From Long Ago

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper, v. 2.0

Copyright (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

Chang Kung’s Secret

The Emperor Kangxi was the fourth emperor of the Qing dynasty in China. Before he became the emperor, the land of China had been torn by wars. During the wars, the people had to leave their farms to fight, and farms were destroyed in battles. But after Kangxi became the emperor, there was peace throughout the land. The people could tend to their farms, and so there was plenty of food for everyone. So it was that Kangxi ruled over a land of peace and plenty.

When he was old, Emperor Kangxi began to think about what would happen to China after he died. What principles, what rules could he give to the next emperor so that China would continue to be a land of peace and plenty? He wanted to write down the principles for peaceful rule. And he remembered something that had happened many years before.

One year, not long after peace had been established throughout the land, Emperor Kangxi went on an Inspection Tour, a journey across all of China so that he could see that all was peaceful, and that the people had enough to eat.

He was accompanied by hundreds of people. Riders on horseback went out ahead on the road to let the people know that the Emperor was coming. Next came the many horses carrying the baggage, tended by more riders on horseback. Then came skilled warriors, with their bows and arrows slung over their shoulders, also riding horses. They were followed by more warriors walking just ahead of the emperor. The emperor himself rode in an open carriage drawn by magnificent white horses; a golden parasol protected the emperor from the sun. Behind him marched more warriors carrying long lances that pointed high in the air.

The emperor went from city to city, riding through villages and towns. Everywhere they went, he and his advisors asked questions to learn if the people were living happy and peaceful lives.

When the stopped in one town, the townspeople told the emperor and his advisors about a large family which was known as being the happiest and most peaceful family.

“We must go to visit this family,” said the emperor to his advisors. “We must find out what makes them special.”

The townspeople gave them directions, and soon they arrived. A man named Chang-kung greeted them, bowing low before the emperor, and asking them to partake of what humble food and drink he could offer such distinguished guests.

“My dear Master Chang-kung,” said one of the emperor’s advisors, “what we most desire is not refreshments, but an answer to a question.”

Chang-kung said he would be happy to answer any question they might wish to ask.

“The emperor has heard of your family,” said the advisor, and the emperor nodded in agreement. “The townspeople say that yours is the most peaceful and the happiest family anywhere.”

“There are nine generations of our family living here,” said Chang-kung. “The second cousin of my great-grandmother is the oldest member of our family.” He pointed to an old woman sitting nearby, who was attended by two young men. All three of them were smiling and appeared happy. “And my eldest brother’s great grandchild, born this past winter, is the youngest member of our family.” He pointed to a smiling woman who was carrying a laughing baby. “I cannot say if ours is the happiest and most peaceful family anywhere, but it is true that we live in peace and happiness.”

And it did seem to be the case that everyone they saw appeared to be happy. The children played among themselves, but there were no tears, no arguments, no shouting. The adults worked at various tasks, and again there were no arguments or raised voices. Even the dogs seemed to be kind and peaceful, and they watched as one dog gave a bone to another.

“The emperor would like to ask you this question,” said the advisor: “How it is that so many people live together so peacefully?”

Chang-kung turned to a young man who stood near by, and asked him politely to go and fetch ink, paper, and a brush. The young man returned in an instant with the paper and brush, and a young woman followed him carrying a small table.

Chang-kung began writing rapidly on the paper. The advisors leaned closer to watch him writing. “But you are writing the same word over and over!” said one of the advisors in surprise.

“That is true,” said Chang-kung. He held up the paper so that the emperor could see it.

