Games for UU kids and adults

Compiled and written by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

Blackbird Migration

Food Chain Game

Lynxes, Hares, and Leaves

Moksha Patam

Lynxes, Snowshoe Hares, and Leaves

From the Ecojustice Outdoors Book 5th ed., copyright (c) 2024 Dan Harper. All rights reserved.

The Referee divides the players into Lynxes, Snowshoe Hares, and Leaves. If you have 10 players, you’ll need 4 Hares, 4 Leaves, and 2 Lynxes.

— Leaves stand still with hands up at shoulder level (as if about to give a high-five)

— Hares have tails (pieces of white cloth to stick into back pocket, like flag football)

The play area is a big circle. Hares have a Warren (a square of felt on the ground). They are safe from the Lynxes as long as they are touching the felt.

At the start of each round:

— The Hares all touch the Warren

— The Leaves stand in a broad circle around the Warren

— The Lynxes stand near the Leaves

When the Referee gives the signal to begin a round:

— Leaves cannot move from their spot, and as soon as a Hare eats them, they must put their hands down.

— Snowshoe Hares must leave the Warren to “eat” Leaves — they eat by giving one Leaf a high five. Hares may eat only one Leaf in each round. Hares are safe and cannot be tagged when they are touching the Warren OR when they are frozen in a crouched position — this means that Hares may not move or get Leaves unless they are standing up. Hares must eat in each round, or they will die from hunger.

— Lynxes try to “eat” a Hare by pulling off their tails. Lynxes must eat in each round, or they will die of hunger. Lynxes may eat only one Hare in each round.

A round lasts 3-5 minutes. At the end of the round, the Referee calls out “End of Round!” and all action stops.

— If a Leaf has been eaten by a Hare, that Leaf becomes a Hare in the next round.

— If a Hare has been eaten by a Lynx, that Hare becomes a Lynx next round.

— If a Hare has not eaten a Leaf in that round, that Hare dies, rots away, turns into compost, and becomes a Leaf in the next round.

— If a Lynx has not eaten a Hare in a round, that Lynx dies, rots away, turns into compost, and becomes a Leaf in the next round.

Ecosystem Crash

This game shows that when there are too many predators, the predators will not have enough to eat and some will starve to death. And if there are too many plant-eaters (herbivores), they will not have enough to eat.

It sometimes happens that all of one of the organisms — lynxes, hares, or plants — dies. If one organism dies off, pretty soon all the other organisms will die off, too. We call this an “ecosystem crash.”

In this game, there are two ways the ecosystem can crash. If all the Hares die off one round, then all the Lynxes will die off in the next round (be-cause the Lynxes will have nothing to eat), and then everyone will be a Leaf in the round after that. If all the Lynxes die off in one round, more and more Hares will be born, until pretty soon the Hares eat all the Leaves, at which point they will die off.

Evolution and Adaptation

In the real world, some hares will be born with a fur color that makes it easier to hide from predators. Because they can hide a little bit better than other hares, they are a bit more likely to have babies. And they may pass along their fur color to their babies. Over time, more and more hares will have the new fur color. When this happens, the lynxes will have a harder time catching enough hares to eat.

You can try this in the game. When you first start the game, do not allow hares to be safe when they are frozen in a crouched position. Then after playing a few rounds, start allowing hares to be safe when frozen in a crouched position. What happens?

In the real world, if the hares evolved to get better at hiding, eventually the lynxes would evolve to become better hunters. Think about what rule you could add to the game so the lynxes get better at hunting.

Another Game: Humans, Lynxes, Hares, & Leaves

What happens if we add Humans to this game?

If you have 12 or more players, you can add a Human. The Human can kill and eat any other creature (Leaf, Hare, and Lynx). The Human cannot be killed by any other creature. The Human can kill as many creatures as they want during any round.

With this rule, the ecosystem can crash very quickly.

The Science Behind the Games

For over a hundred years, people working for the Hudson Bay Company in Canada kept records about the populations of lynxes (Lynx canadensis). In 1942, two scientists named Charles Elton and Mary Nicholson showed how the number of lynxes rose to a peak about every ten years, then quickly diminished. Elton and Nicholson wrote: “This cycle is a real one in lynx populations, which are dependent upon the snowshoe hare for food, and which starve when the hares disappear periodically. It is therefore strong evidence of a similar cycle in snowshoe hares.”

Later, four other scientists — Charles J. Krebs, A. R. E. Sinclair, Rudy Boonstra, and Stan Boutin — showed that the relationship between lynxes and hares is more complicated than Elton and Nicholson believed. In fact, lynxes and hares are connected with every other organism in the forest where they live. These four scientists also say that humans can cause such big changes that the populations of lynxes and hares could both collapse.

Processing the game: Interdependence

What can the Human do to keep the ecosystem from crashing? Or think about this question — What would happen if the Lynxes started killing more Snowshoe Hares than they needed for food?

