinger in a “U” shape]

the church of the open mind,

[put hands to forehead and open them as if opening a double door]

helping hands,

[hold out hands, palms up, in front of you]

and loving hearts.

[put hands over heart]

Printable PDF with cartoons of the hand motions.

3. Time for check-in

One of the teachers gives the rules for check-in. You can say something like this:

“In just a moment, we will go around the circle, and each person will get a turn to speak. When it is your turn, begin by saying your name. Then you may tell us one good thing and one bad thing that has happened to you in the past week. You may also choose to pass, which means you say your name then ‘Pass.’ Only one person speak at a time, please.”

At the beginning of the Sunday school year, one of the teachers may want to share first to break the ice. Know in advance what you will say, so you can set the tone for everyone else. When one person is talking, you should make sure no one else talks (including yourself).

Note that some classes have their own specific variations on the sharing circle. Ask the other teachers on your teaching team if there is a specific ritual that they have used in past years. Some examples:

— Some preschool classes use a picture of a smiley face and a frown-y face. Children point to the smiley face and say a good thing that has happened to them, and/or to the frown-y face and say a sad or bad thing that has happened to them.

— Some middle school classes have used three jars of water, one with a smiley face, one with a frowning face, and one that says “I wonder.” The middle schoolers each get three marbles, and they drop a marble into each jar while they tell about a good thing, a bad thing, and then finally something they wonder about.

4. Optional elements of the opening circle

After the check-in, you can include other things, like a reading or a song.

2-C. Using your printed curriculum

When you sign up to teach, you get curriculum books. These curriculum books contain fully-scripted lesson plans to make it easier for you to teach. Here’s how to use your curriculum book effectively:

Check the curriculum plan, or check with your teaching team, so you know which lessons are supposed to be taught on which weeks (you can also ask the Minister of Religious Education). Stick to the curriculum plan! I’ll never forget the nine year old girl who came up to me one September Sunday and asked if her class was going to make dioramas of a Judean village. I told her no, not as far as I knew. “Oh good,” she said. “Because we made dioramas of a Judean village two years ago, and we made them last year, and I don’t want to make them again.” The point is obvious — stick to the curriculum plan to keep from repeating the same activities over and over again!

Using the lesson plans in your curriculum books:

When you are new at teaching, you may be tempted to try to use the lesson lans in your curriculum exactly as they are written. Sometimes that’s possible. But many curriculum books have lesson plans designed for 60 to 90 minute time slots, while most Sunday school sessions really only have 30 to 45 minutes to give to the lesson plan. For example, here at UUCPA, kids go to the first 15 minutes of the worship service, then we have our standard opening circle, and our standard closing circle (more on that below) — so really you only have 30 minutes to devote to the actual lesson plan.

That means you have to decide which activities you will drop! First of all, since you’re using a standard opening circle and closing circle, you should drop any opening or closing activities in the lesson plan.

Next, determine which is the single most important activity in the lesson plan. Let’s say the topic of the lesson plan is Noah and the ark. If you have to choose between reading the story of Noah and the ark to the children, and eating animal crackers for snack, I’d say you should probably drop the animal crackers as less important. The way to choose the single most important activity for that lesson is to think about which activity will best help the children grasp the central idea of the lesson.

Now determine which is the second most important activity in the lesson plan. The second most important activity should reinforce the ideas you present in the first activity. BUT if you run short of time, it’s an activity that you could drop without losing too much. To go back to the example of Noah and the ark, if the first activity is reading the story to the children, then the second activity could be drawing pictures of the story.

How many activities do you need for a class? Most lesson plans give the estimated time it will take for each activity. So keep choosing activities until all the activities add up to the amount of time you have for the lesson plan.

The basic class schedule:

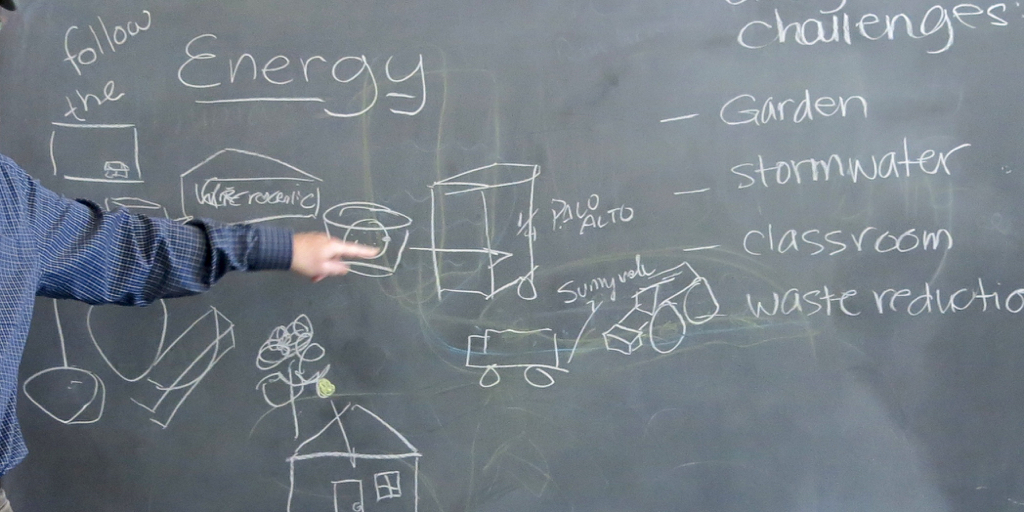

Whenever I teach, I like to make schedule for the class, showing the estimated start times for each part of the class. Here’s a sample class schedule I wrote up for one week when I was one of the teachers of our Ecojustice class at UUCPA:

9:30 — kids go to service in the Main Hall

9:45 — Opening circle (Francesca leads chalice, check-in, reading, while Carol and Dan take attendance)

10:00 — split into two groups: one group goes with Carol and Francesca to work on the garden, one group goes with Dan to attach bee houses to the back fence

10:00-10:05 — look at old bee houses, determine which are still good

10:05-10:10 — walk to back fence, talk about the importance of native pollinators

10:10-10:25 — work on attaching bee houses; determine how many new bee houses we need to make

10:25-10:30 — pick up tools and clean up

10:30 — Everyone joins together in the classroom for the closing circle

And here’s a basic class schedule I wrote up when I was teaching a mixed-age group of children, grades K-5, during Summer Sunday School:

9:30 — kids go to service in the Main Hall

9:45 — Opening circle

Hong takes attendance

9:45, Dan leads chalice and check-in

9:55, Beth leads song

10:00 — Reading the Taoist story “The Useless Tree”

10:05 — Acting out the story

10:15 — Conversation about the story

10:20 — Drawing a huge mural of the Useless Tree

10:30 — Closing circle

My actual lesson plans were more detailed than this — all I’m showing you here are my basic class schedules, timed to the nearest five minutes.

