From Many Lands

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2019 Dan Harper

1. SPIDER AND NZAMBI MPUNGU’S HEAVENLY FIRE

First you must understand who Nzambi Mpungu is. He is the father of all things, and lives a happy life above the sky, where he has a many wives and beautiful children. He spends very little time thinking about us people here on earth, and since he is a good being there is no use in offering him worship or sacrifices. True, there are lesser gods and goddesses who can hurt us people here on earth, and to them we might offer worship and sacrefice, but Nzambi Mpungu will not mind, for he is not in the least jealous.

Now you may question whether Nzambi Mpungu actually exists. But there is a man still living, near the town of Loango, who says that one day, when it was thundering and lightning and raining very heavily, and when all the people in his village, being afraid, had hidden themselves in their houses, he alone was walking about. Suddenly, and at the moment of an extraordinarily vivid flash of lightning, after a very loud peal of thunder, he was seized and carried through space until he reached the roof of heaven, when it opened and allowed him to pass through to where Nzambi Mpungu lives. There the man met Nzambi Mpungu, who cooked some food for him, and then showed the man his great plantations and rivers full of fish. Then Nzambu Mpungu left the man, telling him to help himself whenever he felt hungry. The man stayed there two or three weeks, and never had he had so much good food to eat. At last Nzambi Mpungu came to him again, and asked the man whether he would like to remain there always, or whether he would like to return to the earth. The man said that he missed his friends, and would like to return to them, and Nzambi Mpungu sent him back to his family. So you see, Nzambi Mpungu does indeed live above the sky.

Nzambi, on the other hand, is Mother Earth. Some say she is Nzambi Mpungu’s first child. She is the great princess, a mighty ruler who governs all on earth. She has the spirit of rain, lightning, and thunder for her own use. She is a stern judge, and a fearsome ruler.

Now we can begin the story of how Spider almost married Nzambi’s daughter.

For Nzambi had a most delightful daughter whom anyone would have wanted to marry. But Nzambi swore that no earthly being should marry her daughter, unless they could bring her the heavenly fire from Nzambi Mpungu, who kept it somewhere in the heavens above the blue roof of sky.

The people all wondered who could ever bring the heavenly fire down to earth.

Then Spider said, “I will bring the heavenly fire to earth, but I will need help.”

“We will gladly help you,” said all the people, “if you will reward us for our help.”

So Spider climbed up to the blue roof of heaven, and dropped down again to the earth, leaving a strong silken thread firmly hanging from the roof to the earth below. Then he called to Tortoise, Woodpecker, Rat, and Sandfly, and bade them climb up the thread to the blue roof of sky.

When they got there, Woodpecker pecked a hole through the roof, and through this hole they all entered into the realm of Nzambi Mpungu, who, as it happens, was very badly dressed. Nzambi Mpungu received them courteously, and asked them what they wanted up there.

“O Nzambi Mpungu of the heavens above, great father of all the world,” they said, “we have come to fetch some of your heavenly fire, to bring it down to Nzambi who rules upon earth.”

“Wait here then,” said Nzambi Mpungu, “while I go to my people and tell them of the message you bring.” But Sandfly followed Nzambi Mpungu without being seen, and heard all that was said. While Sandfly was gone, the others talked among themselves, wondering if it were possible that someone who went around so badly dressed could be so powerful.

At last Nzambi Mpungu returned to them. “My friend,” he said to Spider, “how can I know that you have really come from the ruler of the earth, and that you are not impostors?”

“Nay,” said Spider and all the others, “put us to some test so we may prove our sincerity to you.”

“I will,” said Nzambi Mpungu. “Go down to this Earth of yours, and bring me a bundle of bamboos, so I can make myself a shed.”

Tortoise climbed all the way down to Earth, leaving the others where they were, and soon returned with the bamboo.

Nzambi Mpungu then said to Rat, “Get beneath this bundle of bamboo, and I will set fire to it. If you escape I shall surely know that Nzambi sent you.”

Rat did as he was told, and hid under the bundle of bamboo. Nzambi Mpungu set fire to the bamboo, and lo! when it was entirely consumed, Rat came from amidst the ashes completely unharmed.

“Ah!” said Nzambi Mpungu. “You are indeed sent from Nzambi on Earth. I will go and consult my people again.”

Spider, Rat, Woodpecker, and Tortoise sent Sandfly after him once again, bidding him to keep well out of sight, to hear all that was said, and if possible to find out where the lightning was kept. Sandfly soon returned and told them all that he had heard and seen.

When Nzambi Mpungu came back a little later, he said, “Yes, I will give you the heavenly fire you ask for. But only if you can tell me where it is kept.”

Spider said, “Give me then, O Nzambi Mpungu, one of the five cases that you keep in the hen-house.”

“Truly, you have answered me correctly, O Spider!” said Nzambi Mpungu. “Take this case, and give it to your Nzambi.”