If the Lynxes killed too many Snowshoe Hares, pretty soon the Snowshoe Hares would die out. Then the Lynxes would have nothing to eat, and they would starve to death. But the Snowshoe Hares also depend on the Lynxes. If there were no animals that ate Snowshoe Hares, more and more Snowshoe Hares would be born. All those Snowshoe Hares would eat up all the vegetation, and then they would have nothing to eat, and they would die.

We Human Beings have to remember that we, too, depend on other living things to stay alive. We have to remember that we should only kill just enough plants and animals to keep us alive.

Notes: “Lynxes, Rabbits, & Leaves” is derived from a game learned from environmental educator Steve van Matre, called “Foxes, Rabbits, Leaves.” The scientists referred to in this chapter: Charles Elton and Mary Nicholson, “The Ten-Year Cycle in Numbers of the Lynx in Canada,” Journal of Animal Ecology, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Nov., 1942), pp. 215-244. Charles J. Krebs, A. R. E. Sinclair, Rudy Boonstra, and Stan Boutin, “What Drives the 10-year Cycle of Snowshoe Hares?” January, 2001 (Vol. 51 No. 1), BioScience, pp. 25-35.

The Food Chain Game

From the Ecojustice Outdoors Book 5th ed., copyright (c) 2024 Dan Harper. All rights reserved.

Background for the Food Chain Game

A food chain starts with energy from the Sun. Green plants use the energy from the sun to make food in the form of carbohydrates. Then animals eat the plants, and other animals eat those animals, and so on up the food chain. Now imagine a food chain with four organisms.

First there are Grass Plants (Poaceae spp.). Plants convert the Sun’s energy into food. In a food chain, we call them producers because they produce food.

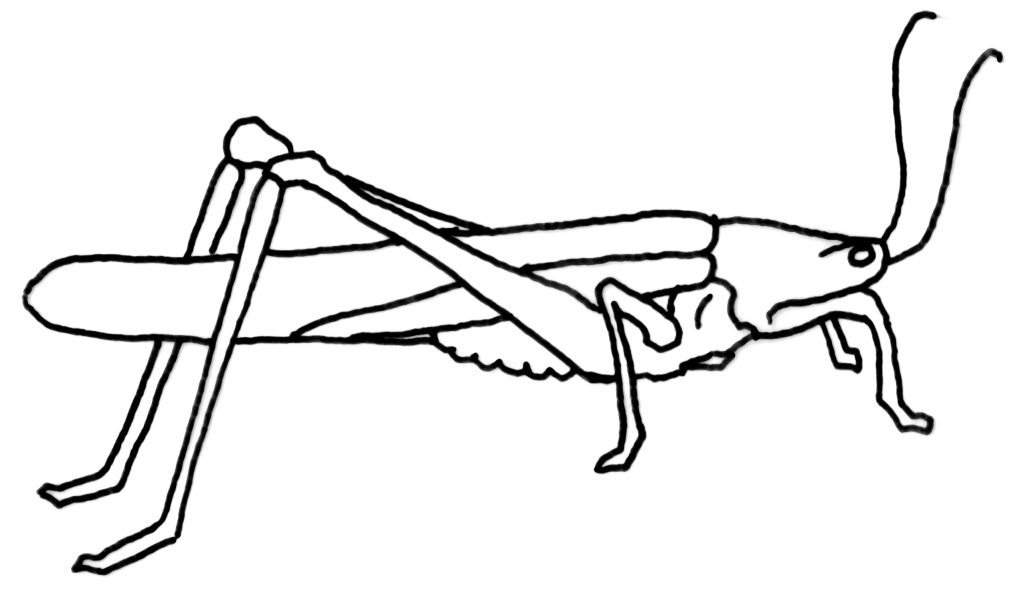

Next in the food chain, we find Common Coneheads (Neoconocephalus spp.). Coneheads are a type of grasshopper. Because they eat plants, we can call them herbivores. But in a food chain, we can also call them primary consumers — they eat (consume) plants, and they are first (primary) link in the food chain.

