Coming of Age program for the UU Church of Palo Alto

Written and compiled by Dan Harper, v. 1.5

Copyright (c) 2014-2022 Dan Harper

Revised April, 2022

Substantial revision, April, 2022: The session plans have been updated as taught in the 2020-2021 Coming of Age class. “God-talk checklist” session has been removed from the curriculum, although the session plan appears at the bottom of this page for those who would like to continue using it. The “What Is Religion?” session has been moved earlier in the class. A new session, “Football Is Religion (Re-defining Religion),” has been added to Unit 2. The purpose of these revisions is that we have increasingly found that the most interesting statements of religious identity tend to be the ones that focus on social justice, ethics, dealing with life’s challenges, etc. This is also appears to be the trend in wider Unitarian Universalism — as a religious movement, we seem less interested in traditional questions of belief, and more interested in ethical issues like racism, sexism, anti-LGBTQ+ bias, etc.; as well as personal questions like “How do I live a good life?”

Coming of Age program description

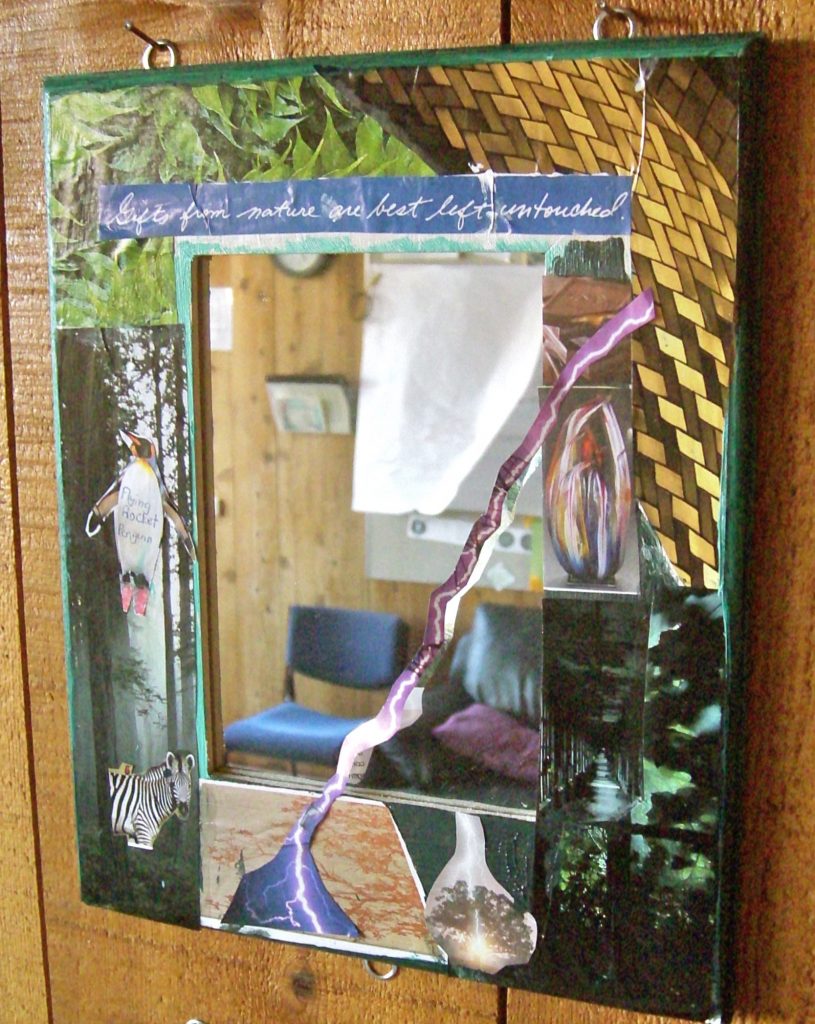

This is a description of the 9-month Coming of Age program, for youth in grades 8-9, as offered at the UU Church of Palo Alto (UUCPA). Primary developer of this curriculum is Dan Harper. Activities were contributed by Lynn Grant (mirrors, self-portrait sculptures); other leaders of the Coming of Age program contributed input and ideas, including Emily Drew-Moyer, Laura Coleman, Mike Abraham, Carol Steinfeld, Edie Keating, Aarav Billore, and others.

Table of Contents

Goals and Objectives

Overview of the Program

About Mentors

A/ Family Meeting

B/ Meetings with Mentors

C/ Social Justice Project

D/ Life-sized Plywood Self Portraits

Unit 1: The Big Religious Questions

Session One: The Big Questions

Session Two: “Who Are You?” — The Mirror Project

Session Three: Mirrors Completed

Unit 2: Religion and Existentialism

Session Four: What Is Religion?

Session Five: Football Is Religion (Re-defining Religion)

Session Six: Existentialism

Unit 3: Religion in Arts and Literature

Session Seven: Unitarian Universalist Poems

Session Eight: Intro to Western Religious Practice

Session Nine: Field Trip To See Asian Art

Unit 4: Writing Statements of Religious Identity, Planning Worship

Session Ten: How To Write Statements of Religious Identity

Session Eleven: Practical Religion

Session Twelve: Time To Work on Statements of Religious Identity

Session Thirteen: Attend the Worship Service

Session Fourteen: Planning the Service

Session Fifteen: Rehearsal

Final Session: Coming of Age Service and Lunch

GOALS AND OBJECTIVES

The goal of our Coming of Age program is to help young people sort out their ethical and religious identity (recognizing that some young people do not feel religious at all), so that they may make rational decisions about the kind of person they want to become. We have three objectives that help us reach this broad goal:

- 1. We want participants to have fun, and to bond with a community of young people who share similar moral and spiritual values.

- 2. We want participants to articulate their own ethical and religious identity, to gain a deeper sense of identity and to present that identity through the arts, spoken word, etc.

- 3. We want participants to engage in direct experience, including social justice projects and the arts, so they can experience living out their religious and ethical values in the world.

We will help young people meet these three objectives through four types of fun activities:

- Participants will meet fourteen times as a group to get to know each other, have fun, and reflect on religion and ethics. Meeting times vary from year to year.

