From Long Ago

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper, v. 2.0

Copyright (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

The Two Friends

Once there were two friends, one of whom was a follower of Buddha, and the other of whom was an old person who lived nearby. The follower of Buddha used to go every day to the house of the elder, where they would eat together. Then the follower of Buddha returned to the community of people that lived with Buddha.

Some of Buddha’s other followers were talking about these two friends, and Buddha overheard them. “Ah yes,” said the Buddha. “Those two were great friends in a past life.” (For all of Buddha’s followers believed that they had had many past lives.) And then the Buddha told this story of the past:

Once upon a time a Dog used to go into the stable where the king’s Elephant lived. At first the Dog went there to get the food that was left after the Elephant had finished eating.

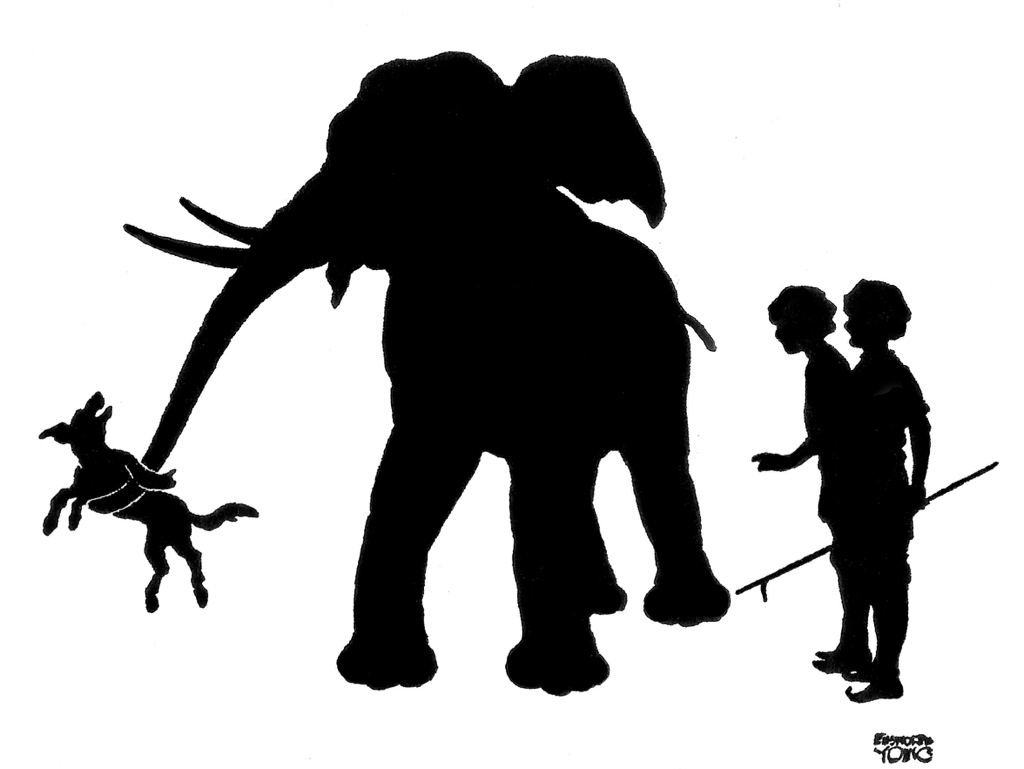

Day after day the Dog went to the stable, waiting around for bits to eat. But by and by the Elephant and the Dog came to be great friends. Then the Elephant began to share his food with the Dog, and they ate together. When the Elephant slept, his friend the Dog slept beside him. When the Elephant felt like playing, he would catch the Dog in his trunk and swing him to and fro.

Public domain illustration by Ellsworth Young, 1922.

Neither the Dog nor the Elephant was quite happy unless the other was nearby.

One day a farmer saw the Dog and said to the Elephant-keeper: “I will buy that Dog. He looks good-tempered, and I see that he is smart. How much do you want for the Dog?”