When I make these class schedules, I think about the rule of thumb that says you get one minute of attention span per year of a child’s age. So in the Ecojustice class for middle schoolers, I feel comfortable scheduling an activity that lasts for ten to fifteen minutes. In the Summer Sunday, where the youngest child was 5, I tried to keep the activities to five minutes or less (I made an exception for acting out the story, because the children would be doing such varied things that I thought they could stick with it for a longer time).

And I don’t worry too much if the actual class diverges from my careful lesson plan — as long as I know the class touched on the topic for the day. And as long as I keep in mind the big educational goals: have fun and build community, increase religious literacy, build skills, prepare children to become UU adults.

As you gain experience as a teacher, you may want to modify the lesson plans even more. Here’s a helpful form for planning a Sunday school session: Session Plan (PDF)

2-D. The closing circle

Why a closing circle?

Emotionally, it’s a good idea to have the group come together one last time before leaving Sunday school. Children, teens, and adults all like to have a formal closing.

In terms of educational strategy, a closing circle is your chance to ask the children to tell you what they learned. This gives you immediate feedback on how well they absorbed the lesson.

In terms of religious community, a closing circle allows you and the children to say together the same unison benediction that is used each week in the adult service, which helps tie all ages together in one religious community.

Here’s how to lead a closing circle:

Stand in a circle. The lead teachers then asks everyone to share something they learned or did. Three examples:

— You can ask each participant to show something that he or she has made in class that morning, e.g., hold up a picture they drew and tell the group what they drew.

— You can do a simple review session, asking easy questions of the whole group, and repeating back to them the correct answers, e.g.: “What did we learn today, anyone remember? Who was the person we learned about? John Murray, right! And what did he do? Got stuck on a sandbar, right!”

— You can ask each participant to say one thing they are taking away from the session, one thing they’ve learned or done.

Then have some closing words. Here are some sample closing words:

Go out into the world in peace

Have courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return to no person evil for evil

Strengthen the faint-hearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Honor all beings

2-E. Back-up or sponge activities

Sometimes even the most experienced teachers find that the session they had planned just doesn’t work out. No one knows why this happens — maybe it’s something in the water supply, or Mercury is in retrograde, or all the children had two servings of sugary cereal for breakfast — whatever the cause, even the best teachers find have session plans that don’t work out. But the best teachers always have a back-up activity ready to go in case the main session fails. Here are some suggestions for back-up activities:

— Active games are always a good bet. (Think of playing active games as a way to build community.) “Duck, Duck, Goose” is great for just about any age, and can go on for an hour or more. You can find lots of games on the Games section of this Web site.

— Board games or card games can work well, especially if they are related to the topic of the day. For examples of games related to typical topics, at UUCPA we have Parama Pada Sopnama to use in classes learning about Hinduism; Exodus: The Card Game to use in classes learning about the Hebrew Bible; several board games related to ecology and the environment; etc.

— If you or a co-teacher is musical, singing usually works, especially if you sing songs the children already know.

— Reading aloud works for many groups, so you might want to have a good story book on hand.

— Over time, you usually discover that there is some activity that always works with a certain group of children. I remember a third grade class that loved to draw, and you could always get them to settle down by bringing out paper and crayons. Another group of fifth and sixth graders really liked to do guided meditations, so I always had a guided meditation ready to go. Another class loved to build with Lego brand blocks. If you can find what it is that they love to do, back-up activities are easy to plan.

2-F. Classroom management

Classroom management is the art of maintaining good behavior while enabling every participant to learn and have fun. Here are some tips for improving your classroom management skills:

1. Careful preparation

Careful preparation is the foundation for classroom management. At a minimum, read over the curriculum materials and write out a basic class schedule (as described above) — plus make sure you have back-up or “sponge” activities ready to go in case your main lesson plan does not go well — plus make sure you have on hand any materials or story books needed to teach the class.

If you have time to go beyond the minimum, try the following:

— if there’s an art or craft project in the lesson plan, make it yourself before class

— if there’s a story, practice reading it out loud a few times before class

— if the topic is unfamiliar to you, do some additional reading or study on the topic

2. Imagine how the lesson will go.

As you read over the lesson plan, imagine how the children in your group will react to the activities. As I’m planning for a class, I run a little movie in my head where I imagine I’m teaching the lesson plan to the children I know will be in that group.

Is there a child in the group who has a hard time sitting still for stories? — as you run the movie in your head, think about what it would be like if the children lay on the floor to listen to the story, or if they drew pictures while listening, or had something quiet to hold and fiddle with while you read. Is there a child in your group who needs to move? — think about how you can add some gross motor activities into the lesson plan. Is there a child who is shy and likes quiet? — think about how you might incorporate times for silent refection in the lesson plan. In other words, you go beyond the written lesson plan and think about little things you can do to make everything go more smoothly.

3. Anticipate problems

Anticipate problems before they happen.

Experienced teachers are constantly scanning the group to see how different children are reacting to the lesson. As soon as you see a child’s attention wandering, help draw them back into the lesson.

I remember one class where I was telling one of the Jataka tales, an Indian folk tale that tells a story of one of Buddha’s previous lives. I saw one girl’s attention wander, and she was all ready to have a side conversation with her best friend sitting next to her. So I stopped the story and said, “While I read the story, we’re all going to act it out, and YOU [pointing to the girl whose attention had begun to wander] are going to be Buddha.” She grinned, sat in the lotus position next to me, and was no longer a potentially disruptive influence — and her best friend, no longer sitting beside her, was happy to listen quietly.

Typical problems that you can anticipate include:

— Best friends chatting with each other

— Siblings hitting or fighting with one another

— Kids who have a hard time sitting still needing to fidget

— Etc.

4. Positive contact with every child

Make positive contact with every child at least 3 times per class.

If children know you are paying attention to them, they are more likely to stay contentedly engaged. But it’s easy for teachers to focus on the children that they find easiest, or most attractive, or most fun. To keep myself honest, and to give every child adequate attention, I keep track of the number of positive contacts with each child.

Here are some things that count as a positive contacts: smiling at the child; catching their eye so they know you see and recognize them; praising something the child does; showing the child how to do something; laughing when the child says something they intend to be funny; commiserating with them if something goes wrong…. You get the idea.

