Beginnings: Myths and stories from world religions

A curriculum for upper elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2014, 2024 Dan Harper.

Back to Table of Contents | On to Session 2

The Moon and the Hare: A story from the San People

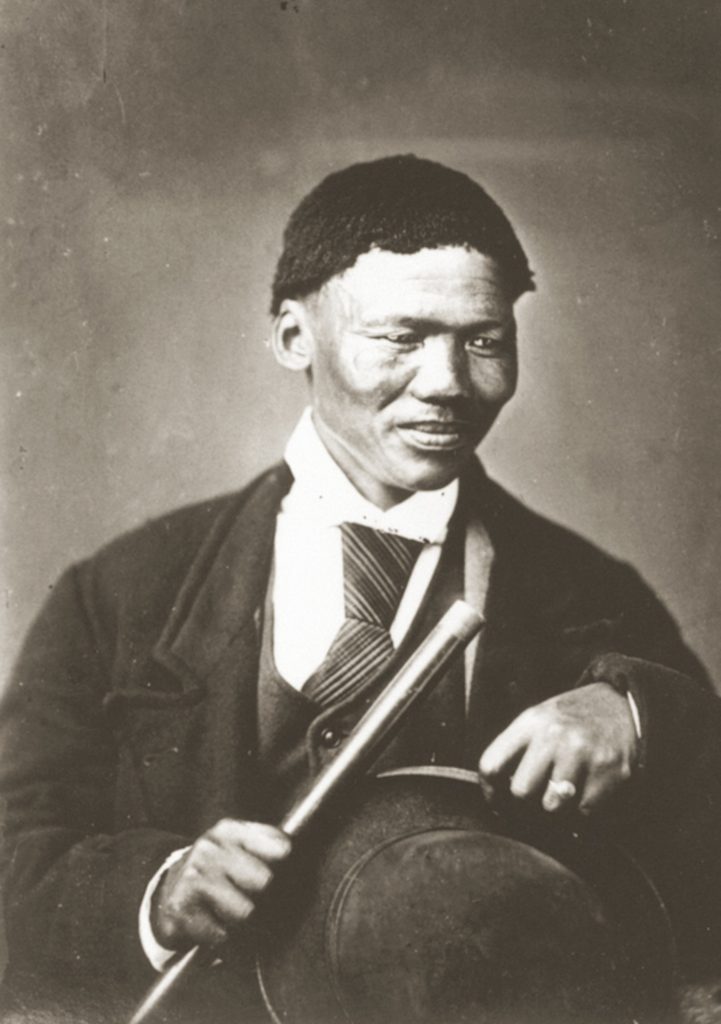

This story was originally told by a man named Dia!kwain, who lived in the southern part of Africa over a hundred years ago, and spoke the |Xam language.

The |Xam language used “click” sounds. Here’s how to pronounce the click sounds that appear in this story:

The symbol | represents a dental click — you make this sound by pressing the tip of your tongue against your upper front teeth, and withdrawing it suddenly.

The symbol ! represents a “cerebral click” — you make this noise by curling up the tip of your tongue against the roof of your mouth, and withdrawing it suddenly.

The symbol || represents a lateral click — you cover the whole roof of your mouth with your tongue, and make the click noise as far back in your mouth as possible. (People who rider horse sometimes use a similar sound to urge a horse forward.)

In addition, the “X” sound is made like the “ch” in the Scottish word “loch.”

The |Xam language is now extinct — that is, there is no one left alive who grew up speaking this language. The people who once spoke |Xam are part of a larger ethnic group commonly referred to as “Bushmen,” although it’s more proper to call them the San people.

This story is one of the San people’s folk tales.

The Origin of Death

When the San people first saw the new moon, they would look towards it, and put their hands over their eyes, and say this:

“!kabbi-a — up yonder in the sky!

Take my face up yonder!

You shall take my face there.

You shall give me your face,

Your face with which, when you have died

You return once again, living.

When you were a new moon,

We did not see you, but now

You come again, lying down.

May I be like you. For you

Always possess joy up in the sky;

When we did not see you,

You always return alive again

And the hare told you this,

That you should do this.

And you did once say

That wee too should return

Alive after we had died.

Having said this prayer, once a man of the San people named Dia!kwain followed the prayer by telling this story:

In the beginning, the hares looked much like a human beings. And when they died, they did not die forever, for after a time they would return to living once again.

There was a young male hare whose mother died. She would not return to life, for she was altogether dead. Seeing this, the hare cried out for his mother.

Public domain photo from NASA.

The Moon heard the hare. “You should leave off crying,” he said to the hare. “Your mother is not altogether dead. She will return to living once again, just as I do. When I am dead, I return, and once I return I am living once again.”

“I am not willing to be silent,” said the hare. “You are wrong. I know that my mother will not become alive again. She is altogether dead.”

The Moon became angry that this young hare should speak this way, and not agree with what the Moon said. So the Moon hit the hare in the mouth, splitting the hare’s lip. “The hare’s mouth shall always be like this,” said the Moon. And the Moon gave the hare the form that all hares have today, with a lip that is in two parts, and longs legs for running.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International by Giles Laurent. Photo cropped.

