Greek Myths, v. 1.0

A curriculum for upper elementary grades

Compiled and edited by by Dan Harper and Tessa Swartz

Copyright (c) 2014 Dan Harper and Tessa Swartz

Lesson plan and leader resources copyright (c) 2015 Dan Harper

Back to the Table of Contents | On to Session Two

How Persephone Disappeared, and What Demeter Did

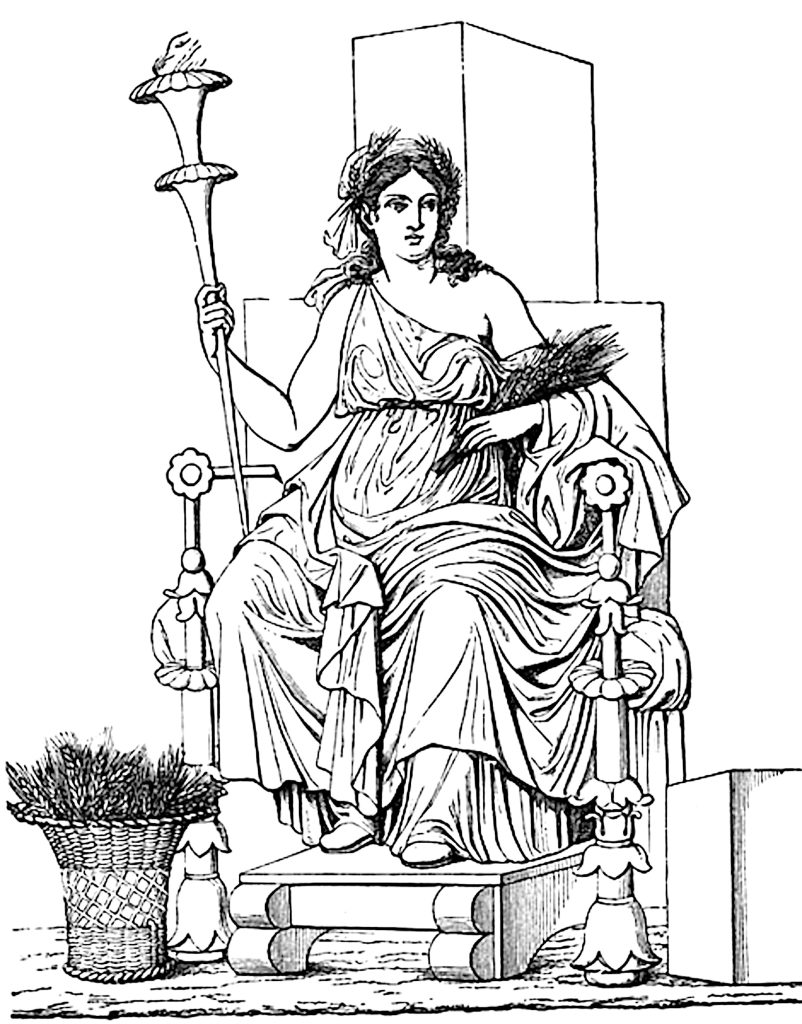

Rich-haired Demeter, goddess who strikes awe in the hearts of all humankind, the goddess of the wheat-fields, goddess of farming and agriculture — Demeter had a daughter named Persephone.

Once upon a time, trim-ankled Persephone was playing with the daughters of Oceanus. They roamed over a soft meadow on the plain of Nysa, gathering flowers. Many flowers grew there: roses, crocuses, beautiful violets, irises, hyacinths, and also the narcissus. The narcissus is a marvelous, radiant flower, admired by both the deathless gods and by mortal humans. From its root grow a hundred blooms, and it smells so sweet that all wide heaven above and the whole earth and the sea’s salt swell laughed for joy.

The narcissus grew there at the will of all-seeing Zeus, the god of loud thunder, the ruler of the other gods and goddesses. Zeus decided that Persephone was old enough to be married. He told Gaia, mother earth, to make the narcissus grow in the meadow to attract the attention of Persephone.

When Persephone saw the narcissus blooming, she was amazed by its beauty. She reached out with both hands to take the lovely flower. But to her surprise, the earth opened there in the middle of the meadow. Out of the yawning hole rode Hades, the Son of Cronos, the brother of Zeus, the god of the underworld — he who was called the Host of the Many because in the underworld were the spirits of everyone who had ever died.

Hades caught up the reluctant Persephone and carried her away. But before he could turn his horses to carry her back into the underworld, Persephone cried out shrilly, calling upon her father Zeus, Son of Cronos, who is the highest of all the gods and goddesses. She cried out, and the heights of the mountains and the depths of the sea rang with her immortal voice.

No one seemed to hear her cries — not one of the mortal human beings, not even the nearby olive trees, and almost none of the gods and goddesses. But two of the gods and goddesses did hear her. Sitting in her cave, tender-hearted Hecate, she of the bright hair, goddess of witches, heard Persephone cry out to Zeus. And from high above the earth from where he was guiding the sun across the sky, Helios, god of the sun, also heard Persephone cry out to Zeus.