To get a little mystical, a positive contact is a moment when you recognize the deep humanity of a child, and react to them with love and kindness. Now I admit I have found it hard to love certain children, and in those cases I fall back to the bare minimum of recognizing their inherent worth and dignity. But if we can express love and kindness to each child, at some level, classroom management becomes easier — plus it’s a good spiritual discipline for us adults!

5. covenants

Make a covenant — a set of promises everyone in the class makes to each other — and stick to it.

Often, I find it helpful to set up a “covenant,” or set of behavioral promises, early in the Sunday school year — see Chapter 4-C below.

Once you make the covenant, post it somewhere in your room, and have everyone look at it any time someone breaks those behavioral promises. I have found that when the children have some say in making the covenant, they have some investment in making sure everyone sticks to it.

6. What to do when things go wrong

Sometimes, even the best teachers find that behavior gets out of hand. First of all, if something’s about to happen where someone might get hurt, it’s OK to raise your voice — but never touch or physically restrain a child unless bodily harm is imminent.

In cases where bodily harm is NOT imminent, then your best bet is to somehow stop all action and have everyone sit down.

I remember one Sunday school teacher in a middle school class who was also an athletic coach, and she hung a whistle around her neck and blew it if she felt she had to “stop the action” — she hardly used it at all, and she made it into something humorous so they kids could laugh, but the few times she did blow the whistle everything stopped. (Now I’m NOT an athletic coach, and I would never use a whistle, but I have a big voice, and I AM willing to use that if necessary.)

At the other extreme, I remember a very spiritually grounded man who could stop his class simply by being silent — slowly, all the children would realize that he was sitting there completely silent and looking sad, and slowly the silence would spread until everyone was quiet. How he did it I’m not sure, but it seemed to be sheer spiritual power. (Now I’m not that spiritually advanced, but I have managed to bring a rowdy group to a complete standstill by talking softly so that everyone had to quiet down so they could hear me — and they did quiet down, because they were curious why I was talking so softly!)

Once you stop all the action, have everyone sit down. Tell them what you saw going wrong. Remind them of the covenant. Tell them that in order to have fun, things cannot get out of control. hen ask them to help problem-solve — how can we, as a group, keep this from happening again?

Once they’ve problem-solved, you should be ready to go back to the lesson plan.

Chapter 3: Models of teaching and learning

Models of how people learn, and how we can best teach different learners, are useful tools for teachers. In their teaching toolkit, every teacher should have at least a few models of teaching and learning.

3-A. Developmental stage theories

What are developmental stages? Anyone who has spent time with children knows that they change as they grow older. Developmental stage theory says that certain developmental changes take place at somewhat the same age. there are several different types of development where we can identify developmental stages:

1. Cognitive development.

Jean Piaget did the groundbreaking work in cognitive development. He showed conclusively that in some ways, children actually think differently about the world than do adults. To give one example, infants do not have the cognitive ability to know that a thing exists even when they can’t see it. For example, if you show an infant a ball, then put that ball behind your back where they can’t see it, for them the ball no longer exists — until you bring it out from behind your back and they see it again. But by the time they are about two years old, children develop what Piaget called “object permanence” — they know that objects exists even if they cannot sense them at the moment.

For Sunday school teachers, there are three stages of cognitive development that you should know about.

Children at about ages 4 through 7 are in the pre-operational stage of development; more specifically, they are in the intuitive sub-stage. In this stage, they are not yet able to carry out certain logical thought processes. Some examples: they have problems understanding that some actions are reversible (e.g., if you fill a round pitcher with water from a square pitcher, you can turn around and pour the water back into the round pitcher); they are not be able to use transitive logic (e.g., if X is less than Y, and Y is less than Z, they don’t see that X must be less than Z); etc. Yet at the same time, this age group is very curious and they ask a lot of questions. They have begun to use primitive reasoning, but some kinds of knowledge are still beyond them.

Children at about ages 8 through 11 are in the concrete operational stage of cognitive development. At this age, children are capable of using inductive logic, though they still have difficulties with deductive logic. They have also gone beyond the egocentrism of the earlier stages, and are increasingly able to understand the points of view of persons other than themselves. Children at this stage of development are not at the stage where they can do abstract thinking, because they are still limited to actual objects, to actual events.

Young people at about ages 11 through 15 are consolidating the use of formal operational thinking. At this age, they gain the ability to use abstract concepts, and to think abstractly without being limited to concrete objects or concrete events. They begin to engage in hypothetical reasoning, “what if” scenarios that are beyond the capacity of earlier cognitive stages. Persons at this age learn to think about thinking, so that they can watch how they think and monitor their own thought processes.

Though it can be tough going, teachers may find it worth their while to learn more about Jean Piaget’s model of developmental stages. here are two articles worth reading: Jean Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development offers a useful overview, plus criticisms of the theory; Wikipedia’s article on Piaget’s theory of cognitive development goes into more detail about developmental stages. I highly recommend the print book Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive and Affective Development: Foundations of Constructivism by Barry J. Wadsworth (Allyn & Bacon), 5th ed.

2. Psycho-social development.

There are a number of models for psychosocial development — that is, how humans develop in their social interactions. I have found the psychosocial developmental models of Erik Erikson and Robert Kegan to be useful in Sunday school settings, and I’ll quickly summarize them. However, you should be aware that no model of psychosocial development is as well-developed as Piaget’s model of cognitive development (and even Piaget’s model is subject to much debate), so don’t take these models as absolute.

Erik Erickson was a psychoanalyst who postulated that humans go through eight stages of psychosocial development. Each stage can be characterized by a basic virtue, as well as by a “psychosocial crisis.” Here are the eight stages, each with its basic virtue:

1. Trust vs. mistrust, ages 0 to 1-1/2 years — Hope

2. Autonomy vs. shame or doubt, ages 1-1/2 to 3 — Will

3. Initiative vs. guilt, ages 3 to 5 — Purpose

4. Industry vs. inferiority, ages 5-12 — Competency

5. Identity vs. role confusion, ages 12-18 — Fidelity

6. Intimacy vs. isolation, ages 18-40 — Love

7. Generativity vs. stagnation, ages 40-65 — Care

8. Ego integrity vs. despair, ages 65+ — Wisdom

Erikson is probably best know for the term “identity crisis” to name a crisis that characterized adolescence, and his 1968 book Identity, Youth, and Crisis is still worth reading.

