Greek Myths v. 1.0

A curriculum for upper elementary grades

Copyright notice:

Curriculum copyright (c) 2014 Dan Harper and Tessa Swartz

Lesson plans (c) 2014-2024 Dan Harper

Introduction copyright (c) 2015-2024 Dan Harper

Stories marked individually for copyright

Illustrations individually marked for copyright status

Back to the Table of Contents | On to Session Six

PERSEUS AND MEDUSA

Perseus was the son of the god Zeus and the human Danae. Perseus’ grandfather Acrisius, alarmed by an oracle which had told him that his daughter’s child would be the instrument of his death, locked Danae in an underground room made out of bronze. This did not stop Zeus, who turned himself into a golden rain shower, and so entered the underground chamber where Danae was kept.

Soon Danae was pregnant, and gave birth to Perseus. Acrisius, still worried about the oracle, caused the mother and child to be shut up in a chest and set adrift on the sea. The chest floated towards Seriphus, where it was found by a fisherman who conveyed the mother and infant to Polydectes, the king of the country, by whom they were treated with kindness.

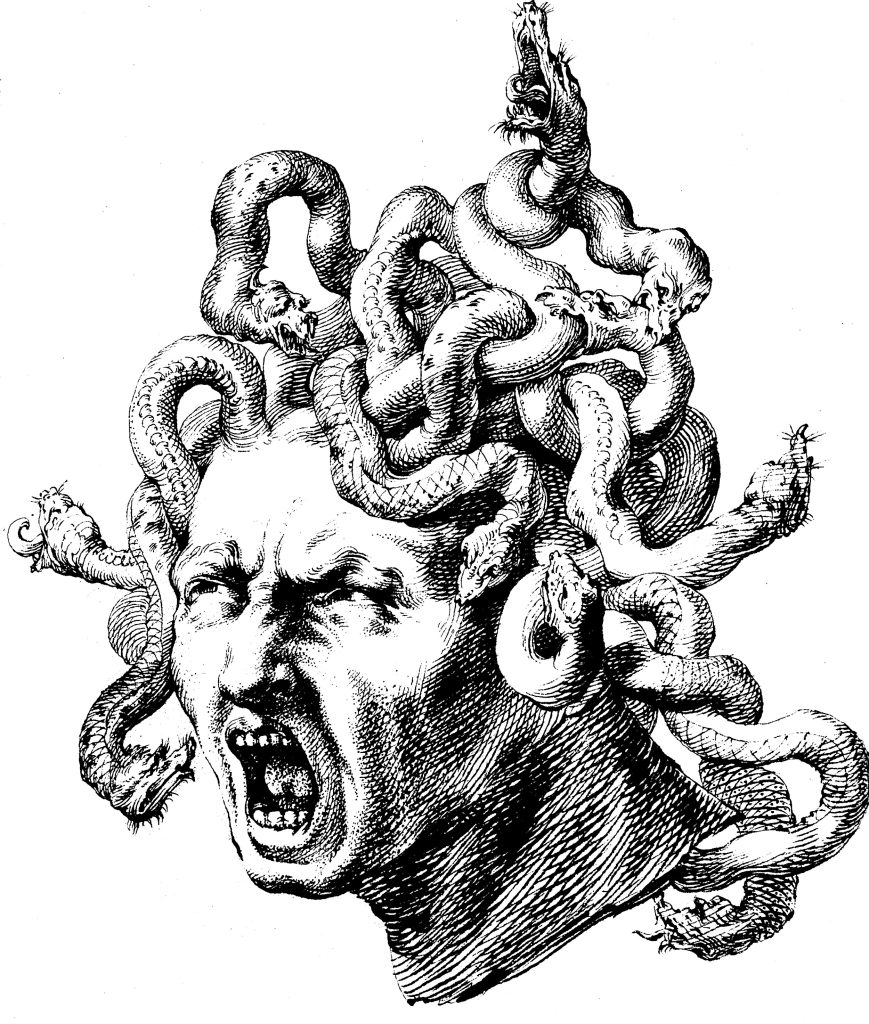

When Perseus was grown up Polydectes, king of the island of Seriphos, sent him to attempt the conquest of Medusa, a terrible monster who had laid waste the country. She was once a beautiful maiden whose hair was her chief glory, but as she dared to vie in beauty with Athena, the goddess deprived her of her charms and changed her beautiful ringlets into hissing serpents. She became a cruel monster of so frightful an aspect that no living thing could behold her without being