From Many Lands

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2020 Dan Harper

4. The Foolish Little Tree Spirit

One day, a group of Buddha’s followers was sitting in the Hall of Truth talking. They were talking about some of the others: Kokālika was friends with Sāriputta and Moggallāna, but the three friends just couldn’t get along together. Just that day, Kokālika had asked his two friends to travel with him back to his own home town, even though he knew they were busy; and they of course had refused — rather rudely, too. Kokālika couldn’t let it rest there and just had to tell them how disappointed he was. The result was a loud argument among the three of them.

Buddha came and and heard his followers talking about the three friends. One of the followers said, “Sāriputta and Moggallāna are always arguing with each other, and Kokālika always says something foolish.”

“That reminds me of a story,” said Buddha, and he told his followers this tale:

———

Once upon a time, two tree-spirits lived in a forest. One of the tree-spirits lived in a small, modest tree; the other tree-spirit lived in a huge old tree that towered over the other trees.

Now in that same forest there lived a ferocious tiger and a fearsome lion. This lion and this tiger used to kill and eat every large animal they could get. Because of this, no human beings dared set foot in the forest, nor were there very many other animals left. Worse yet, the lion and the tiger were very messy eaters, leaving chunks of meat on the forest floor to rot. The whole forest was filled with the smell of their rotting food.

The smaller tree-spirit had no common sense, and got the idea that the lion and the tiger had to leave the forest. He said to his neighbor, the great tree-spirit, “I have decided to drive the ferocious tiger and the fearsome lion out of our forest!”

“My friend,” said the great tree-spirit, “don’t you see that it is because of these two creatures that our beloved forest is protected? If the tiger and the lion leave the forest, human beings will come into our home and cut all us trees down, turning the forest into farms.” And the great tree-spirit recited part of a poem:

When you feel a friend

Might end your peace of mind:

Be wise, unwind your thoughts,

And guard your actions well.

That same friend may increase

The peace you find in life:

Let your friend’s life be yours, and

That friend be dear to you.

But the little tree-spirit didn’t listen to the great tree spirit, and the very next day assumed the shape of a large and terrible monster, and drove the ferocious tiger and the fearsome lion out of the forest.

Within two weeks, the human beings who lived close by began to realize that the tiger and the lion had left for good. They moved into the forest, and cut down half the trees. The little tree spirit was frightened, and cried out to the great tree spirit, “Oh, you were right, I should never have driven the tiger and the lion out of our forest, for now the human beings are cutting us down. Oh, great tree spirit, what can we do?”

“Go find the tiger and the lion and invite them to return to the forest,” said the great tree spirit. “That is our only hope.”

The little tree spirit ran off and found the tiger and the lion living nearby. He greeted them, and said, “Lion and Tiger, do come back to live in the woods once again, for without you the human beings cut down the trees, and soon the woods you lived in will be gone for good.”

But the tiger and the lion just growled at the little tree spirit, and rudely said that they would never return. Within a few days, the human beings had cut down the rest of the trees, and the forest was gone.

———

When Buddha finished telling the story, he smiled and said, “As you might have guessed, the foolish little tree spirit in the story is Kokālika, the lion is Sāriputta, and the tiger is Moggallāna.”

The followers nodded, and one of them said, “And you, Buddha, are the great tree spirit in the story.”

SESSION 4: “The Foolish Little Tree Spirit”

Top-level educational goals:

(1) Have fun and build community;

(2) Increase religious literacy;

(3) Build skills associated with liberal religion, e.g., interpersonal skills, introspection, basic leadership, being in front of a group of people, etc.

Educational objectives for this session:

(1) Get to know other people in the class;

(2) Hear a story from this religious tradition;

(3) Be able to talk about one or more incidents or themes from the story, e.g., if parents ask what happened in Sunday school today.