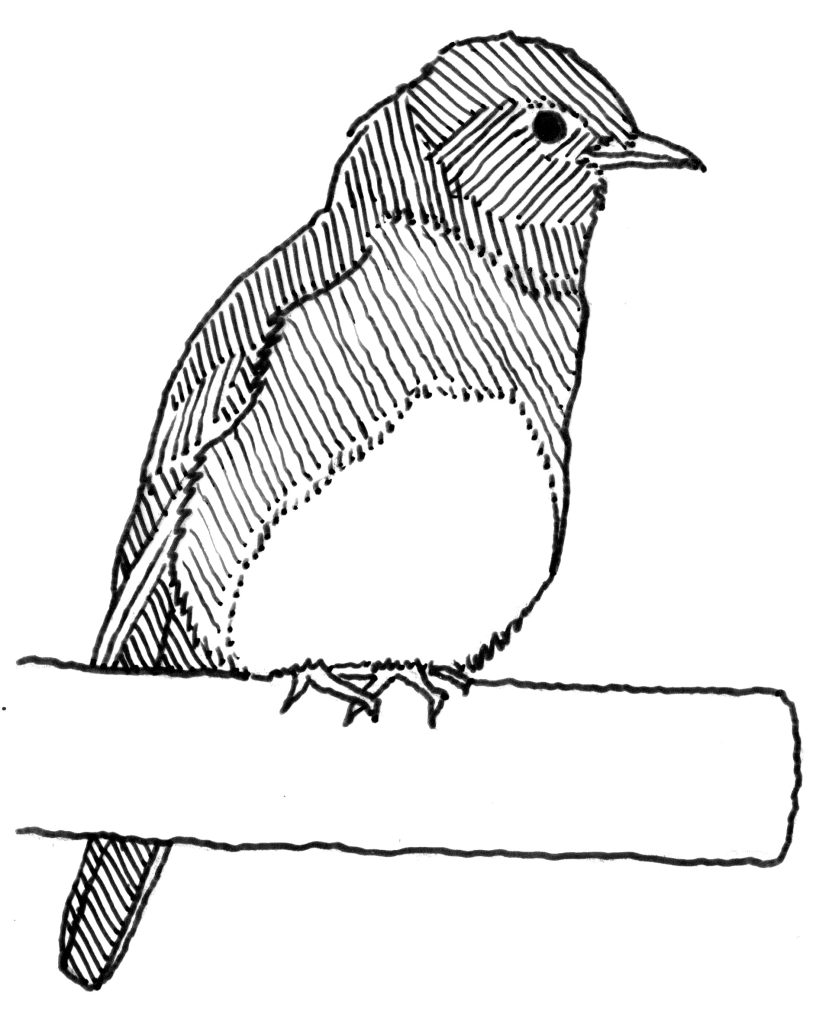

Next up the food chain are Eastern Bluebirds (Siala sialis), an attractive bird in the Thrush family. We can call these birds carnivores or predators because they eat other animals — in this case, the Coneheads. In a food chain, we call also them consumers.

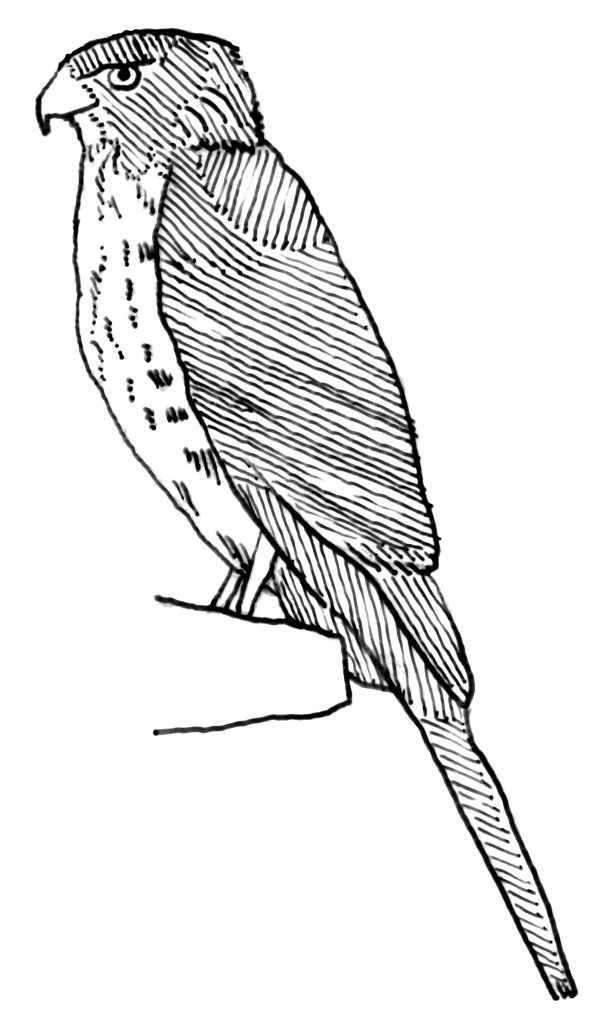

At the top of this food chain is the Cooper’s Hawk (Accipiter cooperii). This hawk mostly hunts other birds. Cooper’s Hawks are fond of eating all the birds in the Thrush family, including Bluebirds. As the top predator in this food chain, we can call them apex predators.

Energy comes from the Sun and moves up the food chain from producers to apex predator.

Set-up for the Food Chain Game

Set the boundaries. If you have a lot of players, you’ll need bigger boundaries. The area inside the boundaries is the Habitat.

The players divide up into Coneheads, Eastern Bluebirds, and Cooper’s Hawks. For each Hawk, you need about 3 Bluebirds. For each Bluebird, you need about 3 Coneheads. So if you have 13 players: 1 Hawk, 3 Bluebirds, 9 Coneheads. This game works best with lots of players.

Each organism gets a bag. Think of the bag as the creature’s stomach. It works best if you have small bags for the Coneheads, medium sized bags for Bluebirds, and big bags for Hawks.