- Participants will meet with an adult mentor of their choice, responsible adults from the congregation who can help them reflect on their identities. We will help young people find appropriate adults from whom they can choose a mentor who will be a good match. Participants meet with mentors once a month (6 times total) from approx. November through April.

- Participants will write a statement of their religious identity (formerly known as a “credo statement”), setting forth their ethical and religious identity as it stands now. These statements are usually about 500-700 words long, and mentors help youth to write their statements of religious identity.

- Participants will lead the Sunday morning service on a Sunday in May, usually the third Sunday (at both services). They will present their statements of religious identity during this service. This will be followed by a closing celebration.

Youth have reported that the Coming of Age program is both fun and meaningful. The program will help them grow in self-knowledge, it will allow them to spend time with youth and adults who share similar values, and it provides additional strong adult role models at a time in life when that’s what many young people are looking for.

OVERVIEW OF THE PROGRAM

Class sessions are a key part of the program. Class sessions balance fun activities and serious activities, hands-on activities and discussions. Class sessions prompt youth to think about their religious identity, write their statements of religious identity, and then prepare for the final Coming of Age service.

Mentors are also a key part of the program. Separate from the class meetings, participants arrange to meet on their own with their mentors five times between January and May (i.e., once a month). Mentor meetings are an excellent time for youth to talk about their their statements of religious identity.

ABOUT MENTORS

In the Coming of Age program, every youth participant is assigned a mentor to help them write their statement of religious identity.

Mentors and youth should plan to meet once a month, for about an hour each month. Some mentors and youth chose to do some kind of getting-to-know you activity like visiting a museum together (just make sure the mentor does not have to be alone one-on-one in a car with the youth). Other teams dive right in to talking about the young person’s religious identity.

The sole goal of the mentor is to help the youth write their statement of religious identity. Mentors can help the young person by acting as a sounding board, a coach, and a cheerleader.

Mentors are also invited to attend Coming of Age classes. While this is optional for mentors, note that there are a couple of classes where they will be specifically invited. Mentors are particularly helpful during the class sessions devoted to writing statements of religious identity. Note that visiting some classes can count as one of the monthly meetings with the youth.

Coming of Age Session Plans

All group meetings take place at the regular meeting time, except where noted.

A/ FAMILY MEETING

One session at the beginning of the school year

Youth and parents meet with the religious educator and Coming of Age teachers to go over the calendar for Coming of Age, and ask any questions about the program.

B/ MEETINGS WITH MENTORS

Six meetings, November through April, self-scheduled

In addition to the group meetings, participants will arrange to meet on their own with their mentors at least six times from January through May. Mentor meetings are an excellent time for youth to work on their statements of religious identity. It is possible for youth to complete their statements of religious identity during mentor meetings and class time, without any additional time commitment. (Note that Coming of Age graduates tell us that the mentor meetings can be the best part of the program.) Click here for mentor information.

C/ SOCIAL JUSTICE PROJECT

Typically scheduled for a Saturday evening in September

The pre-pandemic social justice project for the UU Church of Palo Alto was as follows:

Cook and serve dinner to Hotel de Zink, while this homeless shelter stays at UUCPA. N.B.: If there are more than 6 total Coming of Age participants, we split the group and serve dinner to Hotel De Zink on two different Saturdays.

An equivalent group social justice project may be substituted. The criteria for a good social justice project for Coming of Age: it should be hands-on; it should involve direct contact with persons being served; it should encourage positive human contact rather than “othering”; it should push the youth out of their comfort zone, while allowing shy youth to participate at their comfort level.

D/ LIFE-SIZED PLYWOOD SELF PORTRAITS

Typically scheduled for 2-3 Sundays in October and November

Session A: Participants start working on plywood sculptures, or continue working on them. This project usually takes 4-5 hours to complete, and there are five sessions devoted to it. The plywood sculpture project is an optional part of the Coming of Age program. Click here for information on making plywood sculptures.

Session B: Participants may start working on plywood sculptures, or continue working on them. Click here for information on making plywood sculptures.

Additional sessions to work on the plywood sculptures may be scheduled in the spring. If there are more than 6 or 7 participants, additional sessions may be needed to accommodate all the participants.

Unit 1: The Big Religious Questions

SESSION ONE: The Big Questions

Some big religious questions + talk about mentors + fun activities. This session is typically scheduled in mid-December, just before Christmas break.

I/ Check-in, attendance.

II/ Name game, icebreaker game (click here for games)

III/ Go over handout

Values voting: Point to two or more corners of the room for each of the values, and ask participants to head towards the corner that comes closest to what they think (and they may spread out along a continuum, or continua). Then when everyone is in place, ask why people furthest out are where they are, and then ask for any more explanations of why people are standing where they are standing.

a. What should I do with my life? Help myself — Help others

b. What’s the purpose of life? For me to be happy — For me to make the world better

c. What kind of being am I? Basically Good — Basically Evil — Other

d. What’s the nature of goodness? Whatever makes the most people happy — Whatever keeps the most people from suffering

e. Where does goodness come from? Goodness comes from human actions — Goodness comes from human ideas and ideals — Goodness comes from some place else (where?)

f. Where does suffering and evil come from? It’s random — It comes from people who hurt others — It comes from outside ourselves

g. What do I know what is true? I have to find it out for myself — I can’t find out everything for myself, so I have to trust others

h. Does my life have any meaning? Yes — No

i. Where does meaning come from in life? Meaning comes from what I do — Meaning comes from what I believe — Meaning comes from something else

IV/ Talk about mentors. Ask each participant if they have an idea for a mentor; if so, who is it; if not, say you will find a mentor for them.

V/ Closing circle: Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION TWO: “Who are you?” — The mirror project

Making mirrors to represent who you are. Typically scheduled in early January.

I/ Check-in, attendance.

II/ Business: Make sure everyone has mentors, and is meeting with them.

III/ Start making mirrors.

For instructions on how to make the mirrors, click here.

