From Long Ago

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper, v. 2.0

Copyright (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

The Birth of Confucius

Once upon a time, some two thousand five hundred years ago, in a city in China called Tsou, there lived a man named Kong He. He had been a soldier, though he was now long since retired, and he was so very tall that some people claimed he was at least ten feet tall.

At the time of this story, Kong He was seventy years old. His first wife had died, leaving him the father of nine daughters. Kong He loved his daughters, but he had always hoped to have a son. So one day he went to the head of the noble house of Yan, and asked for one of their daughters in marriage. The youngest daughter, Yan Zhengzai, said that she would be willing to marry this older man. And so the two were married.

Not long after the marriage, Yan Zhengzai traveled to Mount Ni. This was a sacred mountain that Emperor Shun had dedicated to the worship of its guardian spirit. There Yan Zhengzai offered up prayers, hoping that she might give birth to a boy-child. That night, she dreamed that a spirit came to her and said, “You shall have a son, who will be a great sage and prophet, and you must bring him forth in the hollow mulberry tree.”

Not long after this dream, Zhengzai did indeed become pregnant. One day while she was pregnant, she was resting and while she was resting five old men came up to her, leading behind them a Qilin, or Chinese unicorn, which is the size of a small horse, has one horn, and is covered in scales. The Qilin carried in its mouth a tablet made of green jade. On the tablet was carved a prophecy: “The son of the essence of water shall soon succeed to the withering Zhou, and be a throneless king.” Zhengzai tied a silk scarf around the Qilin’s horn, upon which the animal disappeared. She was not sure whether she had been asleep and dreaming, but she was sure what the prophecy meant: her baby would grow up to become wise and valued leader, even though he would never hold political office.

Soon it came time for Yan Zhengzai to give birth. She told her husband that she must give birth in the “hollow mulberry tree,” wherever that was. Kong He said that there was a dry cave in a hill nearby named “The Hollow Mulberry.” Quickly they travelled to this dry cave so that the words of the spirit would be true, and her child would be born in a hollow mulberry tree.

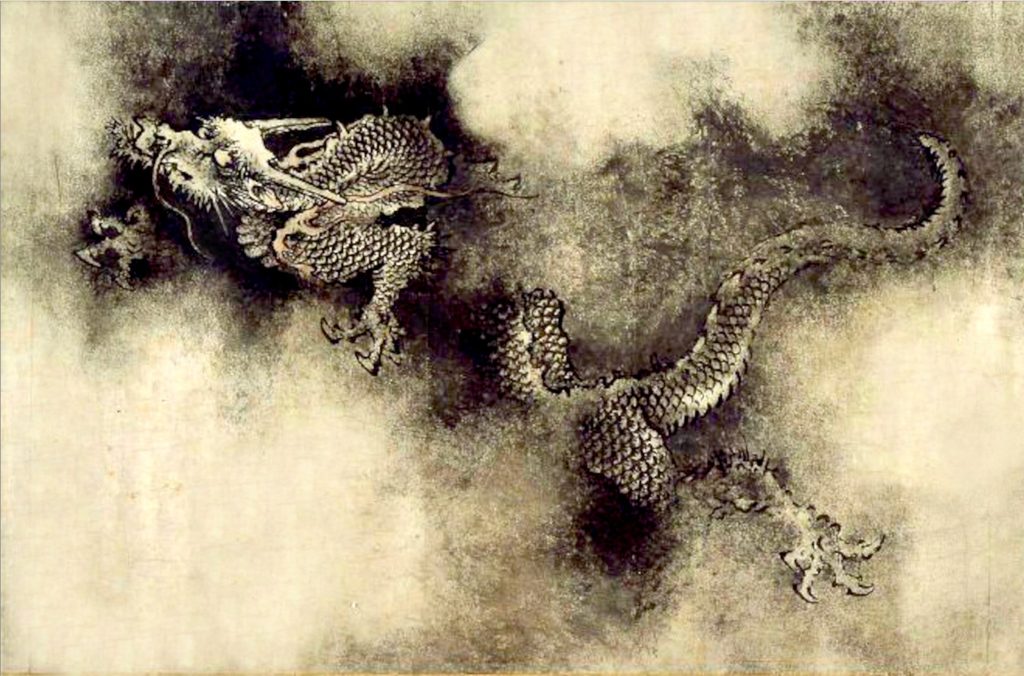

The child was born that very night. And as the child was born, two good and wise dragons appeared in the sky to keep watch, one to the right of the hill where the cave was, the other to the left of the hill. Then two spirits appeared in the air above the hill, two women who poured out fragrant drafts, as if to bathe Yan Zhengzai in beautiful aromas as she was giving birth.