One person is Mother Nature. Mother Nature scatters Grass Plants — which are small squares of felt — evenly across the Habitat. You’ll need at least 10 felt squares per player.

Game Play

After Mother Nature has spread the Grass Plants in the Habitat, she starts the first round.

First the Coneheads have about 10-20 seconds to hunt for Plants (allow more time for big Habitats). While Coneheads are finding food (picking up squares of felt and stuffing them in their bags), the Bluebirds and Hawks wait outside the Habitat.

After 10-20 seconds, Mother Nature tells the Bluebirds to begin hunting. Bluebirds catch their prey by tagging a Conehead and saying, “May I have your energy please?” The Conehead then kindly gives up their energy (i.e., their bag) — then the dead Conehead goes to the edge of the Habitat until the end of the round. All other Coneheads continue to gather food.

After another 10-20 seconds, Mother Nature tells the Hawks to begin hunting. Hawks catch their prey by tagging a Bluebird and saying, “May I have all your energy please?” The Bluebird kindly gives up all their energy (i.e., all the bags they have) — then the dead Bluebird goes to the edge of the Habitat until the end of the round.

Coneheads, Bluebirds, and Hawks continue hunting for food until Mother Nature ends the round. (Mother Nature should end the round before all the Coneheads and Bluebirds get eaten.)

Scoring

At the end of the round, each organism that hasn’t been eaten counts up its total Energy — the total number of felt squares in its bag (or stomach). Half of that Energy got expended in looking for food, and evading predators. The other half of that Energy is left over for reproduction (having children).

Coneheads need 4 total energy to have children and survive to the next round. With less than 4 total energy, they die.

Bluebirds need 8 total energy to have children and survive to the next round. With less than 8 total energy, they die.

Hawks need 16 total energy to have children and survive to the next round. With less than 16 total energy, they die.

Playing the Next Round

Mother Nature assigns all the organisms that have died to become Coneheads, Bluebirds, or Hawks, keeping the the same numbers as in the first round.

After you’ve played the last round, sit in a circle and talk about what it was like to role play each of the organisms. What did it feel like to be a Conehead? — an Eastern Bluebird? — a Cooper’s Hawk?

The Science Behind the Game

This game uses a simplified food chain to make it playable. Even so, the imaginary food chain in this game is based on facts. Let’s look at the facts, in order to find out how complicated real food chains are.

Coneheads do in fact eat mostly grasses, feeding mostly on the seeds. But they will also eat Sedges, a type of flowering plant that looks somewhat like grass.

Eastern Bluebirds do like to eat grasshoppers, but they eat eat many other kinds of insects as well — crickets, beetles, etc. According to one scientific study, grasshoppers only make up about 1.5% of their diet. Bluebirds also eat other small invertebrates, including earthworms, snails, millipedes, spiders, etc. Although about two thirds of their food consists of small animals, they also like to eat berries and other wild fruits. So they are not strict carnivores.

Cooper’s Hawks prefer to eat other birds. They are fond of eating birds in the Thrush family, which includes Eastern Bluebirds. But they will eat just about any bird they can catch. They will also hunt and eat small mammals, reptiles, and even insects.

One big problem with the Food Chain Game is with the numbers of organisms in the game. Bluebirds might eat a hundred insects in one day. A Cooper’s Hawk only eats about 2 birds a day. To make the game more like the real world, you really need hundreds of players who are Coneheads, dozens of players who are Bluebirds, and a couple of players as Cooper’s Hawks.

Another big problem with the Food Chain Game is that most animals eat a wide variety of foods. If you were really going to include all the foods Bluebirds eat, you’d have to add thousands of other players taking the roles of other insects and other invertebrates. And Cooper’s Hawks are known to eat more than 250 species of birds. That would mean even players taking the roles all those other birds, plus more players taking the roles of whatever all those other birds eat. You’d have to have hundreds of thousands of players — and maybe millions of felt squares, plus a field big enough for everyone.

At that point, you wouldn’t have a food chain any more. You’d have a food web — a huge interdependent web of life.

So you can see that in the real world, food chains are much more complicated than they are in the game.

Toxic Waste in the Food Chain

What happens when toxic waste gets into the food chain?

Rachel Carson found that the toxic chemical DDT got passed up the food chain. Think of our imaginary food chain. If a Conehead ate some grass seeds with DDT on them, the DDT would stay in its body. Then when a Bluebird ate the Conehead, the DDT would pass into the Bluebird and stay in its body. If the Bluebird ate dozens of insects with DDT in them, its body would accumulate quite a bit of DDT. Then if a Cooper’s Hawk at several Bluebirds, a lot of DDT would accumulate in its body. This is called bioaccumulation — more and more toxic chemicals accumulate in organisms the higher you go up the food chain.

You can try to model bioaccumulation in the Food Chain Game. Make a new rule that squares of a certain color are toxic waste — but none of the organisms knows which color until the round is over. If any organism has more than 4 toxic waste, they die of poisoning. Which organism is most vulnerable to toxic waste? (Or change the number of toxic waste to whatever works best for the size of your group.)