IV/ Closing circle: Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION THREE: Mirrors completed

Making mirrors to represent who you are (conclusion).

I/ Start right in working working on mirrors. Do check-in and talk about mentors or other business while working.

II/ With half an hour to go, tell people they have to be finished tonight!

For instructions on how to make the mirrors, click here.

III/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

Plywood sculptures, Continued

Additional time plywood sculptures can be scheduled between Units 1 and 2. This would typically take place over Martin Luther King Birthday weekend.

Unit 2: Religion and Existentialism

SESSION FOUR: What Is Religion?

In Coming of Age, we talk about what your religious identity is. But what do we mean by “religion”?

I/ Check-in, attendance

II/ Asking the question: What is religion? (Mini-lecture)

In Western culture, we mostly think that religion is all about what you believe. But scholar Ninian Smart says that belief is only one dimension of religion. He has listed a total of seven dimensions of religion:

1. The dimension of doctrine and philosophy, that is, what you believe

2. The dimension of ritual, that is, what you do together as a religious community

3. The dimension of narrative and myth, that is, what stories your religious community tells

4. The dimension of experience and emotions, that is, what you feel when you’re with you’re religious community

5. The dimension of ethics and laws, that is, what your religious tells you you’re supposed to do with your life

6. The institutional and social dimension, that is, how your religious group socializes together, and who your important people are

7. The material dimension, that is, what are the art works and buildings and ritual objects your religious community uses

Seven Dimensions of Religion (PDF)

Unitarian Universalism is a religion that doesn’t really care what you believe. But we do care a lot about what you do with your life. We think people should work to make this world a better place. And we Unitarian Universalists do care a lot about the institutional and social dimension of religion, because we think that it is VERY important that our congregations are democratically run.

Compare this with other religions. A religion like Judaism tends to emphasize following certain rules and certain moral teachings. Many Jews are not too worried whether or not someone believes in God, but they do care about keeping the Sabbath, attending services on the High Holidays, keeping kosher (esp. at Passover), and so on.

On the other hand, Christians and Muslims both care a LOT about what you believe. But both these religions also emphasize personal behavior. Muslims feel very strongly that they should follow certain rules, such as giving money to poor people. For their part, most Christians feel very strongly that the ritual of Communion (also known as the Lord’s Supper) is a very important ritual that every Christian should take part in.

III/ Discussion: the seven dimensions of religion for Unitarian Universalists

Now let’s apply these seven dimensions of religion to Unitarian Universalism. Which of the seven dimensions are most important to Unitarian Universalists?

1. The dimension of doctrine and philosophy (we believe that we should use reason to find out what is true, what else?)

2. The dimension of ritual (we meet once a week on Sundays, we light chalices, what else?)

3. The dimension of narrative and myth (what are the myths and stories we tell ourselves?)

4. The dimension of experience and emotions (what are the emotions that we share together?)

5. The dimension of ethics and laws (we know that we are supposed to make the world a better place, what else?)

6. The institutional and social dimension (democracy is very important to us; who are the most important people in our congregations? what else can you say about how we organize our congregations?)

7. The material dimension (what important art works, objects, or buildings do we have?)

IV/ The seven dimensions of religion for YOU

The seven dimensions of religion for YOU. Which are the most important dimensions of religion for you?

Many (but not all) Unitarian Universalists will say that the most important dimensions of religion for them, personally, is the ethical dimension, our responsibility to make the world a better place. Others will say the institutional dimension is most important, because we feel that (a) community is very important, and (b) democracy is very important.

What about you? Which dimensions are most important for you?

V/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION Five: Football Is Religion (Re-Defining Religion)

In the West, we tend to think that religion is somehow confined to churches and congregations. One of the big myths of the West is that religion is somehow separate from the rest of life. In this session, we will show how that myth is simply not true!

I/ Check in, attendance

Check with youth participant to see how much progress they have made on their statements of religious identity.

II/ Read a description of a religious ritual

Read out loud the following description of a religious ritual:

“As the sun rises over the crisp fall horizon, followers begin to gather in anticipation of the ritual that is about to take place. Individuals are dressed in their special colors, some wearing necklaces of their totem, while others wear headdresses that are adorned with their sacred symbol. People begin to drink [sacred intoxicating beverages], play music, and prepare a banquet feast for each other. They are creating a festival atmosphere in hope that today’s ritual will be a success.

“As the ritual draws near, the followers crowd into the sacred space. In that sacred space, they are surrounded with pictures and names of those who are remembered for their contributions to the sacred community. As the ritual begins, a special musical ensemble plays to bring everyone together and prepare for the events that are about to unfold.

“Those who perform the ritual take their place in the middle of the space, with onlookers surrounding them. Now that the ritual has begun the celebrants begin to perform and focus on their own actions in order to connect themselves with the sacred. The followers who look on aid those who perform the ritual by chanting. This chanting allows the onlookers also to achieve transcendence. Everyone does their part to make the ritual a success, up until the last second of the ritual is completed.

“It is only at the last minute that it can be decided if the ritual was a success. Persons wearing special black and white striped clothing make the final decision. It is only then the followers can either celebrate or grieve. This they do by singing their most sacred song, the song which bonds them once again with each other.”

Tell the participants that this is a description of a very common religious ritual in the U.S. Does anyone know what the religion is? Well, given the title of this session, obviously it’s football. More specifically:

“What initially seems to be a religious ceremony, as described above, is actually what happens at Ohio State Football games nearly every fall Saturday in Columbus, Ohio.”

This description comes from “Ohio State Football: It’s More than a Sport, It’s a Religion,” an honors research thesis by Nicholas Dominique, Ohio State University, 2011.

II/ Short open discussion

Now say: “Do you agree that American-style football is a religion?”

Allow some time for debate on this point, where you say as little as possible, except to get people to express their opinions.

III/ Defining religion

Then say: “If you say that football is NOT a religion, you have to define what religion is. AND if you say that football IS a religion, you still have to define what religion is. So — what is religion?”

