From Many Lands

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2019 Dan Harper

2. PLANTING A PEAR TREE

One day in the marketplace, a man from the countryside was selling pears he had grown. These pears were unusually sweet with a fine flavor, and so the countryman asked a high price for them.

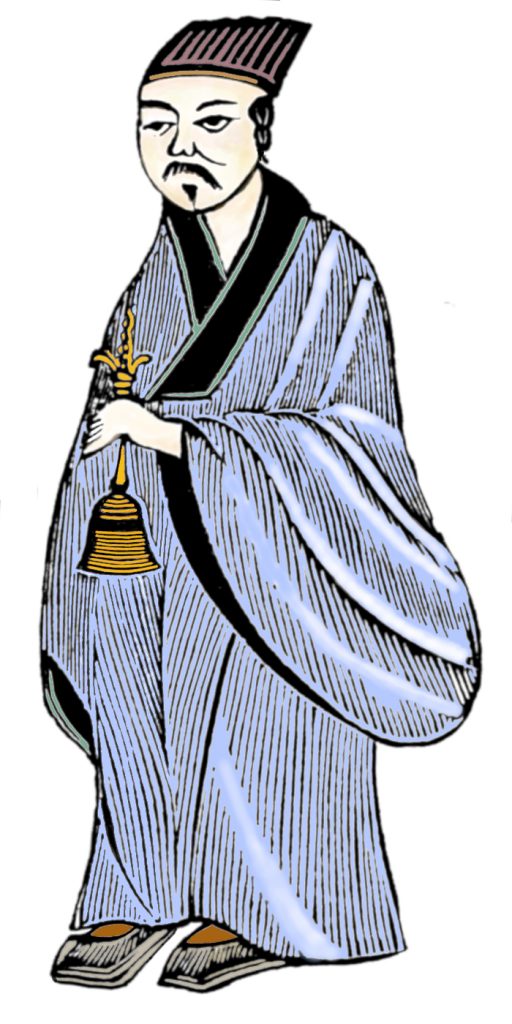

A Daoist priest, dressed in a ragged old blue cloak, stopped at the barrow in which the countryman had displayed these lovely pears.

“May I have one of your pears?” he said.

The countryman said to him, “Get away from my barrow, so that paying customers may buy my pears.” For the countryman knew that the priest expected him to give him one for nothing. But when the priest did not move, the countryman began to curse and swear at him.

The priest said, “You have several hundred pears on your barrow. I ask for a single pear, the loss of which you would not feel. Why then, sir, do you get angry?”

Several people who were standing around told the countryman to give the priest a pear that was bruised, or which had some sort of blemish, a pear that he could not sell anyway. If he would only do that, then the priest would go away. But the countryman was stubborn, and he refused to give the Daoist priest anything at all.

The beadle of the town, who was charged with keeping the peace and maintaining order, came over to see what was going on. This beadle saw that things were getting out of hand, so he purchased a pear from the countryman, and presented it to the Daoist priest.

The priest bowed low to the beadle, thanking him for the pear. Then the priest turned to the crowd who had gathered round, and said, “Those of us who are Daoist priests have left our homes and given up all wealth. So when we see selfish behavior, it is hard for us to understand it. Now as it happens, I have some pears with a very fine flavor, and unselfishly I would like to share them with you.”

Someone in the crowd called out, “But if you have pears of your own, why didn’t you just eat one of them? Why did you have to have one of the countryman’s pears?”

“Because,” said the priest, “I wanted one of these seeds to grow my pears from.” So saying, he ate up the pear that the beadle had given him. When he had finished eating, he took one of the seeds, unstrapped a pick from his back, and bent down to make a hole in the ground, four inches deep, with the pick. Then he dropped the seed into this hole, and filled it in with earth. Turning back to the crowd, he said, “Could someone bring me a little hot water, please, with which to water the seed?”

One among the crowd who loved a joke went into a neighboring shop and fetched him back some boiling water.

The priest poured the boiling water over the place where he had made the hole. Everyone watched closely, for though it seemed like a joke, Daoist priests were supposed to have knowledge of alchemy and magic and the mystical arts.

Suddenly the people in the crowd saw green sprouts shooting up out of the ground, growing gradually larger and larger until they became a tree. This pear tree — for it was, indeed, a pear tree — quickly grew in the spot, and sprouted green leaves, and then put forth white flowers. Bees were heard buzzing among the flowers, then the petals dropped, and before long the tiny hard green fruits had grown and ripened into fine, large, sweet-smelling pears which hung heavy on every branch.

The priest picked these fine pears and handed them around to everyone in the crowd. When at last everyone had a pear, and all the pears had been picked from the tree, the priest turned and with his pick he hacked away at the tree until, after a long time, he cut it down. Picking up the tree and throwing it over his shoulder, leaves and all, he walked quietly away.

Now this whole time, the countryman had been standing in the crowd, straining his neck to see what was going on, and forgetting all about his own business. When the priest walked away, he turned back to his barrow and discovered that every one of his pears was now gone. He then knew that the pears that old fellow had been giving away were really his own pears. And when the countryman looked more closely at his barrow, he saw that one of its handles was missing, for it had been newly cut off.

Boiling with anger, the countryman set off after the Daoist priest. But as he turned the corner where the priest had disappeared, there was the lost wheel-barrow handle lying next to a wall. It was, in fact, the very pear tree that the priest had cut down.

But there were no traces of the priest — much to the amusement of the crowd in the market-place, who watched the countryman’s rage as they finished eating their sweet, juicy pears.

Source: Adapted from Pu Songling, trans. Herbert A. Giles, Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (London: Thomas De La Rue & Co., 1880).