The Elephant-keeper did not care for the Dog, and he did want some money just then. So he asked a fair price, and the farmer paid it and took the Dog away to the country.

The king’s Elephant missed the Dog and did not care to eat when his friend was not there to share the food. When the time came for the Elephant to bathe, he would not bathe. The next day again the Elephant would not eat, and he would not bathe. The third day, when the Elephant would neither eat nor bathe, the king was told about it.

Public domain illustration by Ellsworth Young, 1922.

The king sent for his wisest advisor, saying, “Go to the stable and find out why the Elephant is acting in this way.”

The wise advisor went to the stable and looked the Elephant all over. Then he said to the Elephant-keeper: “There seems to be nothing the matter with this Elephant’s body, but why does he look so sad? Has he lost a playmate?”

“Yes,” said the keeper, “there was a Dog who ate and slept and played with the Elephant. The Dog went away three days ago.”

“Do you know where the Dog is now?” asked the wise advisor.

“No, I do not,” said the keeper.

Then the wise advisor went back to the king and said, “The Elephant is not sick, but he is lonely without his friend, the Dog.”

“Where is the Dog?” asked the king.

“A farmer took him away, so the Elephant-keeper says,” said the wise advisor. “No one knows where the farmer lives.”

“Very well,” said the king. “I will send word all over the country, asking the man who bought this Dog to turn him loose. I will give him back as much as he paid for the Dog.”

When the farmer who had bought the Dog heard this, he turned him loose. The Dog ran back as fast as ever he could go to the Elephant’s stable. The Elephant was so glad to see the Dog that he picked him up with his trunk and put him on his head.

Public domain illustration by Ellsworth Young, 1922.

Then he put him down again. When the Elephant-keeper brought food, the Elephant watched the Dog as he ate, and then took his own food.

All the rest of their lives the Elephant and the Dog lived together.

Buddha’s followers knew that when he told one of these stories, he was also telling about one of his past lives. And the Buddha said, “My follower was the dog of those days, the aged Elder was the elephant, and I myself the wise advisor.”

Source: Adapted from “The Elephant and the Dog,” from More Jataka Tales by Ellen C. Babbitt (New York: Appleton-Century, 1922). Illustrations by Ellsworth Young from this same book. The original Jataka tale, no. 27, Abhinha-Jataka, may be found in English translation in The Jataka, or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births, Volume I, trans. Robert Chalmers, ed. E. B. Cowell (Oxford, 1895), pp. 69-70 (see below).

Session eight: The Two Friends

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story

Read the story to the children.

III/ Act out the story

As usual, begin by asking: “Who are the characters in this story?” The main characters in this story are of course the Elephant and the Dog. Other important characters include the King’s chief adviser (in the original, this chief adviser was supposed to be an earlier incarnation of Buddha himself); the Elephant-keeper; the farmer who took the dog away.

Determine where the stage area will be, and the lead teachers sits facing the stage. As usual, the lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. Depending on the size of the class, some children make take on more than one role.

If you think about it, take some photos of the children acting out the story, print them out later, and post them on the bulletin board in your classroom.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group. Go over the story to make sure the children understand it.

Now ask some general questions: “What did you like about the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

Ask some questions specific to the story: “What do you think about the elephant keeper selling the elephant?” “Do you think animals as different as elephants and dogs could actually become best friends? Why or why not?” “Did you ever have a best friend move away so you hardly saw them again? What did it feel like?” — or other open-ended questions.

Since you’ve been discussing stories week after week, by now the children should be pretty good at it. The children will be interested in thinking about whether either of these stories is really true or not, and that question should lead to some very interesting discussions. Ask them: do you think this story could have been really true? (This story is not likely to be historically true; nevertheless, the children may find that it has some elements of truth to it.)

V/ End of course conversation

This is the last session in this curriculum. At this point, it would be good to do some quick review. Ask the children to help you name all the stories they have heard in the past eight weeks; write them down where everyone can see them. If you’ve posted photos, drawings, or other materials from the course on you classroom bulletin board, look at those materials to help you remember.