You’ll probably hear someone say (or just write this definition on the flip chart): “Religion is belief in and reverence for a god recognized as the creator and governor of the universe” (based on the definition for religion in the American Heritage Dictionary). (If no one says this, you can just say it.) Write that on the flip chart, then cross it out. “That definition won’t work. Therevada Buddhists do not believe in a supernatural power, let alone in a god, yet Buddhism is clearly a religion.”

You’ll probably hear someone say (or just write this definition on the flip chart): “Religion calls on supernatural powers, which are believed to direct and control the course of Nature and of human life” (based on a definition by James G. Frazer). Write that on the flip chart, then cross it out. “That definition won’t work. Traditional Confucianism had little or no belief in supernatural powers, yet Confucianism is clearly a religion.”

Another obvious definition of religion: “Religion is the opposite of secular.” Write that definition on the flip chart, then cross it out. “That definition won’t work. There are tons of people who say that the U.S. is a Christian nation. We may disagree with them and say they violate the Constitution, but that doesn’t mean their definition of religion is wrong.”

Now turn to a new page on the flip chart. (Note: this next section requires a lot of writing on the flip chart, and you may want to write these definitions on a piece of flip chart paper in advance of the class, to save time.)

Write down another definition of religion: “Religion has churches (or the equivalent), priests (or the equivalent), and regular worship services. Religion requires belief in the supernatural.” Write that on the flip chart, and DON’T cross it out. Now say: “By this definition, football IS a religion. It has churches (the football stadium), it has priests (the players and coaches), and it has regular worship services (weekly football games). Football fans believe their team is better than any other team, which can only be described as a belief in something that isn’t true, or belief in the supernatural.”

Write this fairly long definition of religion on the flip chart: “Religion is (1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, persuasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in humans by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic.” This definition comes from anthropologist Clifford Geertz. Now say: “By this definition, football IS a religion. Football is filled with symbolism, it creates long-lasting moods in humans, and it provides a conception of the order of existence, while making it all seem completely realistic.”

Sum up by saying: “While it’s kind of humorous to think of football as a religion, there’s a serious side to this exercise. Now you can see that religion is not the same thing as belief in God.”

IV/ Defining religion from a UU Perspective

Say something like this: “(1) For us Unitarian Universalists, it’s clear that religion is NOT the same thing as belief in God. This is important, because about half of all Unitarian Universalists do not believe in God. (2) Therefore, it’s clear that for most Unitarian Universalists, religion is mostly concerned with something other than God.” Review Ninian Smart’s Seven Dimensions of Religion. Remind participants that we said most Unitarian Universalists are focused on ethics (what we do with our lives) and/or institutions (our communities).

Values voting:

Establish a linear continuum in your meeting room, with “Strongly Agree” on one side of the room, then “Agree,” then “Neutral” in the middle, then “Disagree,” and then “Strongly Disagree” on the other side of the room.

Now read the following statements. These are things that actual Unitarian Universalists have said when trying to define their religion. When you read one of these statements, ask the participants to move to a point on the continuum that represents their opinion. Then ask if anyone is willing to explain why they are standing where they are standing.

Being a good person is important to me.

Making the world a better place is important to me.

I want to work with other people to make the world a better place.

Music can be a religious experience for me.

Sitting quietly can be a religious experience for me.

Reading can be a religious experience for me.

I like to talk with others about the meaning of life.

I like talking about Big Questions with like-minded people.

When life gets hard, it’s important to me to have a supportive community.

Sum up this activity by saying something like this:

“For many Unitarian Universalists, God and traditional religion are NOT important. Instead, for many Unitarian Universalists, here’s what’s important — making the world a better place, making myself a better person, being part of a supportive community, participating in the arts.

“So what’s YOUR religion about? Is your religion about belief or non-belief in God? Or is your religion about making the world a better place? Or is your religion about finding a supportive community? Or something else? Or all of these things?”

Allow time for discussion. As the participants begin to articulate what’s important to them, point out that this is the sort of thing they can think about for their statements of religious identity.

V/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION Six: Existentialism

Hear a story by Jean-Paul Sartre, and decide whether you’re an existentialist or not.

I/ Attendance, check-in

II/ Read “The Wall” by Jean-Paul Sartre out loud. (This story is available on Google Books, as the first story in this book.)

III/ Discuss

Give a very short summary of existentialism. Key points:

- Existence comes before essence, i.e., there is no pre-existing meaning or essence in the world;

- If there is a God, God does not completely define the world for us.

- In this absurd world, we create meaning through our actions.

- You can’t not create meaning, since everything you do has some effect (as when the narrator gives a false place where Juan Gris is hiding).

- We are the sum of our actions.

IV/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

V/ Resources for the teacher .

(1) For more on existentialism, don’t waste your time on Wikipedia. Instead:

(a) Serious articles and books on existentialism abound. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has an exhaustive but difficult article on existentialism here — and the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, another peer-reviewed resource, has a similarly exhaustive essay here. The book “Is God a White Racist?” by Unitarian Universalist theologian William R. Jones is a classic of UU existentialism, but again challenging to read.

(b) For a shorter, more readable summary of existentialism, click here — then read “Introduction” and “Themes of Existentialism.”

(2) If you would like a shortened version of “The Wall” that can be read within the class time, please contact the curriculum author.

Unit Three: Religion in Arts and Literature

SESSION Seven: Unitarian Universalist poems

So what do Unitarian Universalists believe? Or do they believe anything at all? 3 poems to help answer these questions.

This session requires some advance prep by the teachers. You’ll need to read over the poems well in advance, and identify the Unitarian Universalist aspects of the poetry. Some teachers report that they find this session difficult to teach. Just remember that all you have to do is to look at the poems the way poetry is analyzed in high school English classes.

So the first thing you’ll want to do in class is read the poem out loud, with feeling, and so that it makes sense. (I recommend practicing this at home well before class.)

Second, make sure the participants understand what’s going on in the poem (e.g., “Let the Light Enter” is a poem about what it’s like to die, and what you might think about”). If the participants aren’t clear on what the poem’s about, read it out loud again. Get one of them to read it out loud.