As a Sunday school teacher, I have found Erikson’s model to be fairly useful. I don’t teach preschoolers much; but when teaching elementary ages I do find it useful to think about how to help the children find a sense of competency; and when working with adolescents, I find it very useful to think about how to help them find a sense of identity while not getting lost in role confusion.

If you’d like to learn more about Erikson, try this online article, Erik Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development (Wikipedia’s article is not very good, so skip it.) And Erik Erikson’s 1959 book Identity and the Life Cycle is short and very readable — highly recommended.

Robert Kegan is another psychologist whose model of psychosocial development is worth investigating. Some of his ideas appear in the table below.

3. Faith development.

There is a model of “faith development.” James Fowler is the originator, and best-known proponent, of faith development. However, Fowler’s definition of “faith” seems sketchy at best, and I don’t find his research particularly compelling. I am particularly troubled by the fact that he identified his highest developmental stage through the evidence of only one person in his study — I don’t see how you can describe an entire developmental stage using a sample size of one.

Nevertheless, there are some respected religious educators who find faith development to be a useful model. To learn more, read Fowler’s 1981 book Stages of Faith.

4. Lev Vygotsky’s model of human development.

I use Lev Vygotsky’s model of human development all the time. But I have yet to write up a good summary of it. So I’ll point you to some great Web resources.

a. A useful and concise explanation of Vygotsky’s key concept, the Zone of Proximal Development, may be found here.

b. A brief but useful overview of Vygotsky’s ideas on learning in community may be found here.

c. A quick introduction to Vygotsky for those working with preschoolers, emphasizing the importance of development through play, may be found here.

d. For an introduction to the very important Vygotskian concept of “scaffold and fade,” read this article.

Over and over again, I have found that developmental models and teaching strategies growing out of Lev Vygotsky’s work have absolutely been the most useful in Sunday school settings. As you continue to develop as a teacher, I particularly suggest you learn about community learning, “scaffold-and-fade,” and the Zone of Proximal Development — I think you’ll find these strategies extremely useful!

6. Critics of developmental stage theory.

Religious education scholars like Gabriel Moran and Robert Pazmino have been critical of any developmental theory as applied to religious education. Pazmino and Moran argue that anyone, of any age, can have direct experiences of God (or, as we might say, of the transcendent mystery of the universe). Moran has also argued that the very concept of development leads to the uncomfortable sense that children aren’t fully “developed,” and therefore may not be fully human.

In another criticism, a number of scholars have argued that any developmental theory should be able to accurately predict developmental changes. Yet since all developmental theories are really designed for large, statistically valid, groups of individuals, it is not clear whether developmental theories can be usefully applied to individuals.

7. Faith formation.

Faith formation isn’t a developmental model so much as it’s an ANTI-developmental model. As such, it has become widely used as a model for understanding how children learn how to do religion.

Originally, faith formation grew out of Christian religious education. The image of “formation” comes from images in the Bible of God forming humans as a potter forms clay, e.g., Isaiah 64:8, “We are the clay, you [God] are the potter.” (Unitarian Universalists will be interested to know that image of a god who was a potter occurred elsewhere in the Ancient Near East; for example, the Egyptian god Khnum created human beings out of clay on his potter’s wheel.) Human development can thus be understood, not just as a natural process arising from physiological and social growth, but also as a process that is guided and shaped (literally!) by God.

The concept of faith formation has been adopted by many Unitarian Universalists who are not necessarily theists. So Unitarian Universalists might want to consider the image of faith formation differently from the Christians. Unitarian Universalist faith formation might say something like: human beings do not learn faith in a classroom, but rather we are formed by our lived experiences with faith. Thus, while for the past century of so education has been seen as a way for us to intentionally systematize and guide human development, faith formation argues that when it comes to religion, human development is best guided — not by formal education — but by intentional participation in traditional religious activities like worship services, and religious activities done at home.

I’ll be honest. I have not found faith formation to be a particularly useful model. It just doesn’t seem to be an accurate model of what I observe in children, nor with what I observe happening in families or in congregations.

Nevertheless, most models of learning have at least something useful for us teachers. Advocates of faith formation have created a large number of resources that can help us with religious education. A quick Web search will bring up lots of hits on “faith formation.” (I won’t try to point any specific Web sites out, since I realize I’m competent to judge which faith formation Web sites are best.)

8. Summary

In spite of the criticisms, developmental theory remains a useful tool for Sunday school teachers. It can be useful to have a general idea of what to expect from different age groups. Developmental theory can help us to understand which types of activities work best with which age groups.

Most importantly, developmental theories provide us teachers with useful models that may help us navigate through difficult real-world situations. I use Erik Erikson’s model all the time when working with adolescents, to help me figure out what’s going on when they are behaving badly — often, I am able to frame the situation as a form of the conflict between identity and role confusion, I can hep the adolescents move away from role confusion, and whether or not Erikson’s model is supported by the latest brain science it sure helps me deal with behavior problems. Similarly, I use Vygotsky all the time when working with elementary age children. Is there really such a thing as the Zone of Proximal Development? It doesn’t matte to me, because I find the scaffold-and-fade strategy works well, and I also find that community learning is a hugely successful strategy in Unitarian Universalist Sunday schools.

In short, if a developmental model — or any other model of how people learn — allows you to become a better teacher, then use it!

SUMMARY CHART FOR APPLYING DEVELOPMENTAL MODELS

| Social skills | Cognitive abilities | Skills and abilities important in UU congregations | Religious experiences | Good choices for Sunday school activities | |

| Babies | Focused on self and parents | Begin to talk | Love and joy | Security, love | Loving care |

| Young children (age 3-5) | • Parallel play develops towards real friendships • Family very important | •No strong division between reality and fantasy | • Sing simple songs •Listen to stories • Sit in some worship services • Ask to go to church | • Lots of questions about “God” and other big religious issues • Probably have transcendent experiences | • Play • Hear stories • Learn how to be in a group • Ask questions and be listened to seriously |

| Primary (ages 5-7) | • Peer friendships • Imaginary friends • Boys and girls strongly separate • Church and school as institutions begin to be important | • Beginning of reading and writing | • Know songs and hymns • Sit in worship services • Guided meditations • Memorize things (e.g., congregation’s covenant) | • Transcendent experiences, including direct experiences of “God” or similar • Early under-standing of what it means to be part of a religious community | • Play • Hear stories • Guided meditation • Simple yoga • Ask questions and listen to answers |