turned into stone. All around the cavern where she dwelt might be seen the stony figures of men and animals which had chanced to catch a glimpse of her and had been petrified with the sight. Perseus, favored by Athena and Hermes, the former of whom lent him her shield and the latter his winged shoes, approached Medusa while she slept, and taking care not to look directly at her, but guided by her image reflected in the bright shield which he bore, he cut off her head and gave it to Athena, who fixed it in the middle of her Aegis, or shield.

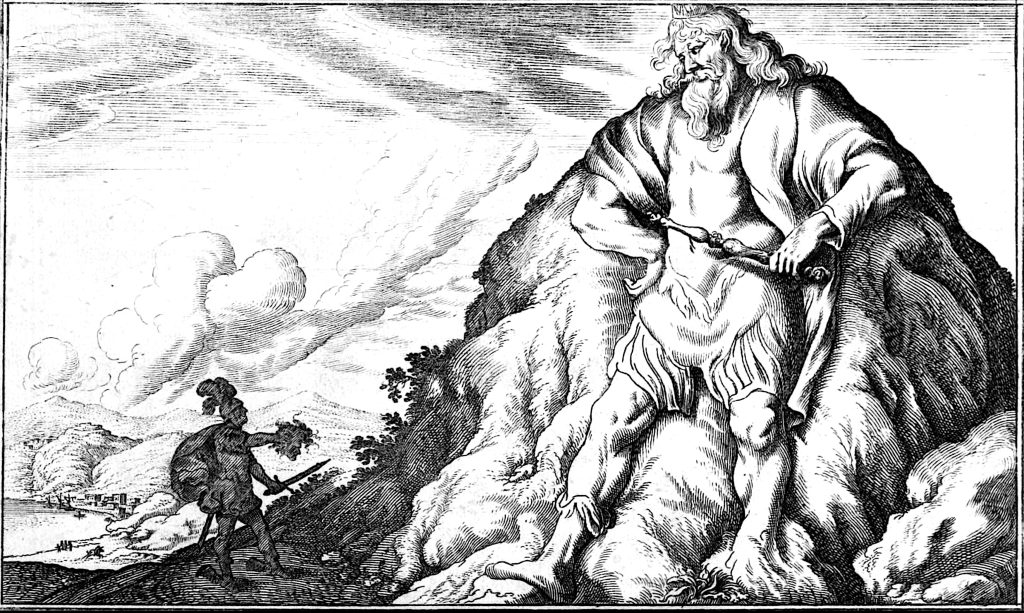

After the slaughter of Medusa, Perseus, bearing with him the head of the Gorgon, flew far and wide, over land and sea. (Presumably Athena let him use the head for a time, but the old myths do not tell us this.) As night came on, he reached the western limit of the earth, where the sun goes down. Here he would gladly have rested till morning. It was the realm of the Atlas, a huge Titan. He was rich in flocks and herds and had no neighbor or rival to dispute his state. But his chief pride was in his gardens, whose fruit was of gold, hanging from golden branches, half hid with golden leaves.

Perseus said to him, “I come as a guest. If you honor those who are descended from the gods and goddesses, I claim Zeus for my father. If you honor mighty deeds, I claim the conquest of the Gorgon. I seek rest and food.”

But Atlas remembered that an ancient prophecy had warned him that a son of Zeus should one day rob him of his golden apples. So he answered, “Begone! Neither your false claims of glory nor parentage shall protect you!” And he attempted to thrust him out.

