Greek Myths v. 1.0

A curriculum for upper elementary grades

Copyright notice:

Curriculum copyright (c) 2014 Dan Harper and Tessa Swartz

Lesson plans (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

Introduction copyright (c) 2015-2024 Dan Harper

Stories marked individually for copyright

Illustrations individually marked for copyright status

Back to the Table of Contents | On to Session Seven

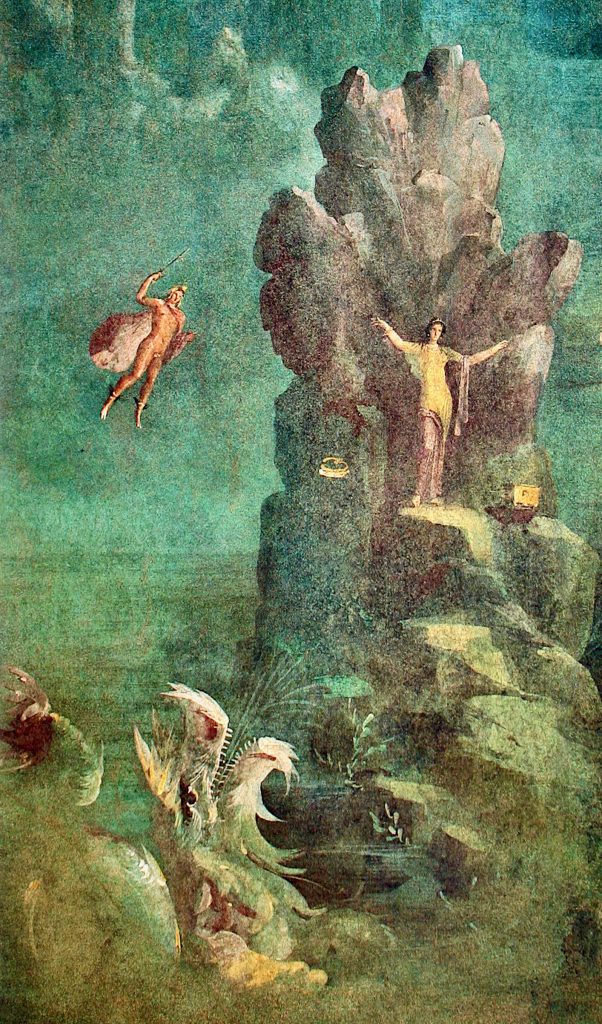

PERSEUS AND THE SEA MONSTER

We left Perseus hovering over the young woman who was chained to a rock….

This was the land of the Ethiopians, of which Cepheus was king. Cassiopeia his queen, proud of her beauty, had dared to compare herself and her daughter to the Sea-Nymphs, which roused their indignation to such a degree that they sent a prodigious sea-monster to ravage the coast. To appease the deities, Cepheus was directed by the oracle to chain his daughter Andromeda near the edge of the sea, to be devoured by the monster. This was the young woman over which Perseus hovered.

As he hovered over her he said, “O young woman, undeserving of those chains, but rather of such as bind fond lovers together, tell me, I beg you, your name, and the name of your country, and why you are thus bound.”

At first she was silent, and refused to speak to him. But when he repeated his questions, for fear she might be thought guilty of some fault which she dared not tell, she finally told Perseus her name and that of her country, and her mother’s pride in her own beauty, and in her daughter’s beauty.

Before she had done speaking, a sound was heard off upon the water, and the sea-monster appeared, with his head raised above the surface, cutting through the waves with his broad breast. The young woman’s eyes grew wider, she started in surprise, and pulled away from the monster to the extent her chains would allow. The father and mother who had now arrived at the scene, both of them feeling wretched, but the mother more justly so, stood by, not able to afford protection, but only to pour forth lamentations and to embrace the victim.