| Elementary (ages 7-11) | • Best friends important •Self-sufficiency and competence •Institutions and persons held to standards of fairness and justice | • Can read and write easy texts • Can listen to lectures | • Participate in meetings • Understand worship services and sermons • Know facts about religion • Ask good questions about fairness and justice • Initiate social action projects | • Experience religion as institutional • Experience common worship and other communal experiences as communal | • Play group-building games • Hear stories • Discussions about their questions • Social action projects • Learn facts • Perform plays |

| Intermediate (ages 11-14) | • Family and institutions begin to become secondary to shared internal experiences with peers and trusted adults • Girls and boys begin to mix again • Sexuality re-emerges as a powerful force | • “Concrete operational” thinking — understand complex concepts | • Question things that are “givens” • Understand and act on feminism • Come to terms with homophobia • Do social justice • Open to new ideas and concepts • Speak in public • Basic leadership | • Experience the religious dimensions of friendship • Experience the religious dimensions of sexuality • May have profound religious experiences that they want to make sense out of | • Conversation • Check-in • Questions and question boxes • Social education, social service, and even direct action • Group-building games and initiatives • Worship services • Spiritual practices |

| High school (ages 14-19) | • Progressive social separation from family of origin • Progressive integration into peer group and (ideally) wider community | • Full abstract thinking develops: “formal operational thinking” | • Serve on committees • Participate fully in worship • Hold their congregations to high standards (Essentially same as adults) | Same as above, same as adults | •Building community • Worship and spiritual practicies • Leadership development • Classes and discussions |

Outline of multiple intelligences theory

Beginning in the 1980s, Howard Gardner, a psychologist at the Harvard School of Education, began to grow interested in how people learn. He began to research brain physiology, and he looked at experts in a variety of fields. Over the next two decades, Gardner developed a complex and nuanced theory of learning.

First, Gardner theorized that human beings have at least eight “intelligences.” rather than the one so-called intelligence that is tested by the usual paper-and-pencil intelligence tests. According to Gardner, each of us can have a different mix of strengths among these eight intelligences. He began to talk about “multiple intelligences,” and it is through this term that his theory is best known. His theory has been embraced by practicing educators who find it a useful model to help understand how different people learn in different ways. However, Gardner himself is quite emphatic that multiple intelligence theory is not the same as learning styles — in fact, Gardener has written that the notion that people have learning styles is “incoherent.”

The eight intelligences that Gardner identified are listed in the table on the next page, along with a brief description of each intelligence, an example of an expert who rates high in that intelligence, and some activities that educators can use to reach persons strong in that intelligence.

Applying multiple intelligences theory to religious education

Howard Gardner’s theory is useful for those of us who are Sunday school teachers. Most Sunday school teachers will be personally strong in two or three of the multiple intelligences. For example, Mark, a Sunday school teacher I worked with some years ago, worked as an architect, and he had particularly strong spatial, linguistic, and interpersonal intelligences. Yet Mark was less strong in musical and bodily/kinesthetic intelligences. Not surprisingly, Mark did lots of art projects in Sunday school, and he also liked discussions and group activities. Multiple intelligence theory helped Mark understand that he tended to neglect musical and bodily/kinesthetic intelligences — yet there were children in his group with very strong bodily/kinesthetic and quite strong musical intelligences. He was then able to plan activities that would play to the strengths of those children. For the bodily/kinesthetic children, he planned building projects that involved manipulation, and he also planned active games that promoted cooperation — thus combining his strengths with the strengths of those children. He felt he was absolutely hopeless at music, so he made a point of inviting another adult to visit his group and sing some songs.

The net result for Mark was very positive. He came to realize that some of the behavior problems he was having were with the children who had strong bodily/kinesthetic and musical intelligences. When he helped them use their strengths in church school, they became much more involved and created fewer behavior problems. Second, he felt he was doing the right thing. We Unitarian Universalists say we believe in the inherent worth and dignity of every person, and using multiple intelligence theory can be a way of valuing the peculiar strengths of each child in your church school group.

New advances in brain science

Multiple intelligences theory grew out of the then-novel concept that brain science can (and should) inform our educational practice. But brain science has made significant advances since Howard Gardener first published his ideas Where does this leave multiple intelligences theory?

First of all, I feel that learning more about brain science and its application to education is worth our while. Back in 2011, at Religious Education Week at Ferry Beach Conference Center in Saco, Maine, I gave an informal talk on how new advances in brain science might affect how we do religious education, and you can read the text of that talk here. One of the key points I make in this talk is that learning more about brain science as it applies to education can help us teachers to better understand how children learn — and ultimately to be more sympathetic and helpful as teachers.

Second, multiple intelligences theory continues to evolve. Multiple Intelligences Oasis is a Web site associated with Gardner and others working on multiple intelligences theory, with lots of resources aimed at teaachers — you can find it here. This is a great place to start learning more about multiple intelligences theory.

Third, it’s always important to remember that ANY model we use in education is just that — a model. When you are teaching real, live children or teens, educational models will help you become a more effective teacher. But no one model will ever cover all the situations you encounter as you teach. The most effective teachers learn how to use more than one model, and they keep checking their model against the realities of teaching.

| Name of intelligence | Brief description of this intelligence | Experts who rate high in this intelligence | Activities to use in UU Sunday schools |

| Linguistic | “sensitivity to spoken and written languages, ability to learn languages, capacity to use language” | Lawyers, speakers, writers, poets | Tell stories, lead discussions, ask questions, give children opportunities to speak (in worship, in front of class) |

| Logical / Mathematical | “capacity to analyze problems logically, carry out mathematical operations, investigate issues scientifically” | Mathematicians, logicians, scientists | Use worksheets and puzzles, offer logical presentations of materials, count things, argue |

| Musical | “skill in the performance, composition, and appreciation of musical patterns” | Musicians | Sing songs, listen to music, compose songs and raps, play rhythm games |

| Bodily / kinesthetic | “the potential of using one’s whole body or parts of the body (like the hands or the mouth) to solve problems or fashion products” | Dancers, athletes, actors, craftspeople — To some extent also: surgeons, mechanics, bench-top scientists | Play active games, use dance and creative motion, act out skits, manipulate or make objects |

| Spatial | “the potential to recognize and manipulate the patterns of space” | Navigators, pilots, sculptors, chess players, graphic artists, architects | Do art projects (e.g., make drawings), explore church buildings, make forts or hiding places, draw maps |

| Interpersonal | “a person’s capacity to understand the intentions, motivations, and desires of other people, and consequently to work effectively with others” | Salespeople, teachers, clinicians, religious leaders, political leaders, actors | Group problem-solving and initiatives, group games, diversity or anti-racism activities, worship services |

| Intrapersonal | “the capacity to understand one’s self, to have an effective working model of oneself” | (Religious leaders?) | Meditation, worship services, silence, personal growth activities |

| Naturalist | capacity in “the recognition and classification of the numerous species — flora and fauna — of his or her environment” | Naturalists, biologists, hunters, anglers, farmers, gardeners, cooks | Plant seeds or bulbs, cook starting with basic ingredients (i.e., not from packaged mixes), watch animals, go outdoors |

3-C. The traditional three-way learning styles model

Many of us teachers still use the traditional three-way model of learning styles. This model isn’t supported by clincial evidence, yet many teachers still find it works for us in the classroom.