Now go over the stories, and see who likes which story best. (You can encourage the children who were present for a given story to explain it to the children who missed that session.) Why did you like your favorite story?

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? Etc.” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

Say the closing words together — either these words, or others you choose:

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them today, and that you have enjoyed teaching this course to them!

Note to leaders

For your reference, here’s an English translation of the original Jataka tale, from The Jataka, or Stories of the Buddha’s Former Births, Volume I, trans. Robert Chalmers, ed. E. B. Cowell (Oxford, 1895), pp. 69-70:

No. 27, ABHIṆHA-JĀTAKA.

“No morsel can he eat.” — This story was told by the Master while at Jetavana, about a lay-disciple and an aged Elder.

Tradition says that there were in Sāvatthi two friends, of whom one joined the Brotherhood but used to go every day to the other’s house, where his friend used to give him an alms of food and make a meal himself, and then accompany him back to the Monastery, where he sat talking all the livelong day till the sun went down, when he went back to town. And his friend the Brother used to escort him on his homeward way, going as far as the city-gates before turning back.

The intimacy of these two became known among the Brethren, who were sitting one day in the Hall of Truth, talking about the intimacy which existed between the pair, when the Master, entering the Hall, asked what was the subject of their talk; and the Brethren told him.

“Not only now, Brethren, are these two intimate with one another,” said the Master; “they were intimate in bygone days as well.” And, so saying, he told this story of the past.

Once on a time when Brahmadatta was reigning in Benares, the Bodhisatta became his minister. In those days there was a dog which used to go to the stall of the elephant of state, and eat the gobbets of rice which fell where the elephant fed. Haunting the place for the food’s sake, the dog grew very friendly with the elephant, and at last would never eat except with him. And neither could get on without the other. The dog used to disport himself by swinging backwards and forwards on the elephant’s trunk. Now one day a villager bought the dog of the mahout and took the dog home with him. Thenceforward the elephant, missing the dog, refused either to eat or drink or take his bath; and the king was told of it. His majesty despatched the Bodhisatta to find out why the elephant behaved like this. Proceeding to the elephant-house, the Bodhisatta, seeing how sad the elephant was, said to himself, “He has got no bodily ailment; he must have formed an ardent friendship, and is sorrowing at the loss of his friend.” So he asked whether the elephant had become friends with anyone.

“Yes, my lord,” was the answer; “there’s a very warm friendship between him and a dog.” “Where is that dog now?” “A man took it off.” “Do you happen to know where that man lives?” “No, my lord.” The Bodhisatta went to the king and said, “There is nothing the matter with the elephant, sire; but he was very friendly with a dog, and it is missing his friend which has made him refuse to eat, I imagine.” And so saying, he repeated this stanza:

No morsel can he eat, no rice or grass;

And in the bath he takes no pleasure now.

Methinks, the dog had so familiar grown,

That elephant and dog were closest friends.

“Well,” said the king on hearing this; “what is to be done now, sage?” “Let proclamation be made by beat of drum, your majesty, to the effect that a man is reported to have carried off a dog of which the elephant of state was fond, and that the man in whose house that dog shall be found, shall pay such and such a penalty.” The king acted on this advice; and the man, when he came to hear of it, promptly let the dog loose. Away ran the dog at once, and made his way to the elephant. The elephant took the dog up in his trunk, and placed it on his head, and wept and cried, and, again setting the dog on the ground, saw the dog eat first and then took his own food.

“Even the minds of animals are known to him,” said the king, and he loaded the Bodhisatta with honors.

Thus the Master ended his lesson to show that the two were intimate in bygone days as well as at that date. This done, he unfolded the Four Truths. (This unfolding of the Four Truths forms part of all the other Jātakas; but we shall only mention it where it is expressly mentioned that it was blessed unto fruit.) Then he showed the connexion, and identified the Birth by saying, “The lay-disciple was the dog of those days, the aged Elder was the elephant, and I myself the wise minister.”