Preparation for optional hand puppet activity

Print out the patterns for the paper bag hand puppets on card stock. Carefully cut along the lines, so the children can trace the outside of the card stock pattern. OR you can help the children draw the puppet pieces freehand.

Tree Spirit puppet patterns (PDF)

Assemble supplies:

glue sticks

scissors

pencils

black magic markers

paper bags (lunch bag size, 5 x 10 in. folded)

paper or card stock in the following colors:

—pink (for noses and mouths)

—white (for eyes)

—dull green (for Little Tree Spirit)

—bright green (for Great Tree Spirit)

—orange (for Tiger)

—yellow (for Lion’s head)

—brown (for Lion’s mane)

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story

Read “The Little Tree Spirit” to the children.

III/ Act out the story.

IF YOU DO NOT HAVE TIME to prepare to make paper bag puppets, then the children can act out the story with their bodies, just as they have been doing for the past three weeks. Simply follow the directions for acting out the story in the first session plan.

IF YOU ARE ABLE TO MAKE PUPPETS, this week’s story is fairly short to allow you the additional class time you will need to make the puppets.

III-a/ Making the puppets

Make sure you have all the supplies you need (see “Optional advance preparation”).

To act out the story, you will only need to make four puppets, one of each character. If you have two or three children, you can all make the puppets together as a group. With more children, you can split the group in two, with one adult in each group, and each group can make two puppets. With even more children, you can show the process for making one puppet, then split the children into small groups; each group will be assigned to make one puppet (and you will make more than one of some of the puppets); and adults circulate from one group to another helping and supervising.

How to make the puppets:

Let’s start by seeing how the Tiger puppet is made.

Step One:

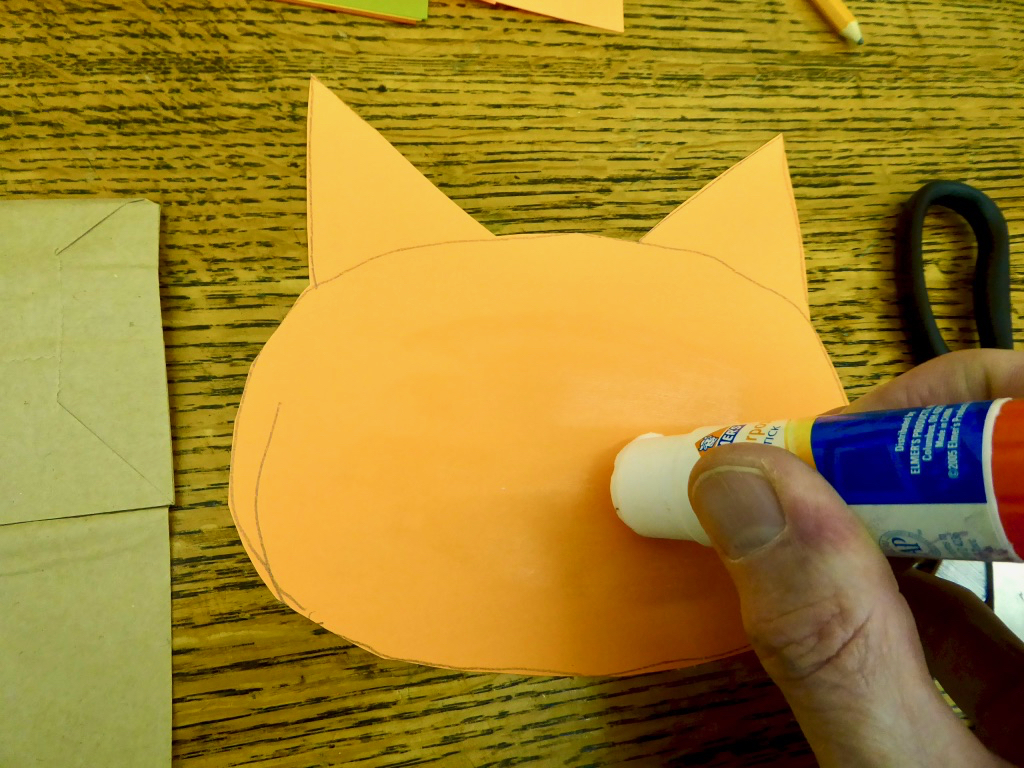

Trace the head pattern onto a piece of orange paper, and cut out the head (it’s also fine to draw the head shape freehand on the paper, using the pattern as a guide to size and shape).