This model says that there are three basic styles of learners — visual learners, auditory learners, and kinesthetic learners. These correspond very roughly to spatial, linguistic, and kinesthetic intelligences in the multiple intelligences model — just remember that each of these three learning styles covers more territory, and is less well-defined, than the corresponding multiple intelligence.

The traditional three-way learning styles model is obviously overly simplified. But the simplicity is exactly what makes it so useful to teachers. Instead of trying to think about eight different intelligences, or instead of trying to remember all the latest research on brain science, you only have to think of three learning styles.

So when you’re planning a lesson on a specific topic, you might come up with three activities to reinforce the learning about that topic. For example, if you’re doing a lesson on the great Universalist minister John Murray, you might first tell a story about how he came to North America (verbal learning), then you might have the children act out that story (kinesthetic learning), and finally you might have the children draw pictures of the story (visual learning). That way, you’ll reach a wider range of learning styles than if you just read the story and talked about it.

Similarly, when you’re in the middle of teaching and you face some emerging behavior problems, you might ask yourself — have I been relying on talking and lecturing too much? and by so doing, have I lost some of the learners? I think this is, in fact, a common problem. Teaching verbally, using words, always seems more efficient. But if you rely too much on verbal learning, many children will start feeling bored. As soon as you have bored children, you will see behavior problems developing (the same is true of adults, by the way — when we get bored, we tend to act out, too!).

The traditional learning styles model can be useful, even though there’s no evidence that children have specific learning styles. The reason the model is useful, I believe, is that it is really a model about teaching styles. Thus I use this model to spark my creativity as a teacher, because it makes me think about different ways I can teach a topic. If it sparks your creativity as a teacher, then this is a useful model. Just don’t pretend that it’s supported by brain science, or clinical evidence!

For more about how the “learning styles” model is not supported by evidence, read this essay.

3-D. How to use games, songs, movement, and more

Both multiple intelligence theory and the traditional three-way learning styles model suggest that teaching must be more than lectures and discussions. Lectures and discussions are great for people with a strong linguistic intelligence, but lectures and discussions may not reach children with, say, strong bodily/kinesthetic or naturalist intelligences.

Since different people have different strengths when it comes to learning, the best church school teachers will plan a variety of activities over time. With that in mind, below is my list of the top five most-neglected teaching methods in Sunday schools today. Try some of these, and see what a difference it can make with children.

— a. Acting, skits, and plays — When you act out a story or skit, you can reach just about every one of the multiple intelligences. Since we can’t always assume children can read, the church school teacher can narrate the skit or play, or children can memorize simple lines.

— b. Play cooperative games — See the Games section on this Web site. For books of games, I like The New Games Book and its sequel, More New Games — it is out of print, but available in many libraries and via online used booksellers like Alibris.com. Also useful are Win-Win Games for All Ages by Josette and Ba Luvmour, and Team Building Activities for Every Group by Alanna Jones. Cooperative games work well at developing interpersonal intelligence, and can also feed bodily/kinesthetic, spatial, logical/mathematical, and other intelligences (depending on the game).

— c. Sing songs — 40 years ago, music used to be a central part of Sunday school, but it has become neglected. Many of the standard curriculums have songs included, or ask me for suggestions. If you can’t sing, find an adult who can help you out. If you want to learn how to lead songs for children, an excellent resource is the book Sing and Shine On by Nick Page and the associated song book Sing With Us — ordering information available here.

— d. Do creative movement — You don’t need to be a dancer to do movement with children. You can do silly hand motions with songs, create weird dances together, take stretch breaks. If your congregation has the old Haunting House curriculum, it included a booklet on doing creative movement with children. Also useful, though dated, is the pamphlet Using Movement Creatively in Religious Education by Pat Sonen (Unitarian Universalist Assoc., 1963), sometimes available used through Alibris.com.

— e. Go outdoors — Unitarian Universalists claim to value the interdependent web of all existence, so go outdoors and experience it with the children. (If you go off church property, remember to follow all policies regarding field trips!)

3-E. Is it school — or something else?

When I say “Sunday school,” do you think about a traditional classroom, with children sitting quietly at desks arranged in rows, while in the front of the classroom a teacher lectures about religion? For some people, that’s what Sunday school is — a classroom with children sitting in rows, listening to lectures about religion. But in the quarter century that I’ve been a religious educator, I’ve never seen a Sunday school classroom that looks that way!

Here are some other ways to think about Sunday school:

a. Sunday school can be like summer camp.

In summer camp, you do fun things that you wouldn’t ordinarily do elsewhere, you sing silly songs, you make friends, and you feel like you’re doing out of the ordinary routine of life. More and more, I try to make Sunday school feel like a little one-hour dose of camp. The silly little rituals we do at the beginning and end of class — the chalice lighting with the hand motions, and repeating the Unison Benediction — this is not unlike the rituals that make summer camp so memorable.

b. Sunday school can be like a small group ministry session.

Small group ministry sessions are great. You get to sit around with sympathetic, like-minded people and talk about the important things that are going on in your life. Kids also like to participate in age-appropriate small group ministries. That’s why I like to start every Sunday school session with a time for check-in — it’s a way to do small group ministry for kids. (And when the check-in goes for 20 minutes instead of the 5 minutes I planned for, I let it go — sometimes kids really need a place where they can talk about what’s going on in their lives.)

c. Sunday school can be like an intergenerational community.

These days, so many of our activities are segregated by age. When kids spend time with adults, usually those adults are either parents, or teachers, or coaches; in other words, people who are clearly authority figures. But Sunday school teachers, while we are clearly authority figures, do not give out grades or drop someone from the team. As Sunday school teachers, we are more like companions on the journey of life, older and more experienced and perhaps wiser, but we can be willing to admit that we too are sometimes still unable to answer life’s big questions. Thus, even while we remain firmly in charge of the Sunday school class, we can be more vulnerable — and in this way we can help create a truly intergenerational community.

