Beginnings: Myths and stories from world religions

A curriculum for upper elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

Updated 2024

Back to Table of Contents | On to Session 7

Pangu: A Story from China

The Chinese religions that are best known in the West are Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism. But Chinese popular religion, while not as well known to Westerners, is just as important, or even more important. The story of Pangu comes from Chinese popular religion.

In several regions of China, people built temples to Pangu (PAN koo) in ancient times. In Henan Province, one temple to Pangu was built in Pangu Mountain, which is said to be the place where Pangu himself once lived. Even today, people still worship Pangu there, and there is a big fair for Pangu at the temple which begins on March 3 (of the lunar calendar) and lasts for about a week. As many as 100,00 people, many who come from far away, may attend this festival for Pangu. There are still active temples to Pangu throughout China.

No one knows where the myth of Pangu originated. It was not written down until about the third century of the common era. Some scholars believe that the myth of Pangu comes from the Han Chinese people, while others think it came from Chinese people who are not part of the Han ethnic group. (A few scholars even believe that the myth of Pangu came from India.) Wherever the myth comes from, the story of Pangu includes two very important features of Chinese mythology: that the world came from the body of a deity that was dying; and that the world started with chaos in the shape of an egg.

Pangu and the beginning of the universe

At the beginning, there was little difference between heaven and earth. All was chaos, and heaven and earth had no distinct forms, like the inside of a chicken’s egg. Within this chaos, the god Pangu was born inside the egg.

Pangu grew and grew inside the egg. After 18,000 years, the egg somehow opened up. Some say that Pangu stretched himself inside the egg, and shattered the egg’s shell into pieces.

Once the egg had shattered open, the lightest part of it, the part that was like the white of a chicken’s egg, rose upwards, and became the heavens. The heavier part of the egg, like the yolk of a chicken’s egg, sank downwards and became the earth. Pangu took a hammer and an adze, and cut the connections between earth and the heavens. Then to keep earth and the heavens from merging together once again, Pangu stood between them, serving as the pillar that kept them apart.

Pangu lived within earth and the heavens, standing between them. And one day he began to transform. He became more sacred than the earth, and he became more divine than the heavens. The heavens began to rise, going up one zhang, or about ten feet, each day. The earth began to grow thicker, thickening by one zhang each day. And as the heavens rose, so too Pangu grew; he grew one zhang taller each day. And this continued for 18,000 years: each day, the earth grew thicker, and the heavens rose higher, and Pangu grew taller.

At the end of 18,000 years, the heavens had grown very high, the earth had grown very thick, and Pangu had grown into a giant. He was now 90,000 li (or 87,000 miles) tall, the distance between earth and the heavens. Finally, all had become stable. The heavens had stopped rising. The earth had stopped growing thicker.