Then spoke Perseus: “There will be time enough for tears; this hour is all we have for rescue. My rank as the son of Zeus and my renown as the slayer of Medusa might make me acceptable as a suitor. But I will try to win her by saving her from the sea monster, if the gods will only be in favor of my success. If she be rescued by my valor, I demand that she be my reward.”

The parents consented (how could they hesitate?) and promised a royal dowry with her.

And now the monster was within the range of a stone thrown by a skilful slinger, when with a sudden bound the youth soared into the air. As an eagle, when from his lofty flight he sees a serpent basking in the sun, pounces upon it and seizes it by the neck to prevent it from turning its head round and using its fangs, so the youth darted down upon the back of the monster and plunged his sword into its shoulder. Irritated by the wound, the monster raised itself in the air, then plunged into the depths; then, like a wild boar surrounded, by a pack of barking dogs, turned swiftly from side to side, while the youth eluded its attacks by means of his wings.

Wherever he can find a passage for his sword between the scales he makes a wound, piercing now the side, now the flank, as it slopes towards the tail. The brute spouts from its nostrils water mixed with blood. The wings of the hero are wet with it, and he dares no longer trust to them. Alighting on a rock which rose above the waves, and holding on by a projecting fragment, as the monster floated near he gave it a death stroke. The people who had gathered on the shore shouted so that the hills re-echoed the sound. No one knows what the monster thought as it died; it had only done what the Sea Nymphs had asked of it, and had died as a result.

The parents, transported with joy, embraced their future son-in-law, calling him their deliverer and the savior of their house. Andromeda was released from her chains, and descended from the rock to look at Perseus, the man to whom she was now promised in marriage by her thoughtless parents.

Cassiopeia is called “the starred Ethiopean queen” because after her death she was placed among the stars, forming the constellation of that name. Though she attained this honor, yet the Sea-Nymphs, her old enemies, prevailed so far as to cause her to be placed in that part of the heaven near the pole, where every night she is half the time held with her head downward, to give her a lesson of humility.

The joyful parents, with Perseus and Andromeda, repaired to the palace, where a banquet was spread for them, and all was joy and festivity. But suddenly a noise was heard of warlike clamor, and Phineus, who was both the uncle of, and the promised husband of the young woman, burst in with a party of his adherents, demanding his right to marry Andromeda. It was in vain that Cepheus remonstrated — “You should have claimed her when she lay bound to the rock, the monster’s victim. The sentence of the gods dooming her to such a fate dissolved all engagements, as death itself would have done.”

Phineus made no reply, but hurled his javelin at Perseus, but it missed its mark and fell harmless. Perseus would have thrown his in turn, but the cowardly assailant ran and took shelter behind the altar. But his act was a signal for an onset by his band upon the guests of Cepheus. They defended themselves and a general conflict ensued, the old king retreating from the scene after fruitless expostulations, calling the gods to witness that he was guiltless of this outrage on the rights of hospitality.

Perseus and his friends maintained for some time the unequal contest; but the numbers of the assailants were too great for them, and destruction seemed inevitable, when a sudden thought struck Perseus: “I will make my enemy defend me.” Then with a loud voice he exclaimed, “If I have any friend here let him turn away his eyes!” and held aloft Medusa’s head.

“Seek not to frighten us with your jugglery,” said Thescelus, and raised his javelin in act to throw, and became stone in the very attitude. Ampyx was about to plunge his sword into the body of a prostrate foe, but his arm stiffened and he could neither thrust forward nor withdraw it. Another, in the midst of a vociferous challenge, stopped, his mouth open, but no sound issuing. One of Perseus’s friends, Aconteus, caught sight of Medusa’s head, and stiffened like the rest. Astyages struck him with his sword, but instead of wounding, it recoiled with a ringing noise.

Phineus beheld this dreadful result of his unjust aggression, and felt confounded. He called aloud to his friends, but got no answer; he touched them and found them stone. Falling on his knees and stretching out his hands to Perseus, but turning his head away he begged for mercy.

“Take all,” said he, “give me but my life.”