Notes: The Food Chain Game was inspired by similar games from Delta Education and Project WILD. For the diet of Eastern Bluebirds in the Food Chain game, see “Feeding of Nestling and Fledgling Bluebirds,” Benedict C. Pinowski, Wilson Bulletin 90-1, 1978. The diet of Cooper’s Hawks is variously reported, e.g., “Unfounded Assumptions about Diet of the Cooper’s Hawk,” John Bielefeldt, Robert N. Rosenfeld, and Joseph M. Papp (Condor 94:427-436, 1992) found a high percentage of mammals; “Hunting Behavior and Diet of Cooper’s Hawks: An Urban View,” Timothy C. Roth II and Steven L. Lima (Condor, 105:474-483, 2003) found urban birds such as starlings; the game models a commonly accepted view of A. cooperii diet that may not be based on actual research.

Blackbird Migration

From the Ecojustice Outdoors Book 5th ed., copyright (c) 2024 Dan Harper. All rights reserved.

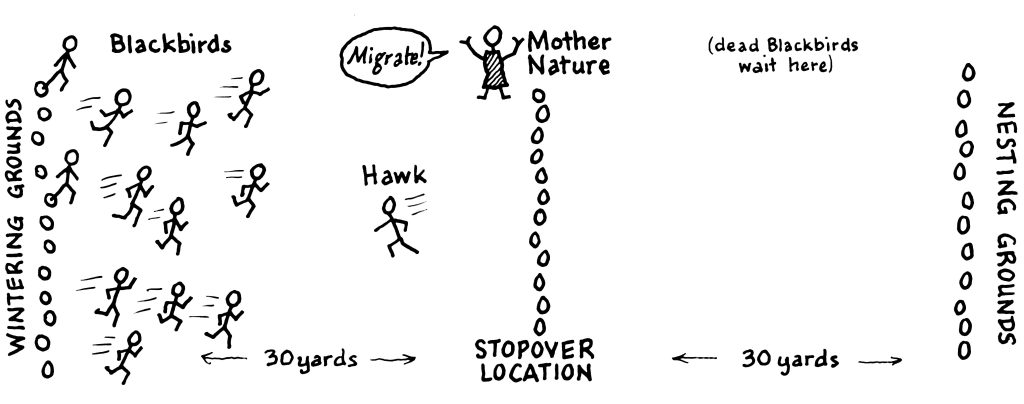

This is a game about how land use change can cause problems for migrating Red-winged Blackbirds. You’ll need at least 12 people to play the game.

Set up 3 lines of bases (use paper plates). The lines should be about 30 yards apart. To start, have one base for each player. Each base represents enough habitat to support one Red-winged Blackbird. One person is Mother Nature. All other players are Red-winged Blackbirds — except for a Cooper’s Hawk, who kills and eats Red-winged Blackbirds by tagging them. (Have 1 Cooper’s Hawk for every 12 Blackbirds.) All the Blackbirds begin at the wintering grounds. Each Blackbird must have one foot on a base to start. The Hawk must start far away from the Blackbirds.

I/ Migrating North

A/ Mother Nature shouts “Migrate!” The Blackbirds run from the wintering grounds to the stopover location. If the Hawk tags a Blackbird, the Blackbird dies and goes to the sidelines (they will come back later in the game). Blackbirds are safe from the Hawk once they are touching a base. No more than one Blackbird per base. When Mother Nature says “Stop!” Blackbirds and the Hawk must stop. Blackbirds who aren’t touching a base die and go to the sidelines (they will come back later in the game). Then Mother Nature rolls a 6-die to see how much habitat is lost to human development:

1 = lose 1 habitat at nesting grounds

2 = lose 2 habitats at nesting grounds

3 = lose 3 habitats at nesting grounds

4, 5, or 6 = nothing happens

B/ Mother Nature shouts “Migrate!” and the Blackbirds run on to the nesting grounds. Then Mother Nature rolls a 6-die to see how successful the breeding season was:

1 = 1 dead bird returns to the game

2 = 2 dead birds return to the game, etc.

(Dead birds return to the game in the order in which they died.)

II/ Migrating South

A/ Mother Nature shouts “Migrate!” and Blackbirds return to the stopover location. Follow the same rules as before. Then Mother Nature rolls a 6-die to see how much habitat is lost to human development:

1 = lose 1 habitat at both stopover and nesting grounds

2 = lose 2 habitats at both stopover and nesting grounds

3 = lose 3 habitats at both stopover and nesting grounds

4, 5, or 6 = nothing happens

B/ Mother Nature shouts “Migrate!” and birds return to the wintering grounds. Follow the same rules as before. Then Mother Nature rolls a 6-die to see how conservation laws restore habitat:

1 = gain 1 habitat at the nesting grounds

2 = gain 1 habitat at the stopover location

3 = gain 1 habitat each at both places

4, 5, or 6 = nothing happens

If Blackbird populations start going down, try stricter conservation laws. To do this, change the rule above so rolling a 4, 5, or 6 will also restore one habitat.