Tortoise carried the heavy case containing the heavenly fire down to the earth. When they got to Nzambi’s house, Spider presented the fire from heaven to her. True to her word, Nzambi agreed to let Spider marry her delightful daughter.

But Woodpecker grumbled, saying, “Surely your daughter is mine, for I was the one who pecked the hole through the roof, without which the others never could have entered the kingdom of the Nzambi Mpungu.”

“No, she is mine,” said Rat. “For I risked my life among the burning bamboo.”

“Nay, O Nzambi, she is mine,” said Sandfly. “For without my help the others would never have found out where the fire was kept.”

And Tortoise complained that he was the one who had to return to Earth to fetch the bamboo, and then had to carry the heavy case down to Earth, so of course the daughter should be married to him.

After listening to them all, Nzambi said: “Nay, Spider was the one who planned how to bring me the heavenly fire, and he has indeed brought it. By rights, my daughter should be married to him. But I know you others will make her life miserable if I allow her to marry Spider. Since she cannot marry all of you, I will not allow her to marry any of you. But I will give you her value” — for the people Nzambi ruled customarily gave presents when one of their children married.

Nzambi then paid fifty bolts of cloth each to Tortoise, Rat, Woodpecker, Sandfly, and Spider.

As for the daughter, she never married, and had to wait on Nzambi for the rest of her days.

Above: Nzambi Mpungu, from a sculpture by an African artist of the early 20th century; the artist was a follower of the Kongo religion (the Kongo religion is related to several religions in the Americas including Haitian Vodoun and Brazilian Candomblé). Sculpture in the Musée Royal de l’Afrique Centrale, Bruseels, Belgium.

SESSION ONE: “Spider and Nzambi Mpungu’s Heavenly Fire”

Top-level educational goals:

(1) Have fun and build community;

(2) Increase religious literacy;

(3) Build skills associated with liberal religion, e.g., interpersonal skills, introspection, basic leadership, being in front of a group of people, etc.

Educational objectives for this session:

(1) Get to know other people in the class;

(2) Hear a story from this religious tradition;

(3) Be able to talk about one or more incidents or themes from the story, e.g., if parents ask what happened in Sunday school today.

Optional advance preparation:

If you’re stuck for time, you can teach this class with only a few minutes preparation. If you have time to do advance preparation:

a. Print out copies of the Nzambi Mpungu coloring page (PDF)

b. Make the Kisolo games as described on this: How to play (and make) Kisolo (PDF)

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story “Spider and Nzambi Mpungu’s Heavenly Fire”

Read the story above.

If you would like to give the children something to do while listening to the story, print out the Nzambi Mpungu coloring page (PDF).

III/ Act out the story

As usual, we will help the children internalize the story by acting it out. Some of the children may be familiar with how to act out a story, but others won’t be. This is a simple story to act out, and a good way to help the class (children and adults!) build the skills needed to act out a story.

Ask: “Who are the characters in this story?” In this story, the main characters are Nzambi, Nzambi Mpungu (make sure the children understand the difference between the two deities!), Spider and the other animals, the villagers. With all the Villagers, there is a role for everyone!

Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with the lead teacher; you will sit facing the stage.

The lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. Actors do not have to repeat dialogue, although some of them will want to do so. The lead teacher may wish to simplify the story on the fly, to make it easier to act out.

Fill the bulletin board in your classroom! It would be great to take photos, print them out later, and post them on the bulletin board in your classroom.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group. Now ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own. Make sure the children understand the difference between Nzambi, who is a mother-earth-type goddess, and Nzambi Mpungu, who is a transcendent god.

One of the most interesting elements in this story is that the most important god, Nzambi Mpungu, really doesn’t care much about human beings or other animals who live on earth. He will only give the heavenly fire to Spider and the others when he determines that they truly have come from Nzambi — in other words, Nzambi Mpungu pays attention to what the lower gods and goddesses think, but he doesn’t care much about mortal beings. Ask the children what they think of this — should the most powerful god pay attention to humans? — if so, why? Or should the most powerful god ignore humans? — and if so, why?

Next you might ask how true this story is. Ask the children: “Is this story really true, is it partly true, or is it completely made up and more like a fairy tale?” Most of them will say this story is more like a fairy tale. “If this story is more like a fairy tale, does it have a moral?” Some of the children might say that the moral is cooperation, or something along those lines; however, the author of this curriculum sees this story as morally ambiguous. The characters in the story behave well at times, badly at other times, and it is hard to draw a consistent moral message out of it.

You may want to ask: “Is Spider a good character, a bad character, or something in between?” Review the various things Spider does, and decide which of Spider’s actions are good, which not so good.

“So what is the point of the story?” The children may have creative responses well worth listening to. When they are done, you can suggest that this story tells us a LOT about the relationship between mortal beings who live on earth, gods/goddesses who live on earth, and the god who lives beyond the sky, Nzambi Mpungu. Maybe that’s the whole point of the story.