“Base coward,” said Perseus, “thus much I will grant you; no weapon shall touch you; moreover, you shall be preserved in my house as a memorial of these events.”

So saying, he held the Medusa’s head to the side where Phineus was looking, and in the very form in which he knelt, with his hands outstretched and face averted, he became fixed immovably, a mass of stone.

Andromeda finally did marry Perseus, and left her parents to live with him in Tiryns, in the land of Argos. Perhaps she was glad enough to get away from such thoughtless parents. She and Perseus had nine children together: two daughters, Autochthe and Gorgophone; as well as seven sons: Perses, Alcaeus, Heleus, Mestor, Sthenelus, Electryon, and Cynurus. After she died, the gods and goddesses placed her in the heavens as the constellation Andromeda. The constellation shows her chained to the rock, and some see a constellation of a fish at her feet; no doubt she would prefer to be remembered in some other way, but like it or not she will always be remembered for the most dramatic moment in her life.

Source: We adapted this story from Bulfinch’s mythology: The age of fable, The age of chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne, rev. ed., by Thomas Bulfinch (New York: T. Y. Crowell Co., 1913), chapter XV, “The Graeae and Gorgons — Perseus and Medusa — Atlas — Andromeda.” Public domain story.

Pronunciation guide:

Phineus — FIN ee us

Thescelus — THEH sell us

Ampyx — AM pix

Aconteus — ah KON tee us

Astyages — ah stee AH gis

UNIT TWO: MONSTERS

Session 6: Perseus, pt. 2

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story “Perseus and the Sea Monster.”

Read the story above.

III/ Act out the story.

(Before acting out the story, you might want to look back at the last lesson, and recall that Perseus is a bully, and remind the children of how Perseus would walk — with a swagger. See previous lesson for more on this.)

Act out the whole story just as it has been done in previous classes.

Ask the children who are the characters in the story, and perhaps have someone (you or one of the children) write them down. Ask who wants to act out the different parts (and note that you don’t have to be the same gender as the part you’d like to act out).

Now act out the story. Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with you; you will sit facing the stage.

B. After acting the story out, have everyone sit in a circle. Say something like this: “Although Perseus is the hero of the story, he doesn’t act very heroic. A real hero, seeing someone in danger, would help them without thought of reward. But Perseus, before he will fight the sea monster, demands that Andromeda be given to him in marriage. We Unitarian Universalists believe that no one should be forced into a marriage they don’t want, so we feel that Perseus is not a nice person!”

III/ Act out the story differently.

Now act out the story about Perseus and Andromeda again. But this time, have Perseus kill the sea monster as soon as Andromeda is threatened — do not have Perseus bargain for marriage. Here’s how you can start the story:

Perseus was hovering over a young woman who was chained to a rock.

This was the land of the Ethiopians, of which Cepheus was king. Cassiopeia his queen, proud of her beauty, had dared to compare herself and her daughter to the Sea-Nymphs, which roused their indignation to such a degree that they sent a prodigious sea-monster to ravage the coast. To appease the deities, Cepheus was directed by the oracle to chain his daughter Andromeda near the edge of the sea, to be devoured by the monster. This was the young woman over which Perseus hovered.

As he hovered, he said, “O young woman, this doesn’t seem at all right. Please tell me why you are bound here.” At first she was silent, and refused to speak to him. But when he repeated his questions, for fear she might be thought guilty of some fault which she dared not tell, she finally told Perseus her name and that of her country, and her mother’s pride in her own beauty, and in her daughter’s beauty. She had been bound here to answer for her mother’s pride!

Before she had done speaking, a sound was heard off upon the water, and the sea-monster appeared, with his head raised above the surface, cutting through the waves with his broad breast. The young woman’s eyes grew wider, she started in surprise, and pulled away from the monster to the extent her chains would allow. The father and mother who had now arrived at the scene, both of them feeling wretched, but the mother more justly so, stood by, not able to afford protection, but only to pour forth lamentations and to embrace the victim.