If Blackbird populations keep on declining, what other rules could you change to save the birds?

Notes: Blackbird Migration was inspired by the “Migration Headache” game in the Project WILD Aquatic K-12 Guide, Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (2002). Some of the science behind the game comes from Gordon R. Orians, Some Adaptations of Marsh-Nesting Blackbirds (Princeton Univ., 1980).

Moksha Patam (age 5 and up)

Moksha Patam is the classic board game from India upon which “Chutes and Ladders” is based. This game symbolizes the journey through life, and presents ideas of reincarnation, various virtues, etc.

Back in 2010, Sudha, a blogger living in Mumbai, wrote an excellent post on “Param Pada Sopanam,” another name for the same basic game, saying in part:

“Traditionally, Parama Pada Sopanam is played on the night of Vaikuntha Ekadashi (the 11th day after the new moon in the Tamil month of Margazhi). Many Hindus believe that the door to Vaikuntha, the abode of Lord Vishnu, will be wide open to welcome the devout and the faithful. Hindus also believe that dying on Vaikuntha Ekadashi will take them directly to the abode of Vishnu, liberating them from the cycle of rebirth. On this day, the devout stay up all night fasting and praying and playing the game helps them pass the time till dawn, when the fast is broken.”

For more cultural background on the game, read the entire post here.

Where to find Moksha Patam

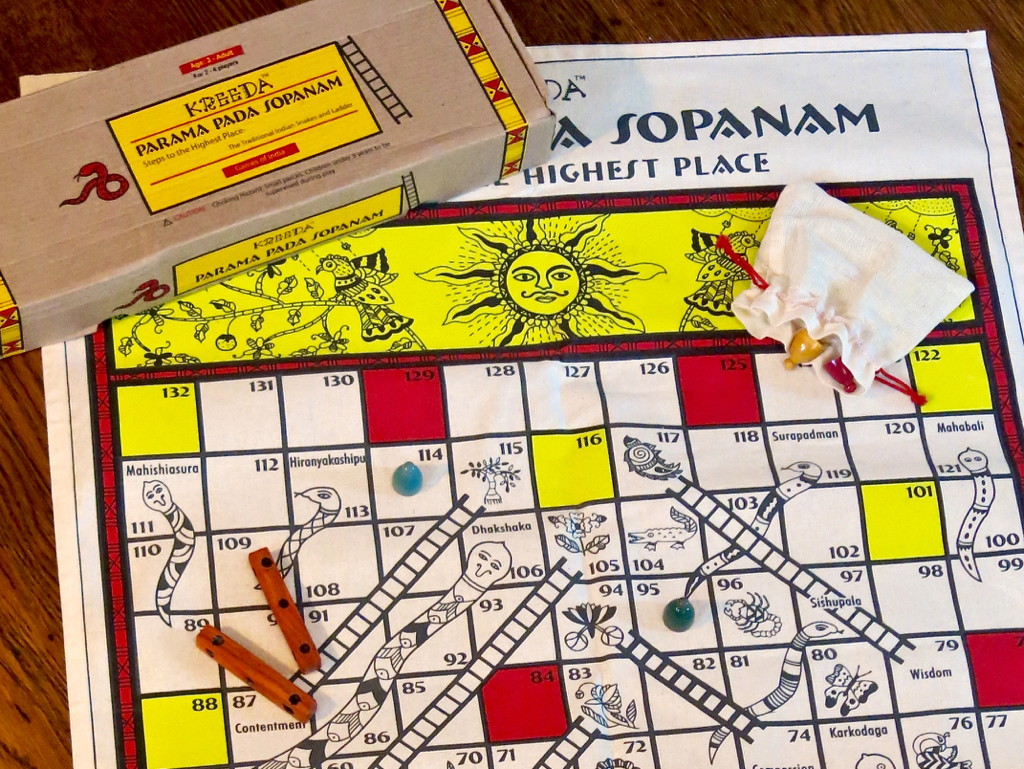

(1) In 2018, I was able to purchase a version of this game called “Param Pada Sopanum” form Kreeda, a games company based in India. International shipping charges cost more than the game, but the game itself was inexpensive; total cost was about $40. The quality was excellent, with a cloth game board, metal throwing sticks, and wood game pawns (see photo). The rules include brief stories described each of the mythological characters for which the snakes are named.