Then glue the head onto what is usually the bottom of the paper bag.

Step Two:

Using the patterns, trace and cut out two eyes from white paper (you can also trace around the cap to a glue stick). Trace and cut out one nose from pink paper. Glue the eyes and nose onto the head shape.

Use the black magic marker to draw pupils in the eyes, stripes on the head, and whiskers as shown:

Step Three:

Trace and cut out the mouth shape from pink paper. Fold it about one third of the way across the diameter (about one inch from the edge). Then glue the mouth in the flap formed by the bottom of the paper bag where it’s folded over. You want a little bit of the pink mouth to show below the head of the puppet.

Here’s a photo of the completed puppet, with a hand inside:

The rest of the puppets are made in much the same way.

For the Lion: Use the same head pattern as for the Tiger, but cut the head out of yellow paper. Cut a mane out of brown paper and glue the head on the mane. Glue the head with its mane onto the paper bag. Glue on the eyes and draw in the pupils. Glue on the nose. Glue in the mouth.

For the Little Tree Spirit: Use the tree pattern and cut the tree out of green paper. Glue the tree shape onto the paper bag. Glue on the eyes and draw in the pupils. Glue in the mouth.

For the Great Tree Spirit: Use the mane pattern but cut the shape out of green paper. Glue the resulting large tree shape onto the paper bag. Glue on the eyes and draw in the pupils. Glue in the mouth.

Here are the four completed puppets:

III-b/ Acting out the story with puppets

The easiest way to set up a puppet stage is to have the puppeteers crouch behind a table. Set up chairs for the audience on the other side of the table from the puppeteers.

If you print out the backdrop, put the table near a wall, and attach the backdrop to the wall, positioned so the puppets will appear in front of them. (It’s a pretty simple design, and you and the children could easily draw and color in your own backdrop.)

Once you’ve set up the stage, and you have the puppeteers in place, the lead teacher reads the story again, prompting the puppeteers where necessary to act out the story.

If you have a lot of children, and more than one set of puppets, there’s a good chance that those who made each set of puppets will want to act out the story with their puppets. It’s a short story, so you should have time to have more than one puppet show.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group. Go over the story to make sure the children understand it. You might want to give them some of the back story — that in real life, Sāriputta and Moggallāna were wise and trustworthy but always argued with each other, while Kokālika wasn’t wise or very nice and talked too much.

Now ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

Ask some questions that might help the children think about the story:

“Do you know anybody like Sāriputta and Moggallāna, who are friends and good people but who argue with each other all the time?” and “If so, what’s it like to spend time with them? Are they annoying?”

You could also use this prompt for discussion:

“Some people say we should get rid of all the meat-eating animals like lions, tigers, bears, wolves, foxes, and so on — just like the Little Tree Spirit says in the story. Yet we know that we need those big meat-eating animals, because they help keep the balance of nature, right?” Most of the children will probably know this already, but if this is a new concept to any of them, help them understand the balance of nature.

Note that some contemporary Buddhists interpret this story as a story about how to care for the environment; see Leader Resources below.

Above: The Little Tree Spirit puppet and the Lion puppet in front of the backdrop

VI/ Free play

If you don’t have time to do the preparation for the paper bag puppets, just have some free play time. Free play can help the class meet the first educational goal, having fun and building community. Ideas for free play: free drawing; “Duck, Duck, Goose”; play with Legos; walk to playground or labyrinth (if time); etc.