The final step is to talk about how this poem might represent a UU viewpoint.

I/ Check in, attendance.

II/ Read several poems by UU poets and talk them over.

A. Pick 3 or more poems to discuss, based on the interests of youth participants. (Past experience shows that some groups will want to talk for a long time about just a few poems, while other groups will prefer shorter conversations about more poems Choose a poem to begin with.

B. Distribute copies of the poems to the participants, and ask for a volunteer to read the first poem aloud (if no one volunteers, no problem, one of the adults can read it aloud).

C. Lead a discussion of the poem. Here are some basic, open-ended questions that can apply to any of the poems (discussion questions specific to the individual poems are listed with each poem):

— What is going on in this poem? — or — What is this poem about? (We’re assuming here that there is no one single answer to either of these questions for any given poem.)

— In the Coming of Age program, we’re interested in the question “Who are you?” So who is the person speaking in this poem? What kind of person are they? Do you like this person or dislike them?

— Does this poem tell you anything useful about how you might live your life? Does this poem help you understand who YOU are?

D. Continue with the other poems you have chosen.

Below are some poems by Unitarian Universalist poets, (or in one case by a poet associated with UUism):

1. Let the Light Enter: The Dying Words of Goehte by Frances Ellen Watkins Harper

Harper wrote this poem over a hundred years ago, and it may sound old-fashioned. But this poem asks a question you might want to answer for yourself:

— What will you hope for when you are about to die?

— What do you believe will happen when you die?

“Light! more light! the shadows deepen,

And my life is ebbing low,

Throw the windows widely open:

Light! more light! before I go.

“Softly let the balmy sunshine

Play around my dying bed,

E’er the dimly lighted valley

I with lonely feet must tread.

“Light! more light! for Death is weaving

Shadows ’round my waning sight,

And I fain would gaze upon him

Through a stream of earthly light.”

Not for greater gifts of genius;

Not for thoughts more grandly bright,

All the dying poet whispers

Is a prayer for light, more light.

Heeds he not the gathered laurels,

Fading slowly from his sight;

All the poet’s aspirations

Center in that prayer for light.

Gracious Savior, when life’s day-dreams

Melt and vanish from the sight,

May our dim and longing vision

Then be blessed with light, more light.

Hints for teachers: Contrary to conventional Christians, Harper does NOT portray death as a moment when meet God. Nor does Harper use the old chestnut that “your life flashes before your eyes.” She claims that the dying poet wants “light, more light.” What might light mean in this context? Perhaps it’s related to “the light of reason”; that would certainly be a Unitarian viewpoint.

2. This Is Just To Say by William Carlos Williams

A piece of poetry trivia: Williams was fascinated by Chinese poetry, and in turn there are many Chinese poets today who are fascinated by Williams’s poetry.

Now for a straightforward question about this poem:

— Who is speaking in this poem, and to whom are they speaking?

Read the poem a second time. Say something like this: “The next poem seems very simple on the surface. Some guy eats some plums that someone else had put in the refrigerator. But when he eats the plums, he has a minor religious experience—he finds religion in small everyday moments. Equally important, that everyday religious moment has an impact on other people, that is, there’s an ethical side to his experience. For a very simple poem, there’s actually a lot going on!”

Hints for teachers: For me, this poem is about being present in the present world, the world of the senses. It is in the present world that we can find miracles — here, the poet experiences a minor miracle in the taste and pleasure of eating a plum. Yet the poet is not limited to the world of sensation; this poem describes a moment when he experiences transcendence. And even in the moment of transcendence, the poet is keenly aware of his connections to other human beings, in this case to the person whose plum he ate. This brief moment becomes a kind of religious experience, an epiphany if you will.

3. Now I Become Myself by May Sarton

Although Sarton never called herself a Unitarian Universalist, both she and Unitarian Universalists felt they had something in common (see this article for more).

— What do you feel is going on in this poem?

— What is the poet think is most valuable, or most important?

If the participants are confused by this poem, say something like this: “What does it mean to become yourself? How do you find out who you are? This poem explores these questions. Note that this poem was obviously written by someone who’s middle aged or older (‘It’s taken/Time, many years…’). Yet the poet is still exploring the same kinds of identity questions that you’re exploring as a teenager in Coming of Age. The search for your personal identity never ends.” Then read the poem again.

4. ‘Illegal’ Immigrants & Legal Humanity by Everett Hoagland

This is a “political poem,” that is, a poem that takes on charged political topics. Hoagland uses rhythms and rhyme schemes that feel like hip hop. Though (as the poet would be quick to point out) this style of poetry has deep roots that stretch all the way back into ancient West Africa.

— What problem is this poem trying to solve? And how does this poem tackle that problem?

— Can a poem make the world a better place?

Hints for teachers: Shouldn’t be too hard to figure out why this is a UU poem — UUs have long been committed to social justice.

If the participants don’t see this as a religious poem, you can say something like this: “Notice how the poet begins the poem by saying ‘…columbus came/in the name of God…’ and then later in the poem he talks about ‘…the pious [that is, religious] anglo pilgrims….’ Religion has always been intertwined with racism in the U.S. This is a religious poem because it confronts us with the ethical question of how the U.S. treats people of color—and how that affects our own self-identity, whether we are white people or people of color ourselves. The poem sounds like the ancient Biblical prophets who used scorn and anger to remind people that (a) they are behaving badly, and (b) they can behave better.”

5. Ella Mason and Her Eleven Cats by Sylvia Plath

Plath wrote what is called “confessional” poetry — that is, her poems tell about her deepest feeling and inmost thoughts. It’s also worth knowing that she had a troubled marriage.

— At the end of this poem, Plath seems to say that for women marriage is not as good as being single. Agree or disagree, and why?

— What do women have to give up when they get married?

Hints for teachers: I would consider this a feminist poem, and that’s part of what makes it a UU poem. More importantly, the poem tells how Ella Mason remained true to her own self, true to her identity, regardless of what the world thought about her. And by remaining true to her own identity, she avoided the falseness that can come from thoughtlessly following social conventions.