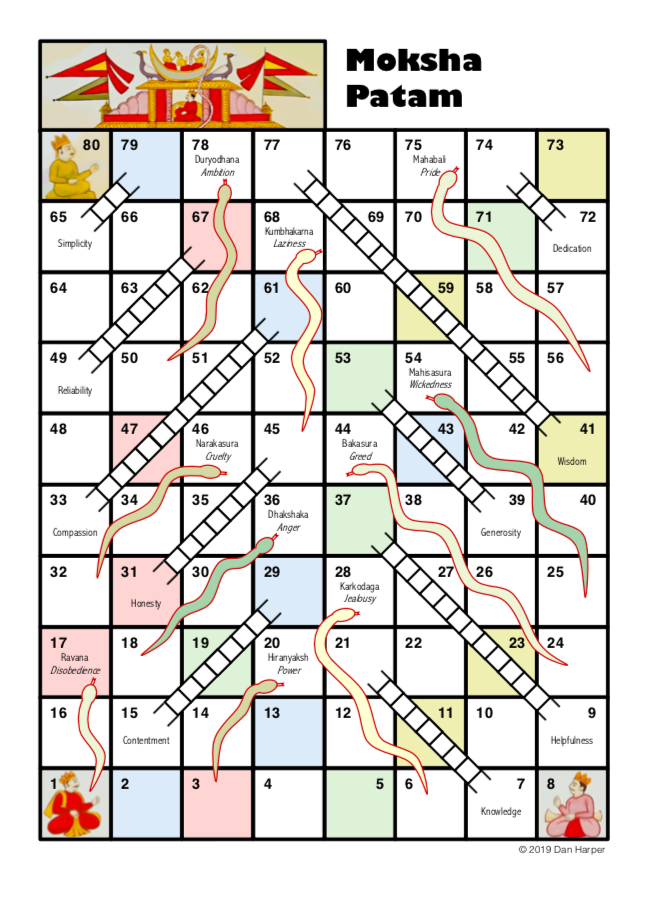

(2) Below is my small version of Moksha Patam game, designed to be played in a shorter time frame than the larger games, and which can be printed on 8-1/2 by 11 inch paper:

Moksha Patam game board and rules (PDF)