Perseus, finding the giant too strong for him, said, “Since you value my friendship so little, deign to accept a present.” And turning his face away, he held up the Gorgon’s head. Atlas, with all his bulk, was changed into stone. His beard and hair became forests, his arms and shoulders cliffs, his head a summit, and his bones rocks. Each part increased in bulk till he became a mountain, and (such was the pleasure of the gods and goddesses) heaven with all its stars rests upon his shoulders.

Perseus, continuing his flight, arrived at the country of the Ethiopians, of which Cepheus was king. Cassiopeia his queen, proud of her beauty, had dared to compare herself and her daughter to the Sea-Nymphs, which roused their indignation to such a degree that they sent a prodigious sea-monster to ravage the coast. To appease the deities, Cepheus was directed by the oracle to chain his daughter Andromeda near the edge of the sea, to be devoured by the monster.

As Perseus looked down from his aerial height he beheld the young woman chained to a rock, and waiting the approach of the serpent. She was so pale and motionless that if it had not been for her flowing tears and her hair that moved in the breeze, he would have taken her for a marble statue. He was so startled at the sight that he almost forgot to wave his wings.

As he hovered over her he said, “O young woman, undeserving of those chains, but rather of such as bind fond lovers together, tell me, I beseech you, your name, and the name of your country, and why you are thus bound.”

The woman was silent for a long while before she began to speak….

To Be Continued.

Source: Story adapted from Bulfinch’s mythology: The age of fable, The age of chivalry, Legends of Charlemagne, rev. ed., by Thomas Bulfinch (New York: T. Y. Crowell Co., 1913), chapter XV, “The Graeae and Gorgons — Perseus and Medusa — Atlas — Andromeda.” Public domain story.

Pronunciation guide:

Perseus — PER see us

Danae — DAH nay ee

Acrisius — ah KRIS ee us

Seriphus — se RI fuss

Polydectes — poll i DECK tess

Cepheus — SI fee us

Cassiopeia — kass ee o PEE ah

Andromeda — an DROM eh duh

UNIT TWO: MONSTERS

Session Five: Perseus, pt. 1

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story “Perseus and Medusa”

Read the story above.