Sometimes the participants need prompting to understand that this is both a feminist poem, and a poem about self-identity. If so, you can say something like this: “In this poem, Ella Mason seems a little strange. She chooses to live her life the way she wants to, without conforming to social norms—in particular, she refuses to get married. Yet by the end of the poem, it becomes clear that maybe she has made the best choice. Some women who get married find that they have to give up part of their self-identity, but Ella Mason is able to remain true to her self identity. In the end, the poet lets you decide which is better: to be strange and have people laugh at you, or to hold on to your self identity.”

6. “Each in His Own Tongue” by William Herbert Carruth

The wording of this poem may sound a little bit old-fashioned, but it says something that most UUs still find to be true: what is traditionally called “God” can also be expressed in other ways, such as science, social justice work, etc.

A fire-mist and a planet,—

A crystal and a cell,—

A jelly-fish and a saurian,

And caves where the cave-men dwell;

Then a sense of law and beauty,

And a face turned from the clod,—

Some call it Evolution,

And others call it God.

A haze on the far horizon,

The infinite, tender sky,

The ripe, rich tint of the cornfields,

And the wild geese sailing high,—

And all over the upland and lowland

The charm of the goldenrod,—

Some of us call it Autumn,

And others call it God.

Like tides on a crescent sea-beach,

When the moon is new and thin,

Into our hearts high yearnings

Come welling and surging in,—

Come from the mystic ocean

Whose rim no foot has trod,—

Some of us call it longing,

And others call it God.

A picket frozen on duty,—

A mother starved for her brood,—

Socrates drinking the hemlock,

And Jesus on the rood;

And millions who, humble and nameless,

The straight, hard pathways plod,—

Some call it Consecration,

And others call it God.

Hints for teachers: This poem may be very challenging to some participants. Many youth today have internalized the assumption that science and God cannot be reconciled. Carruth states quite clearly that he thinks evolution and God can be considered one and the same thing. While the participants may argue violently against Carruth, you’ll just have to tell them that for many people this remains true; e.g., there are many scientists who are also religious Christians who believe in God.

You may choose to add this commentary to the poem: “First published in 1895, this poem was considered radical because the poet declares that God is the same thing as Evolution. In other words, science and religion are two equally valid ways of looking at the world. Today, this is still a radical poem because many people dismiss God and traditional religion in favor of science and evolution. Yet there are many working scientists who belong to traditional religions. And there are non-traditional religions, like Unitarian Universalism, where many people agree with this poem—religion does not have to be antagonistic towards science.”

III/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION Eight: Intro to Western religious practice

Unitarian Universalism came out of the Western Christian tradition. Western Christianity is a religion that values books and reading. In this session, we look at the Religion of the Book!

I/ Check in, attendance.

II/ Intro to the Bible (show and tell)

- Show a Bible

- Show the parts of the Bible: Torah, Prophets, Christian scriptures, etc.

- The Bible is not ONE book, it is actually a COLLECTION of books!

- Point out the books of the Bible that UUs like best: Ecclesiastes (kind of existentialist), Song of Songs (which we usually interpret as a sexy love poem), Mark (the earliest story of Jesus)

- Mention that many books got left out of the Bible, and mention that there are books that are not in every Bible

We UUs don’t take ANY book or text as literal truth, reading is ALWAYS a conversation or an argument. So we tend to think of the Bible as a collection of books which do not necessarily agree with each other, and which represent different views on what it means to be human, and what it means for humans to have a relationship to something larger than themselves. In other words, from a UU point of view, the whole Bible is kind of like a big argument or discussion.

III/ Prayer is spiritual practice centered on words

Prayer is perhaps the most distinctive Western religious practice. Traditional Christians see prayer as a way of getting to know their God. But for us Unitarian Universalists, what’s interesting is that prayers use words. Unlike Eastern forms of meditation, that typically require you to empty your mind of everything (including words), Western prayer asks you to focus on words.

Here are some types of prayer:

- prayer as meditation (when we try to empty our minds of everyday things), usually done by focusing on a short phrase, or even one word

- prayer as a call for social justice, usually spoken out loud, calling for the world to become a better place

- prayers as arguments — for example, meditating on on a question like: “why is the universe so stupid and perverse?” OR some people may argue directly with a deity, especially when they think the deity has screwed up the world

- prayer as a way of caring for others, usually done by saying out loud what problems people are facing (like “Caring and Sharing,” also known as “Joys and Sorrows”)

- prayer as a way of asking the universe for personal favors (like when you say: “I pray that I can pass this test!”)

IV/ A prayer technique to try: centering prayer

A. Choose a sacred word, or a sacred text, that you will concentrate on. Some good choices for Unitarian Universalists:

“one” — a word which affirms the ONEness of all existence

“all” — a word which affirms that ALL persons are worthy of love

“Love your neighbor as yourself.” — from the Hebrew Bible (Lev. 19:18), later repeated by Jesus and Rabbi Hillel

“Know yourself.” — an ancient Greek saying, often repeated by Socrates

“Simplify, simplify.” — Henry David Thoreau, Walden

B. Sit somewhere where you can be comfortable and quiet for 10-20 minutes. Close your eyes, or focus on something like a candle flame. Slowly repeat the word or phrase that you have chosen, as a way to symbolize that you want to allow this thought or phrase to become active within you. You could repeat one of the words each time you breathe out; or you could repeat the phrases every second or third breath.

C. Distracting thoughts usually pop up when you are doing this. No problem: let yourself become aware of those distracting thoughts, then gently return to the word or phrase.

D. At the end of the time you have set aside for centering prayer — ten minutes is plenty of time to begin with — just sit in silence for a few moments, slowly open your eyes, and gradually come back

These words or phrases are associated with books or larger religious concepts. So the word “one” is a a shorthand way of affirming Unitarianism, and the word “all” is a shorthand way of affirming Universalism. The three phrases give key bits of wisdom from books of religion or philosophy: the Hebrew Bible, the works of Plato, Thoreau’s Walden. This is worth knowing, in case some day you wish to go deeper into these religious concepts or these books of philosophy.