Sunday school can be like a worship service.

Imagine a worship service without a sermon (I like that idea, because I am not a strong auditory learner!). Imagine a worship service where you get together with a small group of people, tell each other something about your lives, maybe listen to a story and talk about it together, or work on art projects together. Imagine that you spend 40 or 50 minutes with this small group of people, a time where your day-to-day concerns and anxieties fade into insignificance. Imagine that at the end of the worship service, you all stand around in a circle holding hands and say some closing words together. And sometimes that’s exactly the feeling that I get with a Sunday school class — the class feels like a time when we come together and re-connect with something important.

So there you have three ways to re-imagine Sunday school. I’ll bet you can think of several more (Sunday school is like a hands-on children’s museum, Sunday school is like a party…). I know when I teach Sunday school, I never have kids sitting at rows of desks! So get that image out of your head, and think of Sunday school as a summer camp, an intergenerational community, a worship service….

Above: A teacher coaching a middle schooler on how to safely use a power tool.

Above: Children listening to an adult talk during social hour.

Chapter 4: Procedures and policies

This chapter provides a quick summary of the policies and procedures at the Unitarian Universalist Church of Palo Alto.

If you need a substitute at the last minute, first, contact the other members of your teaching team to see if they can fill in (call, use online chat, or something where you get an immediate response). If you can’t get through to anyone, contact the Minister of Religious Education or Religious Education Assistant directly.

Basic supplies are stored in a rolling cart in each room. If your rolling cart is missing, please let the RE Assistant know immediately!