Within the cave, Zhengzai heard music, and a voice saying to her: “Heaven is moved at the birth of your son, and sends down harmonious sounds.” A spring of water bubbled up within the dry cave, so that Zhengzai could bathe her new baby. This also confirmed the prophecy that the new baby was the “son of the essence of water.”

After the baby was born, five old men came from afar to pay their respects to the new baby. Some people said they were the five old men of the sky, the five immortals who never die, and they had come down from the five planets to celebrate the birth of this great child.

Kong Qiu, the baby, grew up to be a great human being, a prophet and sage who was known as Kong Fuzi, or Teacher Kong. In the Western world, he became known as Confucius.

Kong Fuzi said that by the age of fifteen, he knew that he wanted to spend the rest of his life learning how to master one’s own self, and learning how we can live harmoniously with brothers and sisters, with our parents and children, with all those with whom we come into contact. He learned these things, and he began to teach others how to live wisely and well. Confucius grew so famous that leaders of nations invited him to come and teach them how to govern their nations fairly and wisely. Even today, some two thousand five hundred years after he was born, millions of people around the world still follow his teachings.

Photo: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic by Daniel Vaulot; edited for clarity.

Sources:

Confucius, the Great Teacher: A Study, by George Gardiner Alexander. pp. 33 ff.

The Chinese Classics: Life and teachings of Confucius, vol. 2, trans. James Legge, p. 58; and p. 58 footnote.

Confucius: His Life and Thought, by Shigeki Kaizuka (Dover reprint, 1956/2002), pp. 42-44.

Sages and filial sons: mythology and archaeology in ancient China, by Julia Ching and R. W. L. Guisso (Chinese University Press, 1991), p. 143.

The dragon, image, and demon: The three religions of China: Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism, by Hampden C. DuBose (New York: A.C. Armstrong, 1887), pp. 91-92.

Session Three: The birth of Confucius

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story

Read the story above.

III/ Act out the story

By now the children should be getting pretty good at acting out stories.

Ask: “Who are the characters in this story?” There are some great characters in the story, including K’ung Ho (Confucius’ father); Yan Zhengzai (his wife), the baby Kong Qiu, the Qilin (unicorn), the Dragons, the Five Old Men, etc. In addition, there is a Voice from the Sky, which could be everyone who doesn’t take one of the other roles. It is important to tell the children that Chinese dragons are not like Western dragons. While Western dragons are often bad or evil, hoard gold, and kill people, Chinese dragons are good, and wise, and omens of good fortune.

Determine where the stage area will be, and the lead teachers sits facing the stage. As usual, the lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. Depending on the size of the class, some children make take on more than one role (e.g., the Unicorn could also be a Dragon, and a Dragon could be one of the Five Old Men). Also, feel free to assign parts regardless of gender.

Children tend to like this story, so you may want to act it out twice, with different sets of lead actors each time.

Once again, it would be great to take photos, print them out later, and post them on the bulletin board in your classroom.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group. Go over the story to make sure the children understand it.

Now ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

Ask some questions specific to the story: “How does is this story like the Christmas story of the birth of Jesus?” (Even though the story of the birth of Jesus is very much a part of popular culture, you may want to review it with the children, emphasizing miracles like the angel that tells Mary she will give birth to a boy, the friendly animals in the stable, the angels which appear to the shepherds, the Wise Men who bring gifts). “How true is this story — really true, sort of true, mostly made up but feels true, or what?” (Expect a range of answers for this last question.)

I like to tell children that while this story isn’t really true, because we know there are no such things as unicorns and dragons, there is truth in it. Confucius was one of the greatest people who ever lived, and so we like to imagine that there must have been miracles that happened when he was born. And, if you think about it, any time a child is born, it feels like a miracle — a whole new life has just started, and we can watch that baby grow up into a child, then a teenager, then an adult — it’s a miracle that a baby can do that!

V/ Drawing pictures and having snack

This is another great story to draw pictures of. You can find one artist’s idea of what the dragons and the four old men looked like below.

For U.S. children who may not be clear that there are different kinds of dragons, I’ve included an image of a Chinese dragon below (click on the image below for a larger version). This is from the Nine Dragons scroll by the Chinese artist Chen Rong, and was painted in the year 1244 C.E. (Public domain image from Wikimedia Commons.) Note the horns, and the absence of wings. Also, notice the benign expression: Chinese dragons are good, while Western dragons often are not at all good.

VI/ Free play

Ideas for free play: “Duck, Duck, Goose”; play with Legos; if weather is warm enough you might want to go out to the front play area; etc.

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about the miraculous birth of Confucius.” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

Say the closing words together — either these words, or others you choose:

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.