How to time yourself: it’s probably best to glance every once in a while at a clock or watch — for most people setting an alarm would be a second choice since alarms can be shocking when they go off. If you do this regularly, you will soon know when ten or twenty minutes is up, and you will only have to glance at the clock or watch once or twice.

V/ Closing circle

Remind youth that next session is a field trip. Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

Session Nine: Field Trip To See Asian religious art

In this lesson, participants look at some Asian representations of the divine, including art by Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, Sikhs, Taoists, etc. Ideally, the field trip will introduce the participants to deities, semi-divine beings, religious exemplars, and figures from myth.

On the field trip, participants may either stick with the leader of the tour, who will show various interesting objects, or they can go on a scavenger hunt.

Sample instructions for a scavenger hunt.

Logistics:

At UUCPA, we try to schedule this field trip for the first Sunday of the month (typically March), because the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco has free admission that day. Otherwise, you’ll want to put money in your budget to pay admission for those who can’t afford it.

For the UU Church of Palo Alto, leave the church parking lot at 9:30 a.m., arrive at museum 10:30 a.m. (allowing time to park in the parking garage).

Once in the museum, tour the exhibits for approx. 1 hour

Option: stay for lunch at the Asian Art Museum Cafe (the cafe offers excellent pan-Asian food).

Return to UUCPA at 12:30, or at 1:30 if you stay for lunch

Hints for teachers:

Making the scavenger hunt handout: You will need to visit the museum a couple of weeks in advance of the field trip. Go through the museum, and find religious art from several different religions and/or cultures. Try to find art works that depict deities, semi-divine beings, mythical beings, and human exemplars of religion. Use the sample instructions for a scavenger hunt as a guide for what kinds of things to look for.

The field trip is easier if one of the teachers is someone who is familiar with Asian religious art. But honestly, you can become enough of an expert yourself by taking the time to read the gallery labels for the art works. Look for labels that offer some background information about the subject of the art work. Read the labels carefully. Take photos of the label and the art work, so you can remember all the info when you get home and are making up the scavenger hunt.

Plywood sculptures, Concluded

At about this point in the curriculum, schedule one last chance to work plywood sculptures (this is often scheduled over school spring break). If not done this week, you can either arrange a time to finish them, or take them home to finish them. (It’s OK if you do not finish them.)

Unit Four: Writing Statements of Religious Identity, Planning Worship

SESSION Ten: How To Write Statements of Religious Identity

Introduction to writing statements of religious identity, with time to work on them. Mentors are most definitely invited!

I/ Check in, attendance

II. Ask each youth participant how statements of religious identity are coming (mostly, no one will have done much).

III/ Hand out packet of sample statements of religious identity. Go over the handout. Explain that there are two basic methods for writing statements of religious identity:

(a) The list method, where you list what you affirm, one paragraph on each belief or affirmation

(b) The story method, where you tell a story that illustrates a key part of your religious identity

IV/ Break into small groups. Adults get youth to start talking about what their statement of religious identity is going to say. Often, youth will come out with a nice opening sentence or paragraph — stop them, and get them to write it down while it’s still fresh. Then let the conversation flow. Expect to get into some pretty deep conversations!

N.B.: statements of religious identity will generally be written statements, but sometimes youth with particular talents will use another medium. Youth who find it impossible to read their own statements of religious identity out loud (shyness, language barrier, etc.) can ask their mentor or a minister to read their statement for them.

N.B.: Encourage youth to keep their work-in-progress online somewhere (e.g., Dropbox, Google Drive, etc.). This makes it easier to work on the statements of religious identity during class time. However, if they prefer to write by hand, that’s totally fine!

V/ Closing circle: Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION Eleven: Practical religion

Most religions are not democratic, but UUCPA is. This is a chance for you to think about whether you think religion should be democratic or not!

N.B.: This session is placed here in order to give the participants another week to work on their statements of religious identity at home. This session fits in better with Unit 2, but we’ve found that the participants appreciate having a change of pace at about this point in the curriculum, so we’re leaving it here.

I/ Check-in, attendance

II/ The institutional and social structure of our faith community

Quick look at how organized religions can be run: hierarchy (Roman Catholics, Episcopalians); consensus (Quakers); anarchy (some neo-pagans); spiritual leaders who are in essence autocrats (such as gurus, yoga teachers); representative democracy (UUA).

Overview of our congregation’s democracy: the annual meeting and what members do; how you can become a member of our congregation; how Board members are elected, and what they do to run our congregation; what the ministers do. (Compare and contrast our congregations’s democracy to other ways of organizing a faith community.)

Note that the institutional & social structure of our congregation is almost exactly the same as it is in many Baptist churches. Yet the Baptists are definitely Christian, and we are not. In other words, the institutional structure and the doctrines of a religious community are separate things. (Review Session Four.)

III/ Panel discussion

Get representatives from the Board, the Committee on Ministry, and the Worship Associates to each talk about what they do. Each of these groups has youth members, so the panel might include both a youth and an adult from each group.

IV/ Closing circle

Remind the participants that they should be working on their statements of religious identity, and that they should bring whatever work they have done to the next class.

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION Twelve: Time to work on Statements of Religious Identity

Time to work on statements of religious identity. Mentors are most definitely invited!

I/ Check in, attendance

Check with youth participant to see how much progress they have made on their statements of religious identity.

II/ Break into smaller units as follows:

- If mentors are present, those mentors and their youth work together.

- Teachers may pair up youth to work together, or each teacher may works with small groups of youth themselves.

- Some youth will want to work alone.

III/ Closing circle

Remind youth that next session we will attend a worship service at UUCPA, then stay late to discuss it. Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION Thirteen: Attend the worship service

(N.B.: This class should be scheduled so that the minister can meet with the youth after the service for about 15 minutes, and talk about how they planned that week’s service.)