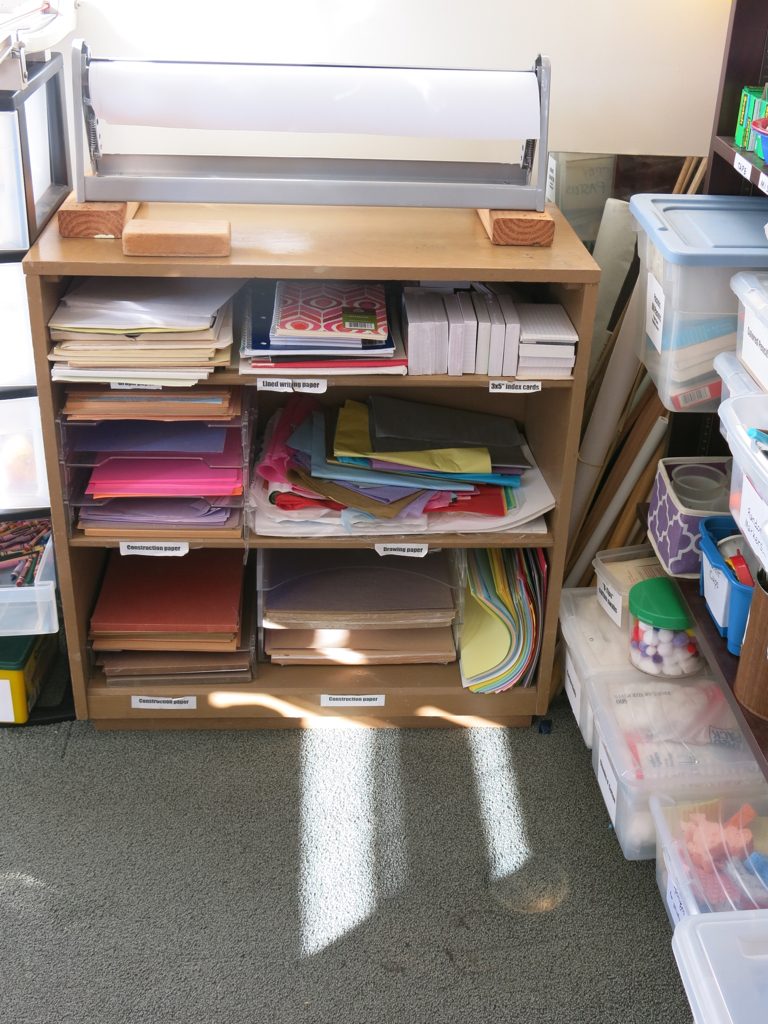

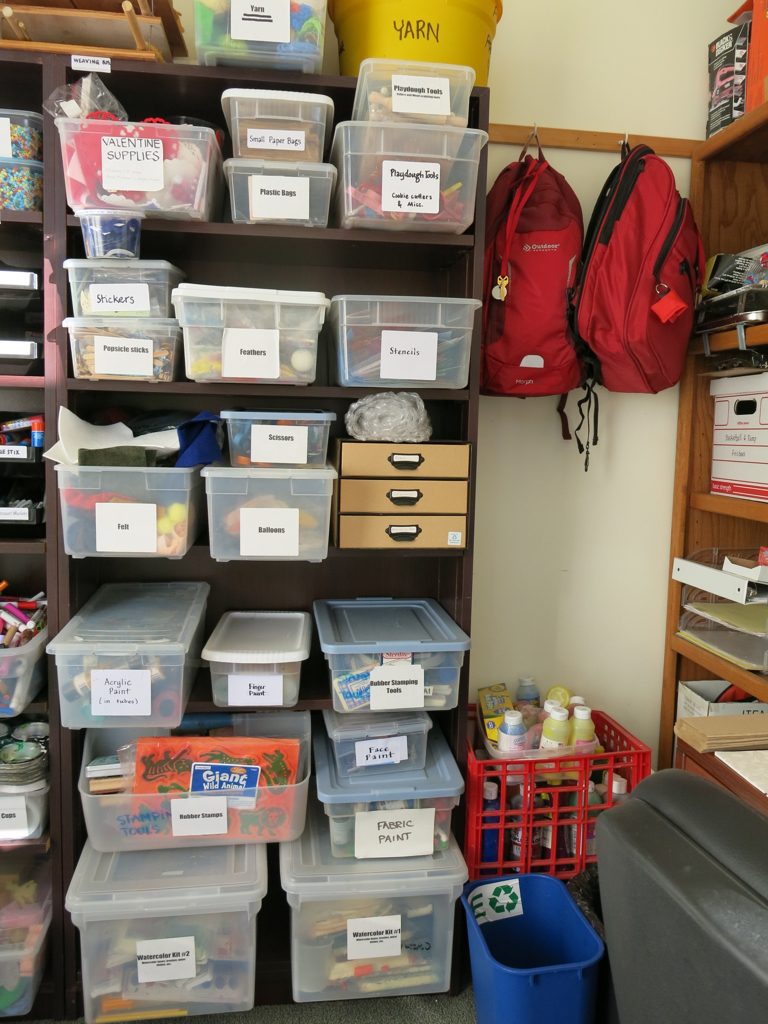

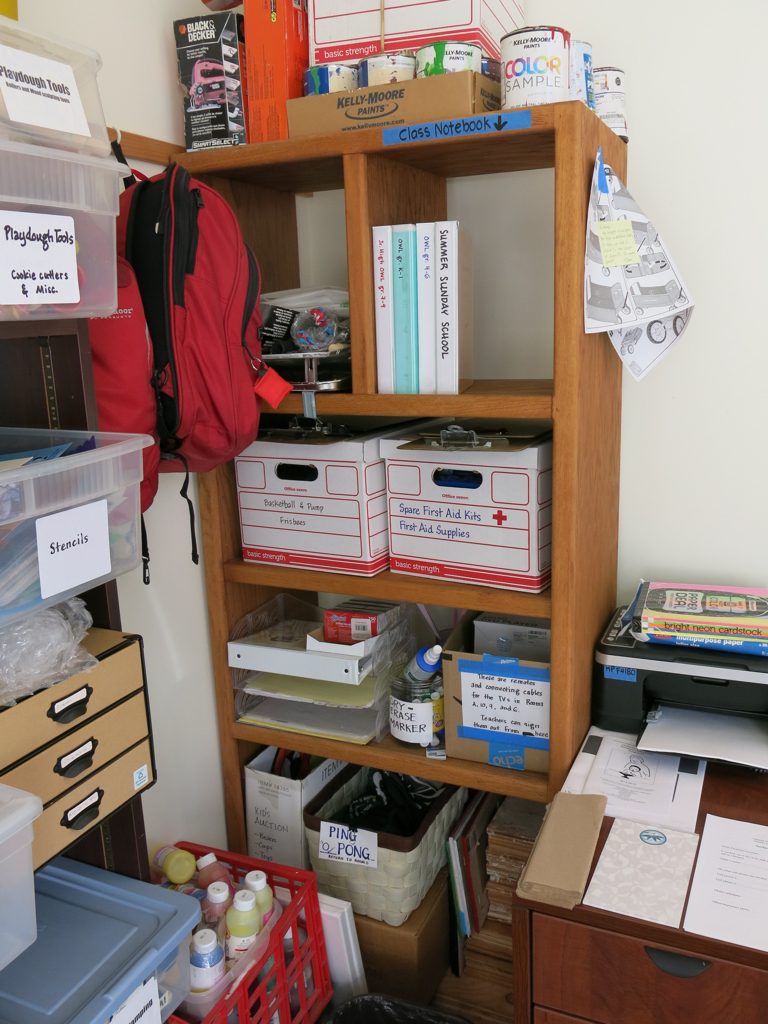

Other consumable supplies are available in various places. The most commonly used supplies are in the RE Assistant’s office, Room C (see below for photos of the supplies in Room C). More specialized supplies are in the closet in Room 5. Games are in the closet in Room 6. Children’s books may be checked out of the library, which is in behind the church office. Children’s books that go with the preschool curriculum, and the Picture Book World Religions curriculum are in the closet in Room 8.

How about buying special supplies for a special project for your class? Our budget for supplies is fairly tight, and I have to approve any purchases in advance. (Also, we may already have what you need.) Once I approve the purchase, you can go out and buy the materials, submit a reimbursement form to me with all receipts attached, and I’ll get you the check. Or if you give me enough advance notice (2-4 weeks), I can order supplies for you.

Audio-visual equipment is is most rooms. Remotes and connecting cables are stored in the RE Assistant’s office. If you need to know how to use the equipment, please ask.

Our philosophy on discipline assumes that everyone has a role in preserving harmony.

Teachers

Teachers create a comfortable, inviting environment. This means that you sprepare in advance for each session, and have back-up plans ready in case your main plan does not work.

Teachers set firm limits. Make clear what your expectations are, and what the consequences are if children do not live up to your expectations. Standard guidelines for behavior are set out below, in “Setting limits.”

Children

Children should help to develop and agree upon a set of expectations, and consequences. Children can be allowed to help one another to engage in “right action,” by reminding one another which actions are acceptable and which are not.

Teachers can help children learn the most important rule: No put-downs. Some UU teenagers used to phrase it this way: “No harshing on anyone’s mellows,” i.e., no put-downs, statements that disparage others, or any actions that hurt someone else’s emotional well-being. These teenagers developed this rule, and were quite firm about enforcing it — if anyone (including adults) transgressed, they would be required to say three nice, affirming things about the person whose mellows they had harshed.

Making a covenant

Children should have a hand in setting rules for the classroom. While you may develop a group consensus over time without a formal procedure, I recommend that you establish a written covenant of behavioral promises early in the year.

There are some non-negotiable rules for everyone in the religious education program. You should make these rules clear to the children in age-appropriate ways:

- No interpersonal violence (or “No hitting”)

- For reasons of safety, children must ask an adult before leaving the room (“Ask an adult if you can leave”)

- Be good stewards of the church property (“No breaking things or wasting materials”)

- Everyone waits their turn to speak

- Everyone cleans up their own messes

- Disparaging comments are not appropriate to a church setting (“No put-downs”)

Setting limits

If the above expectations are not met, you, the teacher, may use one of the following techniques. They are listed in approximate order of severity:

(1) Have the assistant teacher sit with the disruptive child, to help that child stay focused.

(2) Remove the disruptive child from the group by having them work on a quiet independent project, or read a book quietly in a corner of the room, with the help of the assistant teacher.

(3) Ask the Associate Minister of Religious Education to help problem solve.

If you run into behavior problems and discipline problems, remember to tell your co-teachers what happened and what steps you took so that we can keep a consistent approach. At the same time, remember that children, like adults, have bad days and grouchy days, and that as they grow their whole attitude can change very quickly.

4-D. About our child and youth protection policy

Our entire safety policy, as approved by the UUCPA Board of Trustees, is available online here. Similar to most organizations that work with legal minors, UUCPA requires all volunteer teachers to do an annual safety training, to sign the Code of Ethics, and to undergo a criminal background check.

4-E. About our emergency and health procedures

Each year, all teachers review our emergency and health procedures during the mandatory annual safety training.

Photos showing the supplies in Room C, moving from left to right around the room (click on the image to enlarge it):

And to end this Teacher’s Manual, here’s one last photo of kids and adults together in Sunday school:

Above: Learning how to use a 3-D printer in Sunday school.