A Doaist priest (adapted from a public domain image from Hampden C. DuBose, The Dragon, Image, and Demon [New York: Armstrong & Son, 1887]).

SESSION TWO: “Planting a Pear Tree”

Top-level educational goals:

(1) Have fun and build community;

(2) Increase religious literacy;

(3) Build skills associated with liberal religion, e.g., interpersonal skills, introspection, basic leadership, being in front of a group of people, etc.

Educational objectives for this session:

(1) Get to know other people in the class;

(2) Hear a story from this religious tradition;

(3) Be able to talk about one or more incidents or themes from the story, e.g., if parents ask what happened in Sunday school today.

Optional advance preparation:

If you’re stuck for time, you can teach this class with only a few minutes preparation. If you have time to do advance preparation:

a. Print out copies of the Daoist Priest coloring page (PDF)

b. Buy a couple of pears to cut up and share

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story “Planting a Pear tree.”

Read the story above.

If you would like to give the children something to do while listening to the story, the illustration for the story can be printed out and used as a coloring page.

III/ Act out the story.

As usual, we will help the children internalize the story by acting it out. Some of the children may be familiar with how to act out a story, but others won’t be. This is a simple story to act out, and a good way to help the class (children and adults!) build the skills needed to act out a story.

Ask: “Who are the characters in this story?” In this story, the main characters are the Daoist priest, the person selling pears, the “beadle” (sort of like a police officer), the person who runs to get water, plus all the villagers. So there is a role for everyone!

Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with the lead teacher; you will sit facing the stage.

The lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. Actors do not have to repeat dialogue, although some of them will want to do so. The lead teacher may wish to simplify the story on the fly, to make it easier to act out.

Since this is such a simple story, you may want to act it out twice, with different sets of lead actors each time.

Fill the bulletin board in your classroom! It would be great to take photos, print them out later, and post them on the bulletin board in your classroom.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group. Now ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

One of the key elements in the story is the magical growth of the pear tree. As it says in the story, Daoist priests were popularly believed to do all sorts of magical things. Ask the children: “Do you think the Daoist priest could really make a pear tree grow from a single seed?” Accept whatever variety of answers you may get for now. Next, here are some more questions you can ask: “How did the Daoist priest get the handle of the wheelbarrow without the pear-seller noticing?” “How could the priest make a wheelbarrow handle into a tree?” “Why did the tree turn back into a wheelbarrow handle?” “How did the Daoist priest disappear at the end of the story?” By now, it should be clear that the magical elements of this story are very magical indeed, and maybe don’t even really make sense!

So — is this story true, or not? Ask the children: “Is this story really true, or is it more like a fairy tale?” Most of them will say this story is more like a fairy tale. “If this story is more like a fairy tale, does it have a moral?” The children should figure out pretty quickly that the story is about not being selfish. Then you might repeat what the priest says during the course of the story: “Those of us who are Daoist priests have left our homes and given up all wealth. So when we see selfish behavior, it is hard for us to understand it.”

If you would like to, you can have a brief conversation about selfishness. The Daoist priest says that he has a hard time understanding selfish behavior, and you could ask the children: “Do you understand why people are sometimes selfish?” And maybe the children would like to give examples of when they have seen people being selfish.

V/ Sharing pears OR drawing pictures

If you brought a couple of pears, you can bring them out now. One way not to be selfish is to share, and you can demonstrate this (with whatever explanations you want to give) by cutting up the two pears to share with all the people who are present in class.

OR if you didn’t bring pears, you can have the children draw pictures to illustrate the story. What did it look like when the pear tree grew up out of a little seed? — or whatever else the children want to draw.

VI/ Free play

If you need to fill more time, have some free play time. Free play can help the class meet the first educational goal, having fun and building community. Ideas for free play: free drawing; “Duck, Duck, Goose”; play with Legos; walk to playground or labyrinth (if time); etc.

VII/ Closing circle

When time is almost up, have the children stand in a circle by touching toes, or touching elbows.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about a Daoist priest and some pears, right?” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

Say the closing words together — either these words, or others you choose:

Go out into the world in peace

Be of good courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return no one evil for evil

Strengthen the fainthearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Rejoice in beauty

Speak love with word and deed

Honor all beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

LEADER RESOURCES AND BACKGROUND:

1. Source of the story

This story was adapted from from a story by Pu Songling (1640-1715), from his masterpiece Liaozhai zhiyi, translated by Herbert A. Giles as Strange Stories from a Chinese Studio (London: Thomas De La Rue & Co., 1880). Pu Songling finished writing this book around 1679.

2. More about Daoism

Many people in Western society are most familiar with Daoism (also Anglicized as Taoism) as a philosophical system presented in the book the Daodejing (also Anglicized as the Tao To Ching). But the religion of Daoism is much more than a single book; it has its own temples, rituals, priesthood, gods and goddesses, etc. The BBC says of Daoist rituals that they

“…involve purification, meditation and offerings to deities. The details of Taoist rituals are often highly complex and technical and therefore left to the priests, with the congregation playing little part. The rituals involve the priest … in chanting and playing instruments… and also dancing.” (link)

Harvard University’s Pluralism Project notes that there is “immense diversity within the tradition” of Daoism. While Westerners are probably most familiar with the philosophical tradition of Daoism, there are also alchemical traditions within Daoism, in which individuals try to achieve immortality through drinking elixrs such as “potable gold.” Other traditions within Daoism focus on meditation, gymnastics, pharmacology, etc. The Pluralism Project has a series of excellent short essays about Daoism in general, and Daoism in the West — link.