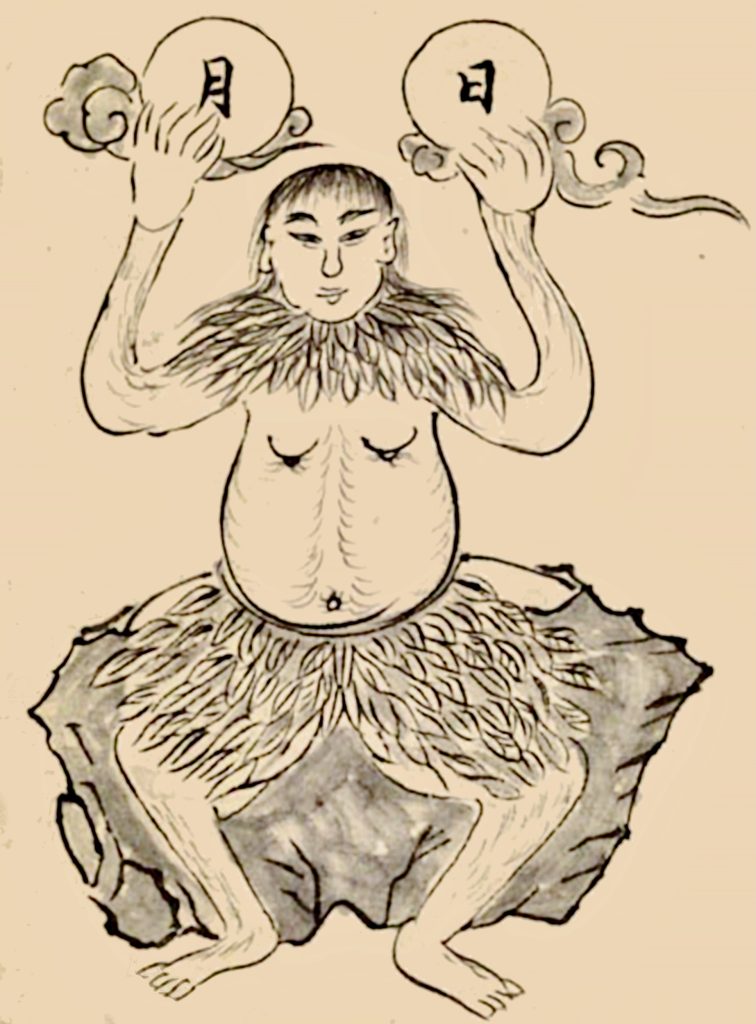

Not everyone agrees what Pangu looked like. Some say he had a dragons’ head and the body of a serpent. But most say he looked like human beings, except that he was a giant, and he had a horn on his head.

After uncounted years, Pangu felt that he was dying. As he was dying, his body began to transform itself.

His left eye became the sun, his right eye became the moon, and his hair and beard became the sky and the stars. His breath became the winds and clouds, and his voice became the thunder. His arms and legs became the four extremes or borderlines of the earth, and his head and torso became the Five Mountains. His blood became the rivers, his teeth and bones became the rocks and minerals, and his flesh became the fields and the soil. His skin became plants, and his sweat became the rain and the dew.

So it was that when he died, the body of Pangu became the whole universe and everything in it.

Sources and notes:

The first part of the story is from the Sanwu Liji, or San Wu Li Ji; and the second part of the story is from the Wuyun Linianji, or Wu Yun Li Nian Ji.

Translation and retelling from Handbook of Chinese Mythology, Lihui Yang and Deming An (Oxford University, 2005), pp. 64-66, 170-176; with reference to Classical Chinese Myths, Jan Walls and Yvonne Walls (Hong Kong: Joint Publishing, 1984); and Chinese Myths and Legends, Lianshan Chen (Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp. 6-7.

See also Asian Mythologies, ed. Yves Bonnefoy (University of Chicago, 1993), pp. 234 ff.

Session Six: Pangu

Materials

Optional: print the Pangu coloring page above

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

Review last week: If you took photos of last week’s skit, show them to the children, and have them help you post them on the class bulletin board (remember to leave lots of room on the class bulletin board for pictures from future classes).

II/ Read the story

Read “Pangu and the beginning of the universe” (see above).

III/ Creative movement exercise

There’s really only one character in the story, so instead of making this into a skit (which is difficult or impossible), have each child act this out as a kind of creative movement exercise: breaking out of the egg, growing taller each year, etc.

Ask: “What happened first in the story? Then what happened? then what happened?” — and as they remember one thing, work with them to act it out. When one child comes up with a particularly good way of expressing a part of the story, point it out to the other children (so they can copy it, if they want to).

Some people find it is helpful to lead creative movement exercises to a slow drumbeat. You could bring a drum, or simply beat a slow rhythm on a tabletop or chair. Sometimes it helps to have your assistant teacher beat out the slow rhythm while you read the story.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story for you?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

Ask some more specific questions: “What did you think about the idea of the universe coming out of an egg? [Note the vague similarity between this idea, and Big Bang theory, where everything comes from some initial primordial mass.] But where do you think that egg came from? [Note that this is an interesting question for the Big Bang theory: where did the primordial mass come from, and why did it explode?] Why did Pangu start growing? What do you think about the idea of Pangu’s dead body forming the earth that we live on?”

V/ Illustrations of Pangu

Pangu has been imagined in many different forms by ancient and contemporary artists. Searching the Web will turn up lots of contemporary depictions of Pangu, including comic books characters.

If you want to, you could assign a different stage of the story to each child: Pangu stretching himself inside the egg, the egg shattering, Pangu cutting the connections between heaven and earth, Pangu growing, Pangu dying, the parts of Pangu forming the earth, etc.

VI/ Building community through play

If you don’t want to do the art activity, you can set aside more time for play.

Game ideas to build community through play: “Duck, Duck, Goose” (yes, this age group finds this game amusing) or other games.

VI/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children sit or stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

After you’ve reviewed what the children learned for a couple of minutes, say together some closing words, either the ones below or something you choose. Tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.