Perseus did not speak. And now the monster was within the range of a stone thrown by a skilful slinger, when with a sudden bound the youth soared into the air. As an eagle, when from his lofty flight he sees a serpent basking in the sun, pounces upon it and seizes it by the neck to prevent it from turning its head round and using its fangs, so the youth darted down upon the back of the monster and plunged his sword into its shoulder. Irritated by the wound, the monster raised itself in the air, then plunged into the depths; then, like a wild boar surrounded, by a pack of barking dogs, turned swiftly from side to side, while the youth eluded its attacks by means of his wings.

Wherever he can find a passage for his sword between the scales he makes a wound, piercing now the side, now the flank, as it slopes towards the tail. The brute spouts from its nostrils water mixed with blood. The wings of the hero are wet with it, and he dares no longer trust to them. Alighting on a rock which rose above the waves, and holding on by a projecting fragment, as the monster floated near he gave it a death stroke. The people who had gathered on the shore shouted so that the hills re-echoed the sound. No one knows what the monster thought as it died; it had only done what the Sea Nymphs had asked of it, and had died as a result.

The parents, transported with joy, thanked the young man for saving their daughter. “What can we do for you?” they cried.

“I ask nothing of you,” said the hero, “other than that I be allowed to stay in your palace for a few days and recover from my fight with the monster.”

The parents gladly welcomed him to stay. The joyful parents, with Perseus and Andromeda, repaired to the palace, where a banquet was spread for them, and all was joy and festivity.

But suddenly a noise was heard of warlike clamor, and Phineus, who was both the uncle of, and the promised husband of the young woman, burst in with a party of his adherents, demanding his right to marry Andromeda.

Cepheus remonstrated with him: “You should have claimed her when she lay bound to the rock, the monster’s victim. The sentence of the gods dooming her to such a fate dissolved all engagements, as death itself would have done. Instead, you ran away, leaving this stranger to come and save her by killing the monster.”

Phineus made no reply, but picked up his javelin at Perseus….

Act out this revised story, and then move immediately to the next activity….

IV/ Think-pair-share: discussing the story

Ask:

(1) What should Perseus do now? Be ready to explain your answer!

Ask the children to THINK for a few moments (maybe ten seconds at most) about how they would answer this question.

Now quickly PAIR up the children with the person next to them (if you have an odd number, there will be a group of three). Tell them to talk about their answers with their partners for a few moments (maybe fifteen to thirty seconds).

Now ask everyone to SHARE their own answer with the whole group. Repeat the question, and go around the circle, asking each child to give their answer.

(If you need to review how Think-Pair-Share works, a good summary of think-pair-share can be found at the following Web site — “ReadingQuest Strategies for Reading Comprehension: Think-Pair-Share.”)

V/ Conversation and optional snack

Think-pair-share is a great way to help every child participate in a structured conversation. If you have time, you may wish to extend the conversation in a less formal manner. Here is something to talk about:

Whoever owns the head of Medusa has a great deal of power. They can kill anyone they want, just by having that person look on the head of Medusa — in fact, they can kills dozens or even hundreds of people at once using the head of Medusa!

So do you think the goddess Athena should have allowed Perseus to own the head of Medusa? Why or why not? And do you think Perseus used the head wisely? Why or why not?

And here’s another question:

— Andromeda doesn’t have many good choices in this story. She can either marry Perseus, who is a killer but also a bully and not very heroic, or she can marry Phineus, who is her uncle (yuck!) and not very nice. Worse yet, her mother brags too much, and who has to pay for it? — Andromeda does, not her mother!

So here’s a final question: if you were Andromeda, what would you do?

VI/ Free play

If you need to fill more time, you could play a game of some kind. Just make sure you have everyone come together for a closing circle before you’re done.

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about Perseus, right? What happened in the story? What was Andromeda thinking and feeling?” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

End by saying together some closing words, something like these:

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

Then before you all go, tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (assuming that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.