Since the youth will soon be leading the service, this is a chance to attend a UUCPA service and see what it’s like. The youth will meet with the worship leader and/or a worship associate afterwards to talk over how they plan the service.

I/ Attend service

II/ Meet in regular room, quick check in and attendance (while waiting for the senior minister)

III/ Meeting with the worship leader(s)

- What did they think about when they planned this service?

- What did they think about as they wrote this sermon (or reflection, in the case of the worship associate)?

- What are the words they use to introduce the various parts of the service (hymns, offering, etc.)?

IV/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

No Coming of Age on Easter

SESSION Fourteen: Planning the Service

During this session, we plan the Coming of Age service. All youth should bring an outline, or early draft, of their statement of religious identity to this class.

I/ Check in, attendance

II/ This class is devoted to planning the Coming of Age service.

a. The teacher will have hymnals for everyone.

— Choose hymns. (The youth participants can try to choose topical hymns, but often they like to choose hymns that they know and like.)

— Choose opening words, chalice lighting words, etc.

b. Next, the teachers pass out a handout with a fully scripted order of service, showing the wording for everything (i.e., what do you say when you introduce the hymns, what do you say during the offertory, etc.).

— Go through the entire order of service.

— Decide who will lead each piece (i.e., who will do announcements, who will introduce hymns, etc.).

— Decide the order in which the statements of religious identity will be read. Have each youth talk about their statement (that’s why they need a first draft). Often there is a statement of religious identity that sounds like a great way to start the service, and often there is a statement of religious identity that sounds like a good way to close the service. And/or, just talk about who wants to go first, who wants to go last, etc.

c. We have found it helpful to create a shared document online (e.g., Google Doc) that all the youth participants can view.

III/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

SESSION Fifteen: REHEARSAL

During this session, we do a complete run-through of the whole service. Do NOT miss this rehearsal, because we will show youth the easy way to look and sound fantastic!

I/ Attendance, intro.

II/ Read this poem by Everett Hoagland that describes what a UU service can do: lifting people “beyond belief,” getting them to think and feel and be in new ways, instead of remaining stuck in the same old ways. Now, go through the standard order of service, and figure out who will do which pieces. Have hymnals available to choose opening words, hymns, etc.

III/ BRIEFLY talk about reading statements of religious identity. Emphasize that we want the youth to look comfortable, and we want them to sound great.

We have found that the following basic guidance leads to the best performance:

- To look comfortable, put your hands on the pulpit (even lean on the pulpit if you’re tall enough). This will keep your hands out of your pockets, fumbling around, etc. And you will look relaxed and confident.

- To look even better, if possible look up from your paper every now and then and make eye contact with the people listening to you. They will be impressed if you do.

- To sound great, speak more slowly than you think you should (talk as if you’re talking to someone who is hard of hearing, because you probably will be talking to people who are hard of hearing, and they want you to go slow so they can understand).

- To sound even better, speak more loudly than you think you should (talk to the people in the back of the room).

Have youth read their entire statement of religious identity, using the microphone. Ideally, there will be time to run through all statements of religious identity twice. Adults remember: we get best results if we are not overly critical, but instead emphasize what the youth do best! But do remind youth of the basic rules above:

— Hands on pulpit

— If you can, look up now and then

— Speak ssslllooowwwwlllllyyyy

— Speak to the back of the room

GIVE POSITIVE FEEDBACK TO EVERY YOUTH FIRST! They need, above all, to hear what they are doing RIGHT. Then, and only then, COACH them on these four basic points: hands on pulpit, look up if possible, speak slowly, speak loudly.

If needed, show youth how to print their statements of religious identity in LARGE FONTS. They should make sure statements of religious identity are in a binder (or at least stapled together).

IV/ Figure out where people are going to sit behind the pulpit.

Now run through the whole service, including lighting the chalice, announcing hymns, offering, other transitions, etc. (you don’t have to have youth read statements of religious identity again,but do have them stand up when it is their turn to read their statement of religious identity).

V/ Closing circle

Everyone says one thing that stood out in today’s session. Then say the Unison Benediction together.

no Coming of Age on MOther’s Day

FINAL SESSION: Coming of Age service and lunch

Youth lead both services, at 9:30 and 11:00

Afterwards, potluck lunch from 12:30-1:30. There will be time right after lunch for parents to sit down with their child and tell them how fabulous their child is.

Former Session Two: “God Talk”

This session is no longer included in the curriculum, but remains here for those who wish to use it.

In our culture, religion is associated with “God.” But what do you think “God” is? Is God even necessary for religion? Pass out the God Talk checklist, and go over it briefly to make sure everyone understands it. Ask participants to think about the checklist on their own, circling their preferred responses and making notes as needed. Put participants into pairs (add a trio if an odd number of participants; at this point it’s best for adult leaders to pair up with each other, not with young people) to talk about their reactions to the checklist. Then pairs report back in to the whole group: “Say what you or your partner said that was most interesting to you.” After pairs report in to the whole group, the adults can go over the checklist and point out some of the Unitarian and Universalist theologies behind some of the statements. Here’s a cheat sheet summarizing some of these theologies:

GOD-TALK CHECKLIST CHEAT SHEET

Unitarian and Universalist theologies behind the statements in Part I, listed in order:

— generic liberal theology

— classic Universalism

— classic Unitarianism

— classic liberal theological emphasis on the use of reason in religion

— a typical argument of classic Universalism

— William R. Jones and Charles Hartshorne use sophisticated versions of this argument

— a typical argument of process theology

Unitarian and Universalist theologies behind the statements in Part II, listed in order:

— this statement would be counter to most UU theology

— classic second-wave feminist theology

— a common theme of classic Unitarianism and Universalism

— definitely a belief of many early nineteenth century Unitarians and Universalists

— a version of deism

— classic Latin American liberation theology

— similar to the religious naturalism of Thoreau and the later Bernard Loomer, and perhaps related to twentieth century ecofeminists

— pantheism or panentheism, held by such UU figures as Abner Kneeland

— an argument of some humanists, e.g., Charles Lyttle

— some later Universalists would agree with this