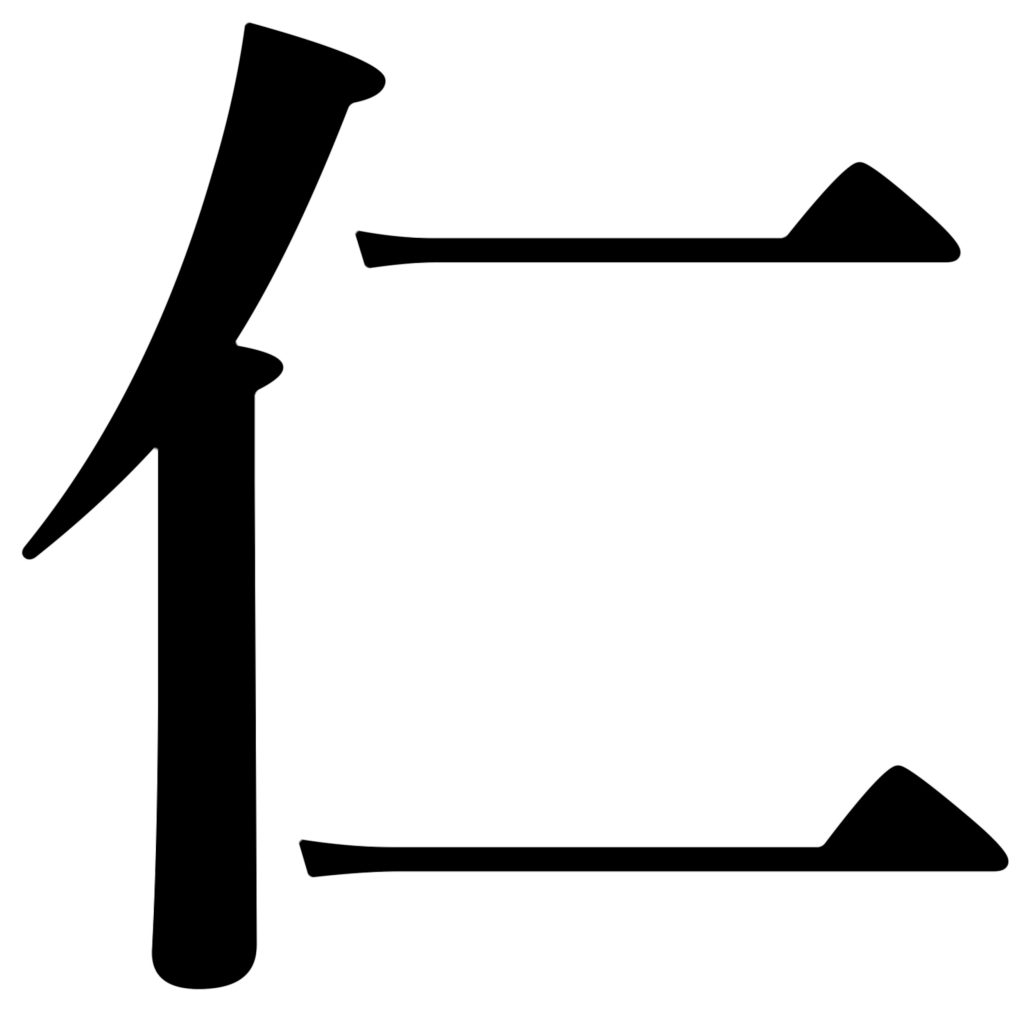

The same character was written over and over—the Chinese word rén — which in English can mean harmony, kindness, or forbearance.

Chang-kung pointed to what he had written. “This is why we live in peace and harmony,” he said. “This is the most important thing.”

The emperor looked at his advisors.

The first advisor said, “It is as Confucius said in the Analects: ‘The person of perfect virtue, wishing to be enlarged, enlarges others.’ This is ren.”

The second advisor said, “Confucius also said: ‘Look not at what is improper; listen not to what is improper; speak not what is improper; make no movement which is improper.’ This is ren.”

The third advisor said, “Confucius also said, ‘Kindness is not far off; the person who seeks for kindness has already found it.’ This is ren.”

“As to that, I cannot say,” said Chang-kung, bowing low. “You are all educated people and I am not. I can only say that in our family we respect the humanity of each other. And we do this by showing kindness.”

Source: See Note to Leader.

Session plan

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story

Read “Chang Kung’s Secret” to the children.

III/ Act out the story

This is a very simple story to act out, and a good way to help the class (children and adults!) to learn how to act out a story.

Ask: “Who are the characters in this story?” In this story, the main characters are Chang Kung, Chang Kung’s large family, Chang Kung’s family’s dogs, the Emperor, and the people in the Emperor’s royal procession. So there is a role for everyone!

Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with you; you will sit facing the stage.

The lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. Actors do not have to repeat dialogue, although some of them will want to do so. The lead teacher may wish to simplify the story on the fly, to make it easier to act out.

It would be great if you took photos of this story with your phone or a digital camera. Print out these photos, and post the best ones on the class bulletin board to remind the children of this story. This will help reinforce the idea that you will be acting out stories during this curriculum.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group. Go over the story to make sure the children understand it. Remind them that Chang Kung had a huge family and yet there were never any quarrels.

If children in your class are studying Chinese, ask if any of them have been exposed to the word “ren.” If so, ask them how that word has been translated in their studies. (N.B.: the word “ren” can be translated by several different English words, such as kindness, forbearance, being humane, etc.; some English translations of this basic story use the word “forbearance” instead of “kindness.”)

Now ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

Ask some questions specific to the story: “If the Emperor came to visit your family, do you think the Emperor would see any quarrels or fighting going on in your family? What kind of quarrels or fighting happens in your family? Do you think kindness might help stop some of the quarrels in your family? What could you do to bring kindness to your family?” Or ask any questions you wish to help the children think about the story.

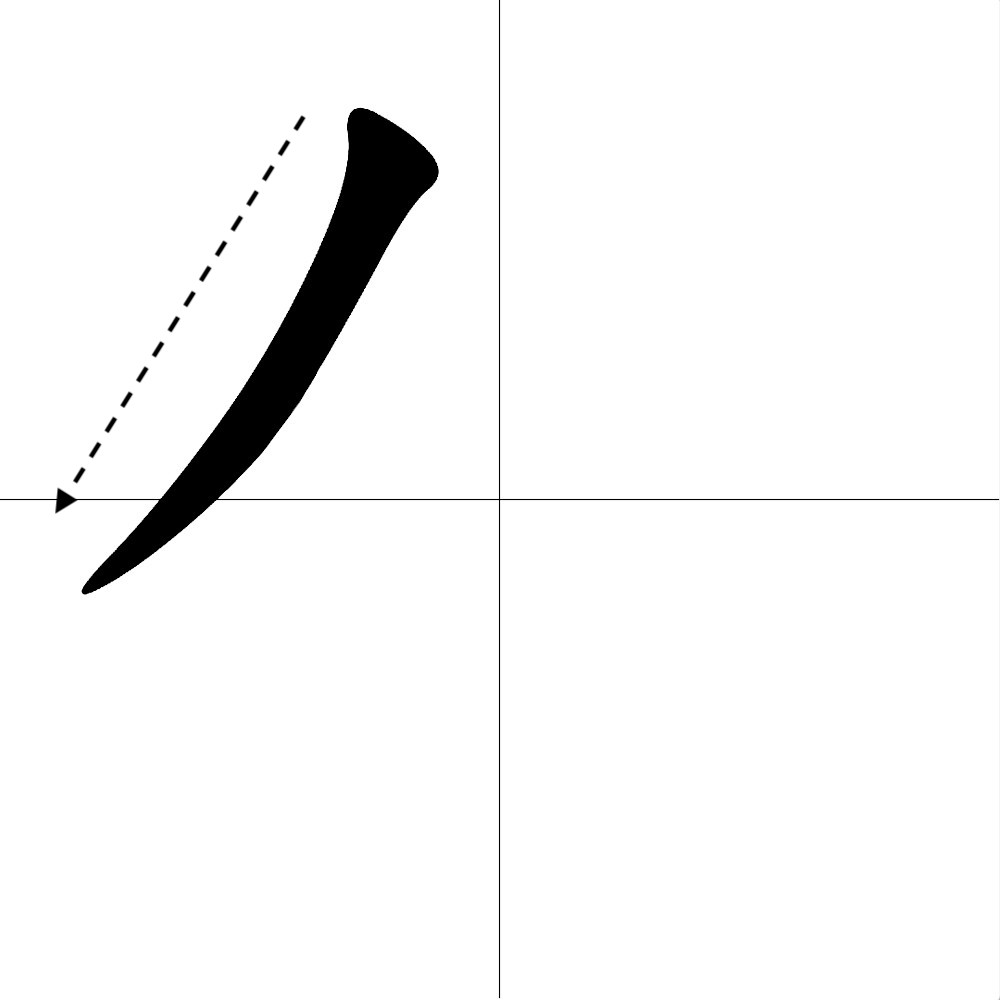

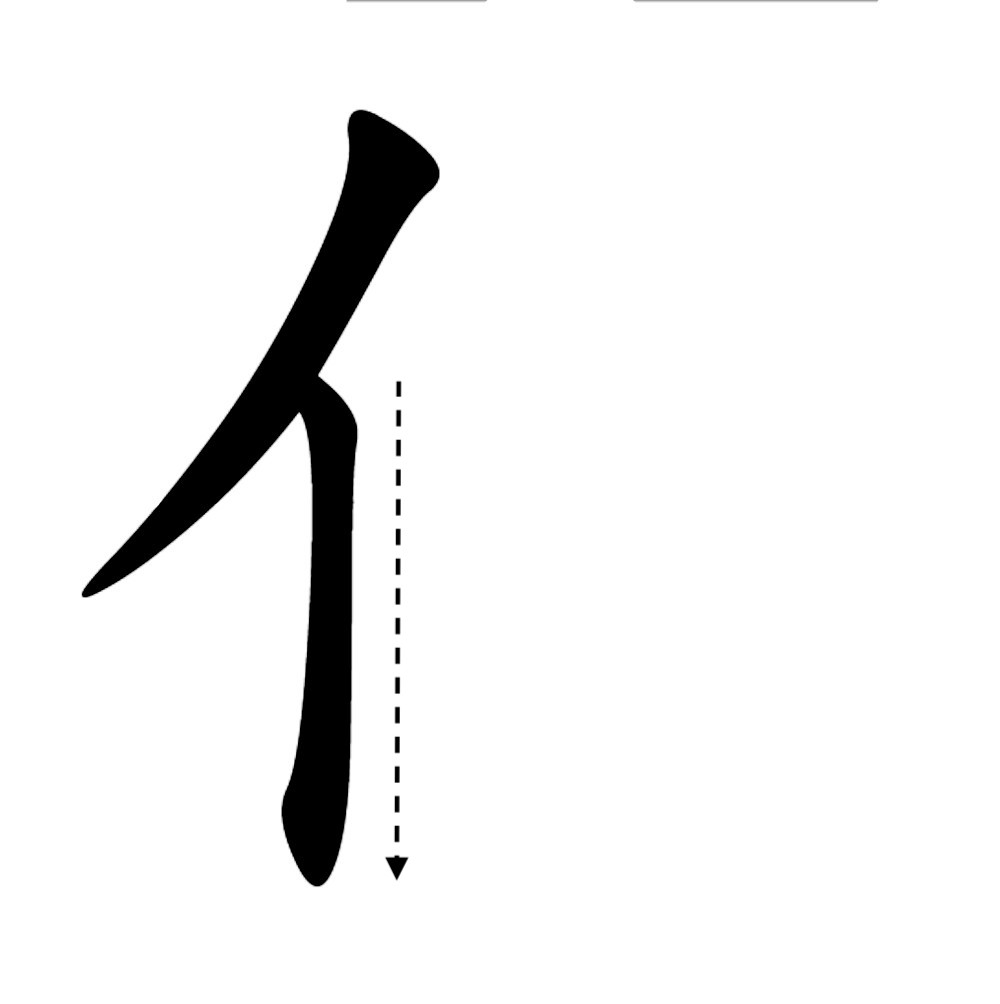

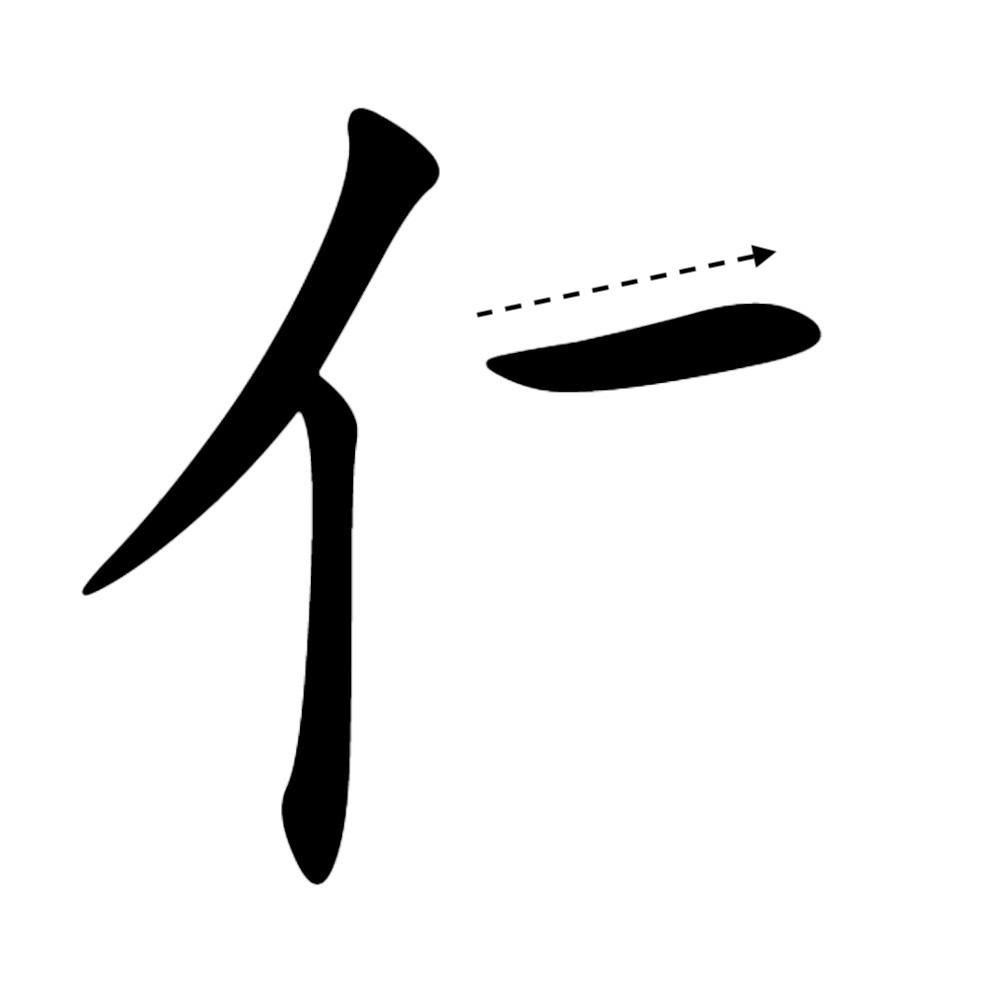

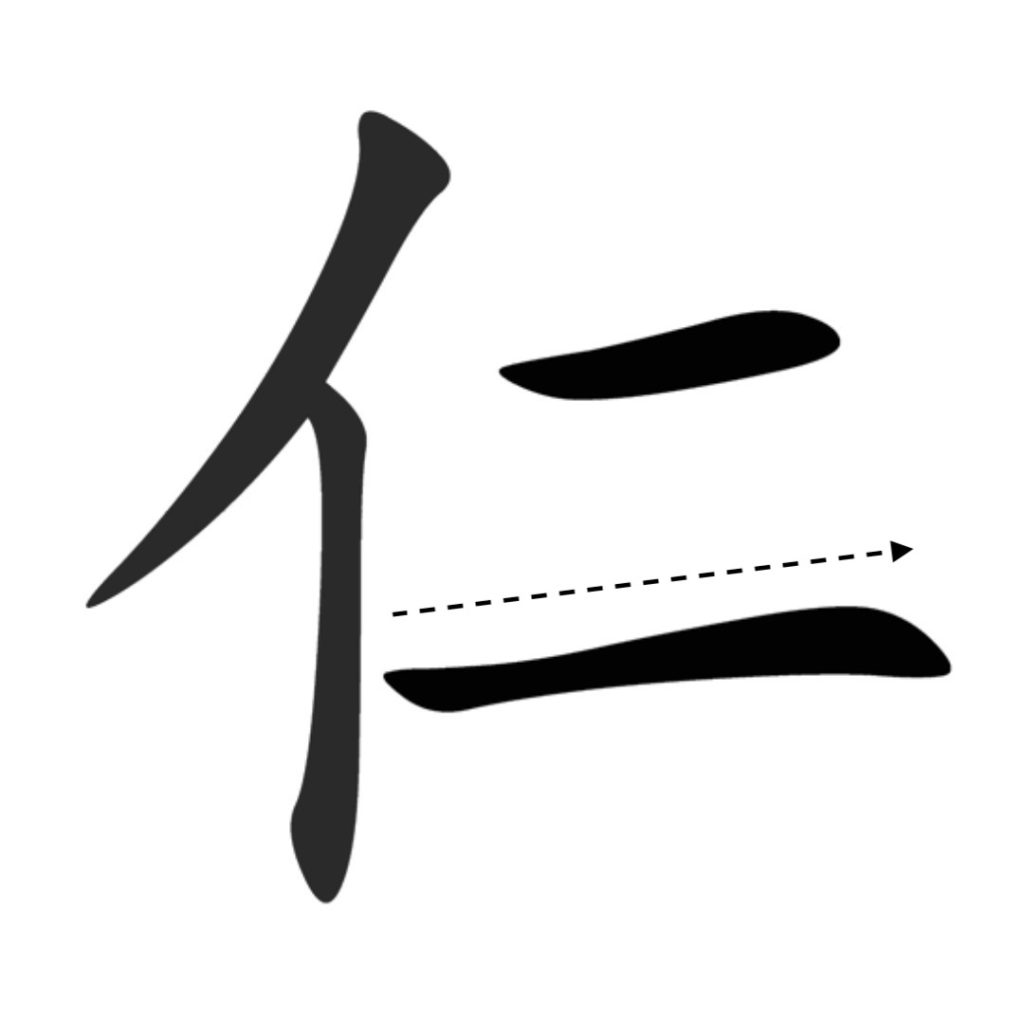

V/ Writing “ren” characters

If you have time, have the children make signs with the “ren” character to hang in their own homes. (As an alternative, a child could write “kindness” in English, and decorate it.) See the drawings below for the correct order and direction in which to draw each of the strokes of the character.