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about the Little Tree Spirit, who didn’t like the Lion and Tiger who were messy eaters.” As always, you’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If you’re sending puppets home with children, remind them what each character did in the story.

Say the closing words together — either these words, or others you choose:

Go out into the world in peace

Be of good courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return no one evil for evil

Strengthen the fainthearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Rejoice in beauty

Speak love with word and deed

Honor all beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

Post some of the completed paper bag puppets on the bulletin board before you go.

LEADER RESOURCES AND BACKGROUND

1. Source of the story

Adapted from Tale 272, Vyaggha-Jātaka, from the Cowell translation of the Jataka tales (1911).

2. Ecological interpretation of this story

This story has been interpreted as an environmental justice story. Here’s one such interpretation, from an essay by Christopher Key Chapple, “Animals and the Environment in the Buddhist Birth Stories,” in Mary Evelyn Tucker and Duncan Ryuken Williams, ed., Buddhism and Ecology: The Interconnection of Dharma and Deeds, vol. 1 in the Religions of the World and Ecology series, (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ., 1997), pp. 141-142:

“[Another Jataka tale] with an underlying ecological theme is the Vyaggha-Jātaka, a tale reminiscent of Aldo Leopold’s concept of ‘thinking like a mountain.’ In this story, the Buddha dwelt in the forest as a tree spirit. In this particular forest also lived a lion and a tiger, who use to ‘kill and eat all manner of creatures,’ leaving behind their offal to fester and decay. Because of the ferociousness of these predators, no humans dared to enter the forest, let alone cut down even a single tree. However, one of the tree spirits could not stand the stench generated by the lion’s and tiger’s rotting victims. One day, against the advice of the Buddha-tree, the spirit assumed an awful shape and scared off the killers. The people of a nearby village noticed that they no longer saw the tracks of either the lion or the tiger and began to chop down part of the forest. Despite the entreaties of the foolish tree spirit, the animals would not return, and after a few days the [humans] ‘cut down all the wood, made fields, and brought them under cultivation,’ thus driving out the spirits of the forest.

“The moral given by the Buddha was that one should recognize that one’s peace sometimes depends on being able to stave off the incursion of others, and and that one should not disturb such a state of affairs. From an environmental perspective, the presence of predators maintained an acceptable balance within the ecosystem, a balance that could not be restored after the predators were driven off, opening up the land for clear-cutting and agricultural use.”

I would like to suggest another key message in this story: We must look at environment, not from the perspective of our individual desires, but as a system that includes many sentient beings; and some of those other sentient beings are going to have desires that directly conflict with our desires.

This leads to another conclusion, that may be more relevant to middle elementary children: When we try to impose our own personal desires on everything else, it generally does not turn out well for anyone.

Middle elementary children are in the process of understanding how being selfish can wind up harming them, and this story may help extend this growing understanding further.

3. Background of the characters

According to Buddhist tradition, Kokālika is a foolish character who tends to get himself in trouble because he talks too much. He appears as other foolish characters in other Jataka tales — including, most famously, the talkative tortoise who agrees to be flown to the Himalayas by two friendly birds, with his mouth grasping a stick that the two birds carry so they can fly with him; the tortoise comes to a bad end when he can’t resist talking, and in doing so loses his grasp on the stick, and falls to his death (Jataka 175).

More seriously, Kokālika is said to have approached the Buddha when the Buddha was growing old, to suggest that he be put in charge of the Buddhist community. But the Buddha rejected this proposal, saying that he would not give leadership of the community even to Sāriputta or Moggallāna, the two wisest and most trustworthy disciples, let alone to someone as foolish as Kokālika (this event is referred to in the Buddhist scripture known as the Abhayarājakumāra Sutta).

Sāriputta or Moggallāna, by contrast, were known as wise, among the wisest of the disciples of Buddha. Yet, according to tradition, the two of them could not get along.