“The hare shall always bear this scar on his face,” said the Moon. “And the dogs shall always chase him, and he shall have to spring away, doubling back and forth as he tries to run away. If the dogs catch him, they will bit him and tear him to pieces, and he will altogether die, and never return to living once again.”

“And they who are human beings,” said the Moon, “when they die, they too shall altogether die, and never return to living once again. For the hare was not willing to agree with me when I told him that he should not cry for his mother. The hare was not willing to agree with me when I told him that his mother was not altogether dead, but would return to living once again.

“I told the hare,” the Moon went on, “that all people should be like me, and do that which I do. When I am dead, I return, and once I return I am living once again. But the hare contradicted me, when I told him that.”

And the Moon spoke further, saying: “All you who are people, when you die you shall altogether vanish away. Before this, I said that when people died, you could return to living once again — just the way that when I die, I again return living. I had meant for all you who are people, that you should resemble me and do the things I do. I had thought that I would give you joy. But the hare, when I tried to tell him about this — when I tried to tell him that his mother had not really died, but that she only slept — the hare was the one who said that his mother did not sleep, that she had altogether died. This is what I became angry about, for I thought the hare would say, ‘Yes, my mother is just asleep’.”

Because of the hare, the Moon changed the way death worked for all of us. And this is the story that tells why when we die, we die altogether, never to return.

The storyteller Dia!kwain went on to add:

This is the story of the hare that San mothers told to their children: the hare had once been like a human being, but when he talked the way he did to the Moon, the Moon cursed him, and turned him altogether into a hare. And the San mothers told their children that to this day, hares have a bit of human flesh left in them. For this reason, the San mothers would say to their children, when they killed and ate a hare, there was one small piece of meat, called the ||katten-ttu, which they should not eat.

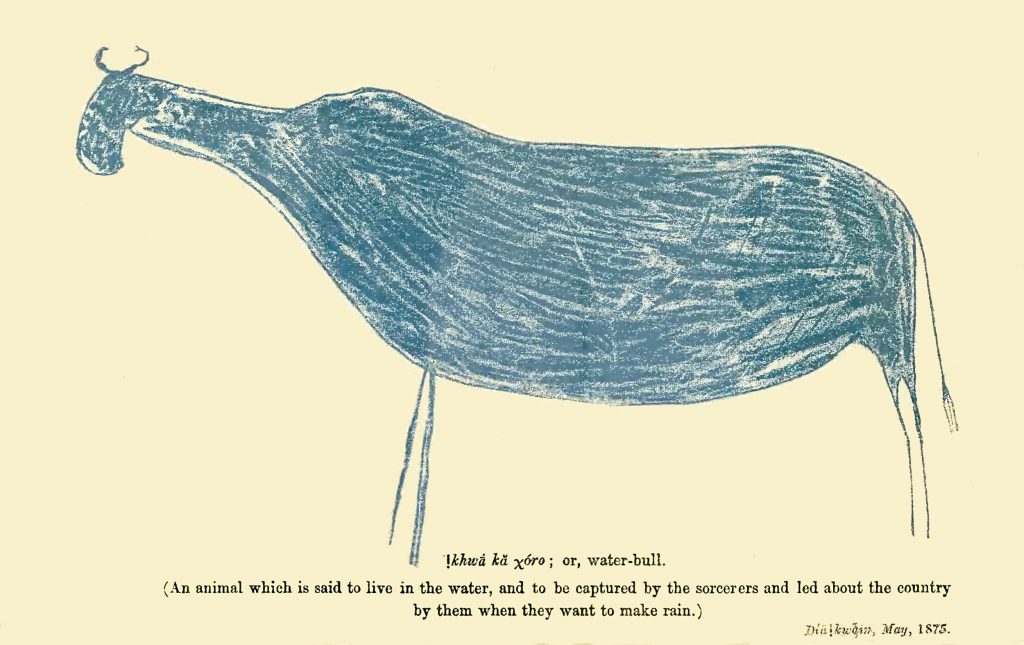

Public domain image (from Specimens of Bushman Folklore, 1911).

Source and Notes:

This story comes from “The Origin Of Death; Preceded By A Prayer Addressed To The Young Moon,” Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek, Lucy C. Lloyd, Specimens of Bushman Folklore (London: George Allen & Co., 1911). I stuck to this original text, a translation of the original |Xam language, as much as possible, but rearranged the story and removed some redundancies to conform to narrative norms of written English.

The story was dictated to Bleek and Lloyd in 1875 by Dia!kwain: “Dia!kwain gives fifteen pieces, which are in the Katkop dialect, which Dr. Bleek found to vary slightly from that spoken by ||kabbo and |a!kungta. He came from the Katkop Mountains, north of Calvinia (about 200 miles to the west of the homes of |a!kungta and ||kabbo). He was at Mowbray from before Christmas, 1873, to March 18th, 1874, returning on June 13th, 1874, and remaining until March 7th, 1875” (from the Preface).