If you have access to someone who knows how to write Chines, and who could show how to write the Chinese characters properly, that would be best.

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about the family of Chang Kung and how they got along well together.” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

Say the closing words together — either these words, or others you choose:

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

Notes to leaders

Source

The basic story comes from a book of maxims attributed to Emperor K’ang-hsi [Kangxi], who ruled China from 1661-1722, an early emperor of the Ch’ing [Qing] dynasty. These maxims appeared in English translation in 1817 as The Sacred Edict, Containing Sixteen Maxims of Emperor Kang-He, Amplified by his Son, the Emperor Yoong-Ching, trans. Rev. William Milne (London: Black, Kingsbury, Parbury, and Allen, 1817), pp. 51-52:

“Formerly, nine generations of Chang-kung-e inhabited the same house; and a Mr. Chin of Keang Chow had seventy persons who all ate together. Those who belong to one family, and are of one surname, should think of their ancestors; rather exceed, than be deficient in respect; rather surpass, than be wanting in kindness. When there is prosperity, rejoice mutually, by an interchange of social affections; when adversity, sympathize mutually, by affording reciprocal aids. In building a family temple to sacrifice to ancestors; in erecting a domestic academy for instructing youth; in purchasing a charity field for the supply of indigent brethren; and in correcting the family calendar, to interweave the names of the more distant relatives — let the same mutual aid be afforded.”

Background

The Sophia Fahs curriculum on which the present curriculum is based had a story titled “The Picture on the Kitchen Wall.” I discuss why that story is problematic in this 2015 blog post. To avoid the problems in the Fahs story, I separated out the story of Chang-Kung from the story of the Kitchen God; that’s the story found in this session.