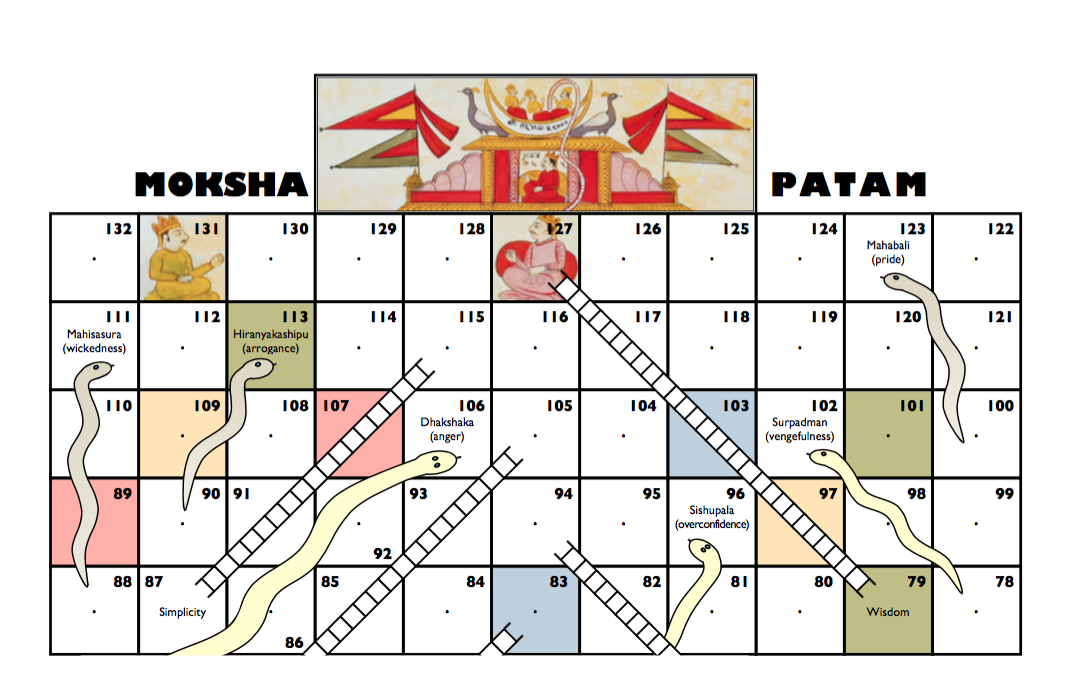

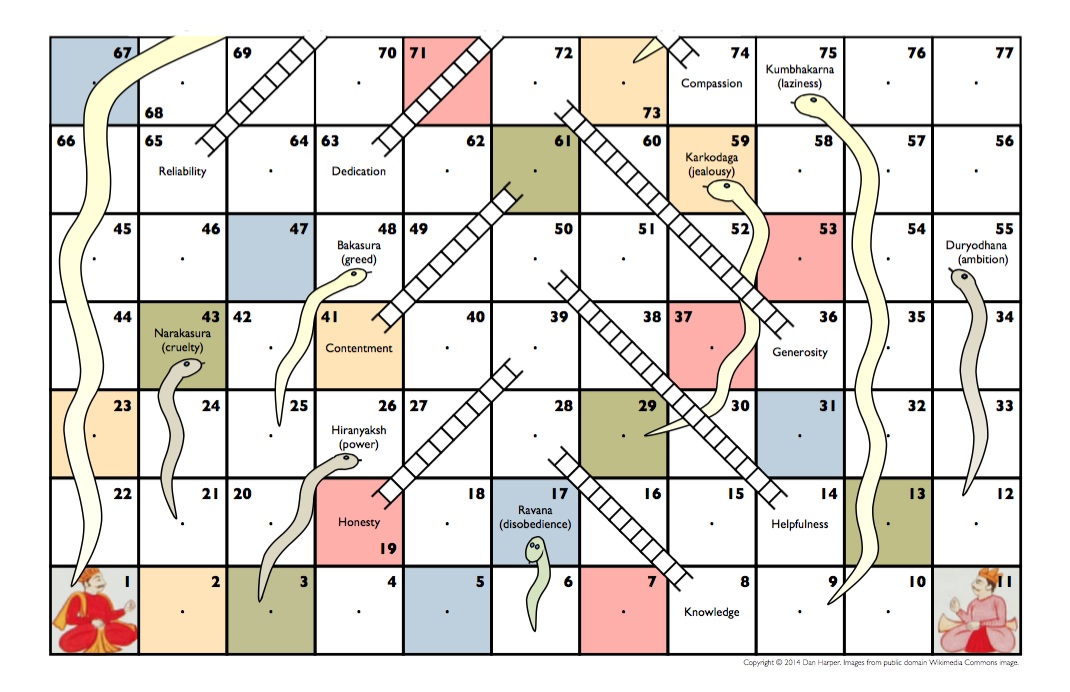

For a large (approx. 17 by 17 in.) version, print out these two PDF files, trim as needed, then tape them together to make a Moksha Patam game board. You will also need playing pieces and dice.

Moksha Patam rules

The goal of the game is to reach Nirvana, or Perfection — the highest place for a human being — which is shown at the top of the game board. This is a shorter version of the classic game, and is designed to be played in 15 to 20 minutes by 2 to 4 players (more players make the game last longer).

Equipment needed: In addition to the game board, you will need a standard 6-sided die and playing pieces. For playing pieces, you can use ordinary game pawns; but if you don’t have game pawns, coins (penny, nickel, dime, quarter) work well.

Rules:

1. The players take turns throwing the die, and moving the number of spaces shown.

2. If a player lands at the foot of a ladder, they climb to the top of the ladder and take another turn.

3. If a player lands at the head of a snake, they slide back down to the tail end. Each snake is named for an evil character in Hindu mythology — you can find short descriptions of some of these characters below.

4. If a player rolls a 1 or a 6, they then take another turn. If they roll a 1 or 6 and land on the head of a snake, they first slide to the tail of the snake, then take another turn. If they roll a 1 or 6 and land at the foot of a ladder, they first climb the ladder, then they take another turn (for having climbed the ladder), then still another turn (for having rolled a 1 or a 6).

5. Players must get to Perfection by exact count. For example, if you are on square 130 you must roll a 3 to get to Perfection; if you roll a 4, 5, or 6, you must stay on square 130; if you roll a 1 or 2, you may advance that number of squares.

6. The first player to reach Perfection wins.

The snakes:

Duryodhana, the leader of the Kauravas, hoped to win power away from the Pandavas, his cousins. But his ambition caused him to cheat and murder. He was at last defeated in battle.

Mahabali was a good king at first, but he was so proud he thought he was better than anyone else. Because of his pride, he wound up dying when a giant boy pushed his head into the underworld, causing him to drown.

Kumbhakarma was a rakshasa, or demon, who was a great warrior. When he asked the gods for even greater strength, they caused him to stammer and ask for sleep instead. He slept for six months.

Mahisasura was the wicked son of a rakshasa, or demon, who wanted to kill off the gods. He gained the power that no male being could kill him. But after fighting with the gods, the goddess Durga killed him.

Narakasura was was an evil king who was conquered all the kingdoms of earth, and he ruled with great cruelty. At last Krishna defeated Narakasura in battle. (Some say that the holiday of Diwali is a celebration of the defeat of Narakasura.)

Bakasura was a demon who demanded that the nearby village bring him a great deal of food each week — then he would eat all the food, and the person who brought it, too. Finally Bhima killed this demon.

Karkodaga was a magical serpent. When Damayanti chose to marry Nala, Saniswara was jeal-ous. He got Karkodaga to bite Nala, causing Nala to forget he was married. Fortunately, Damayanti helped Nala regain his memory.

Ravana was a king who wanted Sita, even though she was already married to Rama. He kid-napped Sita, and this disobedience led to a battle between Rama and Ravana. Ravana lost the battle and was killed.

Hiranyaksh was a powerful demon who came to believe he was more important than the gods and goddesses. He let his power go to his head, and attacked Mother Earth. The god Vishnu then had to kill him.