At last Demeter heard Persephone’s cries. Bitter pain seized Demeter’s heart, and she tore the covering from her divine hair; her dark cloak she threw off her shoulders, and she sped towards where she had thought she had heard the cry; sped like a wild bird, over the firm land and yielding sea, seeking her child.

But she was too late. Persephone was beneath the earth. And when she asked where Persephone was, no one would tell her the truth, neither gods nor mortal human beings. For nine days, queenly Demeter wandered over the earth with flaming torches in her hands. Her grief was so great that she refused to eat the food of the gods, the ambrosia and the sweet draught of nectar. Then on the tenth day, Hecate, with a torch in her hands, came to give Demeter news.

“Queenly Demeter,” said Hecate, “O bringer of seasons and giver of good gifts, I do not know what god of heaven or what mortal man carried away Persephone and pierced your heart with sorrow. I heard her voice cry out, but I did not see who it was.”

Demeter sped swiftly with Hecate, holding flaming torches in her hands. Together, they came to Helios, who is watchman of both immortal gods and mortal humans, and stood in front of his horses.

“Helios,” said Demeter, “listen to me, goddess as I am, if ever by word or deed of mine I have cheered your heart and spirit. I heard the cry of my daughter, and though I could see nothing, the way she cried sounded as though someone had seized her violently. You look down from the bright upper air, and can see over all the earth and sea. Tell me truly, have you seen my dear child anywhere? Have you seen what god or mortal has violently seized her against her will, and against my will?”

“Queen Demeter,” Helios said, “I will tell you the truth, for I pity you in your grief. Zeus gave her to Hades, the god of the underworld, to be his wife. Hades seized her and took her in his chariot, loudly crying, down to his realm of mist and gloom.

“But cease your sadness and be not angry any longer,” Helios went on. “Hades, the Ruler of Many, is a fitting husband for your child. He holds great honor among the gods and goddesses, and he is appointed lord of all those among whom he dwells.”

Then Helios called to his horses, and drove his swift chariot around Demeter and Hecate, his horses moving like long-winged birds.

But after she heard what Helios had to say, Demeter’s her grief became more terrible and savage. She was so angry at Zeus, the dark-clouded Son of Cronos, that she stayed away from Mount Olympus where the other gods and goddesses gathered. She disguised herself, hiding her true form, and went to wander the towns and fields of humans. And none of the men or women who saw her knew that she was the goddess Demeter.

Source: Taken from the Homeric Hymn to Demeter. Our version of this story was adapted by Dan from a public domain translation of the Hymn from Hesiod: The Homeric Hymns and Homerica, trans. Hugh G. Evelyn-White (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1914), pp. 288-325. We also referred to a more recent translation, The Homeric Hymns: A Translation with Introduction and Notes by Diane J. Rayor (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), pp. 17-34.

Pronunciation guide

Demeter: deh MEE ter

Persephone: per SEH foh nee

Oceanus: oh kay AH nohs (soft “s” at the end)

Zeus: ZOOS (soft “s” at the end)

Gaia: GAI ah

Hades: HAY dees (soft “s” at the end)

Cronos: KROH nohs (soft “s” at the end”

Hecate: HEH kah tee

Helios: HEE lee ohs (soft “s” at the end)

Session One: Demeter and Persephone pt. 1

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story “How Persephone Disappeared.”

Read the story above.

III/ Act out the story.

Many of the children will have become familiar with the idea of acting out a story in previous Sunday school classes. This story is dramatic and lends itself well to acting out,

Ask the children who are the characters in the story, and perhaps have someone (you or one of the children) write them down. Ask who wants to act out the different parts (and note that you don’t have to be the same gender as the part you’d like to act out).

Now act out the story. Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with you; you will sit facing the stage.

Here’s the version of the story to the children act out — and notice that it is somewhat different from the version above:

Zeus, the ruler of all the other gods and goddesses, decided that Persephone should get married. Persephone was his daughter — he had been married to Demeter, Persephone’s mother, for a short time. Now Zeus was married to Hera, and he didn’t see Persephone very much, but he still had opinions about what Persephone should do. Since he was the ruler of all the other gods and goddesses, he didn’t bother asking Demeter or Persephone what they might want.

Zeus told Gaia, the goddess who was mother earth, to make a narcissus flower bloom at a certain spot where Persephone would be hanging out with her friends. Then he told Hades, who was the king of the underworld and Zeus’s brother, to be ready just below the narcissus.

Persephone was hanging out with her friends, the sea nymphs, and having a good time. Her mother, Demeter, wanted to spend a lot of time with her, and Persephone was glad to have some time with her friends. When she saw the narcissus flower blooming, she bent down to pick it. Then, out of nowhere, scaring her half to death, here comes Hades in his chariot — he grabbed her, and rode off down into the underworld. Persephone yelled in surprise, calling to her father, Zeus (for some reason she did not call out to her mother) as Hades whisked her below the earth.