The descriptions of how to pronounce the click sounds is also taken from this book (see pp. vi. ff.).

Session One: The Moon and the Hare

Materials

Paper and drawing materials (crayons, etc.)

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story

Read “The Moon and the Hare” to the children.

III/ Act out “The Moon and the Hare.”

One of the principal ways we will help children internalize the story is to have them act it out. Some of the children may be familiar with how to act out a story, but others won’t be. This is a very simple story to act out, and a good way to help the class (children and adults!) to learn how to act out a story.

Ask: “Who are the characters in this story?” (In this story, the Moon and the Hare are both characters; you could also include the dead mother hare as well.)

Determine where the stage area will be. Children who are not actors may sit facing the stage area.

The lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. Actors do not have to repeat dialogue, although some of them will want to do so. The lead teacher may wish to simplify the story on the fly, to make it easier to act out.

Since this is such a simple story, you may want to act it out twice, with different sets of actors each time.

Be sure to bring a digital camera (e.g., your cell phone), and take photos of the children acting out this story. Print out these photos, and post the best ones on the class bulletin board to remind the children of this story.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group.

In case someone hasn’t yet understood, explain that the Moon goes through phases, and every twenty-eight days it is not visible in the night time sky. We call this the “new moon,” while the San thought about it as though the moon dies and then comes back to life.

Ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

Ask some questions specific to the story: “Why did the Moon get angry at the Hare? Do you think it was fair that the Moon got angry at the Hare? Do you think it was fair that just because the Hare misunderstood, now all creatures were going to have to die?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

You can continue the conversation in any way you wish.

V/ Optional: tell another San story

The Leader Resource section has another story told by Dia!kwain. This second story tells what happens after death.

If you wish, you can read that story to the children, then talk about it.

VI/ Illustrate the story

If you have time, ask the children to draw pictures of the Moon and the Hare, so you can put some pictures up on the bulletin board in your classroom.

Here are some ideas for pictures the children might want to draw:

- The Hare before the Moon split his lip (when he looked more like a human being)

- The Hare after the Moon split his lip (when he looked like he does today)

- The Moon as a full moon

In the “Notes to Leaders” below, there is another brief story by Dia!kwain telling about the moon and death. In this story, Dia!kwain describes the Moon as being like a boat (sometimes when the moon is new, it does look like a boat). When the Moon is like this, it may be carrying people who have died. This provides a couple more ideas of pictures the children might draw:

- The Moon when it is new

- The Moon carrying people who have died

Public domain image (from Specimens of Bushman Folklore, 1911).

VII/ Building community through play

If you don’t want to do the art activity, you can set aside more time for play.

Game ideas to build community through play: “Duck, Duck, Goose” (yes, this age group finds this game amusing) or other games.

IX/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children sit or stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

After you’ve reviewed what the children learned for a couple of minutes, say together some closing words, either the ones below or something you choose. Tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

LEADER RESOURCES

1. Dia!kwain

The story of the |Xam people is tragic. During Dia!kwain’s lifetime, White settlers began moving into the lands his |Xam people lived in. There were many violent conflicts between the Whites and the |Xam. Dia!kwain was imprisoned for killing a Boer farmer who had threatened to kill Dia!kwain and his entire family. While he was imprisoned, Dia!kwain met Dr. Wilhelm H. I. Bleek and Lucy Lloyd, who wanted to study |Xam language. Bleek and Lloyd recorded many of Dia!kwain’s retelling of traditional stories, as well as a poem he wrote himself. When Dia!kwain was released from prison in 1876, he was soon murdered by friends of the Boer farmer. More about Dia!kwain. — His poem “The Broken String” in English translation.

2. Another story: What happens after death?

What happens after humans die? The following story was told by Dia!kwain, and comes from Bleek’s collection of |Xam folklore. It has been lightly edited to make it more readable.

The relation of the wind, moon, and cloud to human beings after death

…When we die, our (own) wind blows; for we, who are human beings, we possess wind. And we make clouds, when we die. Therefore, when we die, the wind makes dust, because it intends to blow and take away our footprints, which we left when we were well and alive; for our footprints, which the wind intends to blow away, would otherwise still lie plainly visible. If our footprints remained, it would seem as if we still lived. Therefore, the wind will blow, taking away our footprints….

When the moon was lying down came, when the moon stood hollow, Mother spoke and said: “The moon is carrying people who are dead…. This is why it lies hollow…. You may expect to hear something, when the moon lies in this manner. A person is the one who has died, he whom the moon carries. Therefore, expect to hear something has happened, when the moon is like this.”

And when we die, the hair of our head will resemble clouds, when we in this manner make clouds. These things are those which resemble clouds; and we think that they are clouds. We, who do not know, we are those who think in this manner, that they are clouds. We, who know, when we see that they are like this, we know that they are a person’s clouds; that they are the hair of a person’s head. We, who know, we are those who think thus, while we feel that we seeing recognize the clouds, how the clouds form themselves like this.