V/ Playing Kisolo

If you have the Kisolo game boards and pieces, the children can play the game. Explain that this game is a traditional game in the Congo, where the story comes from — probably Spider and his friends played this game together.

How to play Kisolo

Kisolo is a Congolese variant of the widespread Mancala-type games. These are simplified rules, designed so you can play a game in fifteen minutes or so.

To make a Kisolo board: Take two egg cartons, and cut their lids off. Tape them together to make a game board with six by four holes. (Most traditional Kisolo boards are four by seven holes in size, but a smaller board is allowable and makes for shorter game play.) You can also use the commercially available Mancala boards — take two of them, place them side by side and ignore the larger bins at the ends of the boards.

To set up the board: Place three seeds in each bin. You can use actual bean seeds (dried Lima beans work best because they’re large), or small glass tokens or what-have-you, for seeds.

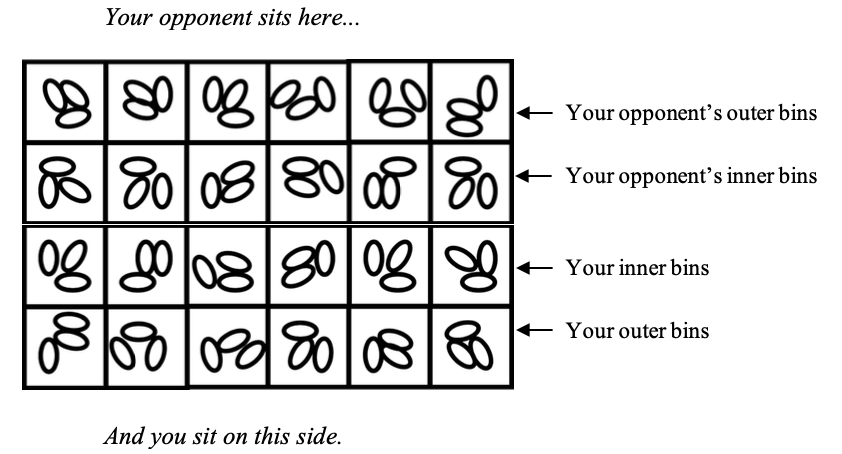

To start: Two players sit at the long sides of the game board opposite each other. The twelve bins on your side belong to you, and the twelve bins on your opponent’s side belong to them. Each player has six “outer bins” (the row of bins nearest to them) and six “inner bins” — see the diagram.

To play: Youngest player starts.

When it is your turn, see if one of your inner bins contains seeds AND your opponent’s inner bin opposite it contains seeds. (If that’s true of more than one of your inner bins, just pick one; OR if you can’t capture any seeds, see below.)

Then remove all the seeds from your inner bin, plus the seeds in the corresponding bin that belongs to your opponent, and any seeds in your opponent’s outer bin that’s next to that inner bin.

Now “sow the seeds,” that is, starting with the inner bin you’ve just emptied, place one seed in each of your bins and continue counterclockwise sowing seeds only into your bins, until you have sown all the seeds.

If your last seed falls in one of your inner bins, then you ALSO get to remove all the seeds from your inner bin, plus the seeds in the corresponding bin that belongs to your opponent, and any seeds in your opponent’s outer bin that’s next to that inner bin. Then you sow the seeds as before — it’s like you get another turn (but after that your turn is over).

IF YOU CANNOT CAPTURE ANY SEEDS, then empty the seeds out of any one of your bins and sow those seeds counterclockwise into your own bins.

To win the game: Capture all the seeds in your opponent’s INNER bins (doesn’t matter how many seeds are in the OUTER bins). Note that some games will end in a draw, where neither player can win — if it feels like the game is going nowhere, the players can agree to a draw.

Above: A Kisolo board made out of two egg cartons fastened together with a glue gun. You can glue decorative squares as shown, if you like. (Depending on the egg cartons, you may have to glue popsicle stick reinforcements on the underside of the game board.)

VI/ alternate activity/ Free play

If you need to fill more time, have some free play time. Free play can help the class meet the first educational goal, having fun and building community. Ideas for free play: free drawing; “Duck, Duck, Goose”; play with Legos; walk to playground or labyrinth (if time); etc.

VII/ Closing circle

When time is almost up, have the children stand in a circle by touching toes, or touching elbows.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about Spider and Nzambi Mpungu, right? Anyone remember the difference between Nzambi and Nzambi Mpungu?” — etc. You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

Say the closing words together — either these words, or others you choose:

Go out into the world in peace

Be of good courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return no one evil for evil

Strengthen the fainthearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Rejoice in beauty

Speak love with word and deed

Honor all beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

LEADER RESOURCES AND BACKGROUND

1. Source of the story

Adapted from Richard Edward Dennett, Notes on the Folklore of the Fjort (French Congo), London: Folk-lore Society, 1898, pp. 74-76 and 131-135.