Demeter wasn’t really paying attention, so she didn’t hear Persephone’s cries right away — only Hecate and Helios heard. But finally, Demeter realized that she had been hearing her daughter yelling for Zeus, and suddenly she realized Persephone was gone. She sped towards where she had heard the cries, but she was too late — Persephone was gone.

Demeter asked everyone who might know where Persephone had gone.

Hecate said that she had heard Persephone cry out, but that’s all she knew.

Helios said that he had seen the whole thing. Persephone’s father, Zeus, had decided she was old enough to leave her mother and be out on her own, so Zeus had decided to marry her off to Hades. After all, Hades was a great catch as a husband — he had a huge kingdom, since very dead human was his loyal subject, and besides he was very rich since he owned all the gold and silver and other minerals that were underground.

But what Helios had to say just made Demeter even more angry at Zeus. How dare he do this to her daughter! So she disguised herself, and went walking across the countryside….

III/ Think-pair-share: discussing the story

Get everyone back into a circle, and point out that this is a pretty strange and unpleasant story: two different parents who are clearly not talking to each other, and who have very different ideas for their daughter. We hear a lot about the parents are thinking in this story, but we don’t hear much about what Persephone is thinking. So here’s one question:

(1) When Hades grabbed her, why did Persephone yell out for her father, but not for her mother?

Ask the children to THINK for a few moments (maybe ten seconds at most) about how they would answer this question.

Now quickly PAIR up the children with the person next to them (if you have an odd number, there will be a group of three). Tell them to talk about their answers with their partners for a few moments (maybe fifteen to thirty seconds).

Now ask everyone to SHARE their own answer with the whole group. Repeat the question, and go around the circle, asking each child to give their answer.

Think-pair-share is a great technique for prompting reflection and discussion. Instead of the more extroverted and articulate children immediately calling out their answers to a question, think-pair-share provides a structure for all children to participate more equally, and perhaps to reflect a little more carefully before answering. A good summary of think-pair-share can be found at the following Web site — “ReadingQuest Strategies for Reading Comprehension: Think-Pair-Share.”

If you have time, here’s another question to ask:

(2) The story tells us a lot about what Demeter is thinking and feeling, but what do you think is Persephone thinking and feeling?

Again: Ask the children to THINK for a few moments (maybe ten seconds at most) about how they would answer this question.

Now quickly PAIR up the children with the person next to them (if you have an odd number, there will be a group of three). Tell them to talk about their answers with their partners for a few moments (maybe fifteen to thirty seconds).

Now ask everyone to SHARE their own answer with the whole group. Repeat the question, and go around the circle, asking each child to give their answer.

IV/ Conversation and optional snack

Think-pair-share is a great way to help every child participate in a structured conversation. If you have time, you may wish to extend the conversation in a less formal manner. Here are two more questions you and the children may enjoy talking over:

— Why do you think Hades felt the need to steal Persephone away so he could marry her, rather than going to her directly and trying to get her to fall in love with him? Do you think he was ashamed of being the god of the dead? Or maybe, because he was so powerful, he had become arrogant, and thought he could do whatever he wanted (as long as his more powerful brother Zeus approved)?

— Who has more power in this story, the gods or the goddesses?

If you decided to have a snack, you can have one of the children pass out snack while you start this conversation.

VI/ Free play

If you need to fill more time, you could play a game of some kind (if this is the first week your group is together, try a name game). Just make sure you have everyone come together for a closing circle before you’re done.

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about Persephone, right? What happened in the story? What was Persephone thinking and feeling?” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

End by saying together some closing words. Here are some sample closing words, which we posted in the classroom where everyone could see them:

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

Then before you all go, tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (assuming that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

Leader resource

Feminism and the myth of Persephone

“I suggest that the only way we can, as human beings, integrate ourselves into a life-sustaining relationship with nature, is for both males and females to see ourselves as equally rooted in the cycles of life and death and equally responsible for creating a sustainable way of life.” — Rosemary Radford Ruether (1)

One obvious point of this lesson is to provide a feminist perspective on this familiar myth. Since the ancient Greek myths so often have male protagonists and/or a male point of view, feminist interpretations often ask what the women in the myths might have thought and felt.

Why should we care about this? The theologian Rosemary Radford Reuther believes that the roots of our contemporary environmental crisis lie, in part, in the historic domination of women by men. Men dominated women in Western culture for many centuries, and domination came to be seen as a natural state of affairs. Thus, it came to be seen as “natural” for human beings to dominate other living beings — just the way human men dominate human women. So, Reuther argues, we have to stop thinking in terms of one living being dominating another living being. When we start asking ourselves what women in ancient Greek myths thought and felt, we are thinking our way out of destructive domination.

With the children, you can help them think through the roles of males and females in these stories. As they think about this, we hope they begin to see how gender roles where one gender dominates another gender are unfair and unwise.

Note:

(1) Rosemary Radford Ruether, Goddesses and the Divine Feminine: A Western Religious History (Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2005), p. 40.