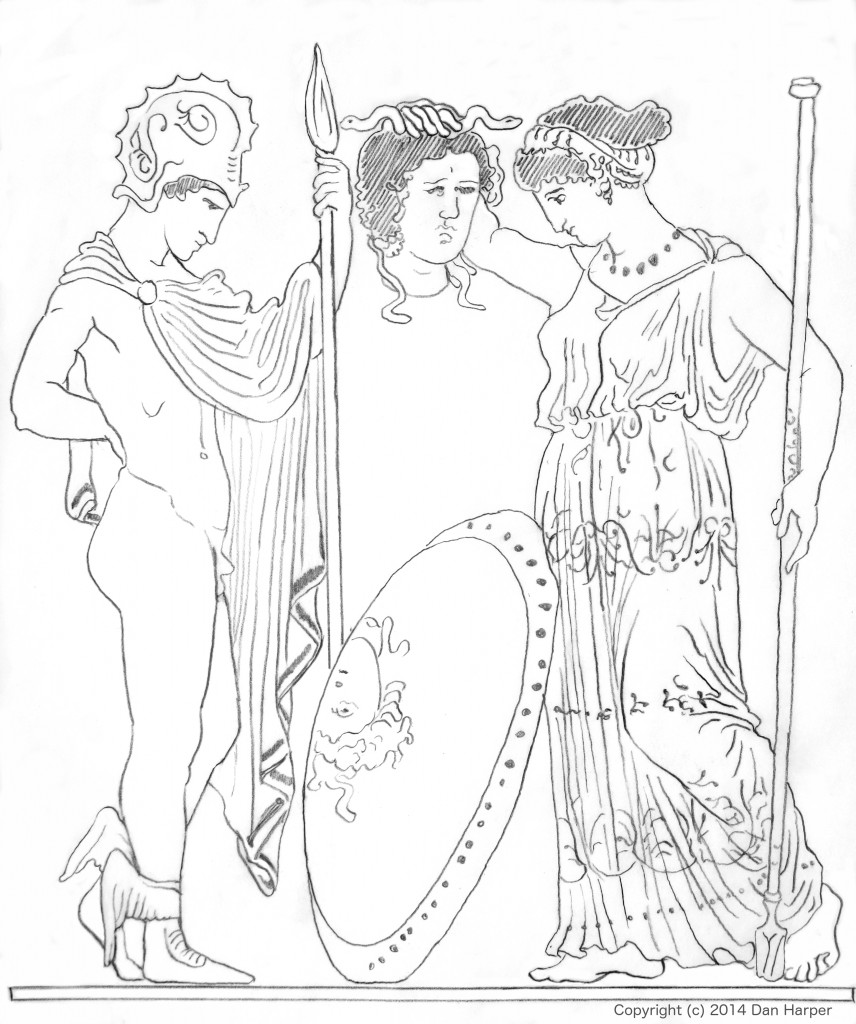

You can print the image below and use it as a coloring page.

III/ Act out the story

To act out this story, it helps to think together about how the characters might appear. For Medusa, we’ll ask: What does the emotion of rage look like? For Perseus, we’ll ask: What does swaggering look like?

A. Preparing to act out the story: Medusa

Say something like this to the children:

“Let’s talk for a moment about Medusa. What did Medusa’s face look like? Tell the children that many people over the centuries have felt that Medusa’s face showed an expression of rage. (As an example, you can show them the painting of Medusa by Caravaggio, below). When you’re really angry — when you’re full of rage — what does your face look like?”

Emily Erwin Culpepper, a scholar of religion, describes what rage looks like as follows: “My face is bursting, contorting with terrible teeth, flaming breath, erupting into ridges and contours of rage, hair hissing.” If you wish, you can share this description with the children.

Now ask the children to express rage with their own faces. Then you can ask them this question: Do rage-filled faces look frightening?

B. Preparing to act out the story: Perseus

Say something like this to the children:

“After talking about Medusa, let’s talk about Perseus. Although Perseus is the hero of the story, he doesn’t act very heroic. First of all, although he does kill Medusa, really the goddess Athena tells him how to do it. And when he gets into a fight with Atlas, and starts losing, he cheats — he whips out the head of Medusa and turns Atlas to stone. In fact, Perseus comes across as a kind of bully — someone who gets his own way by relying on stronger friends to help him, and by cheating.

“People who are like this tend to walk in a certain kind of way. They tend to swagger when they walk, and they try to look tough and brave — though really, they are not tough, and they are not brave.”

Ask the children to walk like this — with a little bit of a swagger, trying to look tough.

C. Act out the story

Next, act out the whole story just as it has been done in previous classes.

Ask the children who are the characters in the story, and perhaps have someone (you or one of the children) write them down. Ask who wants to act out the different parts (and note that you don’t have to be the same gender as the part you’d like to act out). One child can be the head of Medusa, and have a rage-filled face. One child can be Perseus, and swagger and try to look tough.

Now act out the story. Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with you; you will sit facing the stage.

III/ Think-pair-share: discussing the story

Get everyone back into a circle. Remind them that in the story, the goddess Athena decides to turn Medusa into a monster just because Medusa is prettier than the goddess. So here’s one question:

(1) Instead of turning Medusa into a monster, what’s a better option for Athena? Be ready to explain your answer!

Ask the children to THINK for a few moments (maybe ten seconds at most) about how they would answer this question.

Now quickly PAIR up the children with the person next to them (if you have an odd number, there will be a group of three). Tell them to talk about their answers with their partners for a few moments (maybe fifteen to thirty seconds).

Now ask everyone to SHARE their own answer with the whole group. Repeat the question, and go around the circle, asking each child to give their answer.

(If you need to review how Think-Pair-Share works, a good summary of think-pair-share can be found at the following Web site — “ReadingQuest Strategies for Reading Comprehension: Think-Pair-Share.”)

If you have time, here’s another question to ask:

(2) The story tells us a lot about what Perseus is thinking and feeling, but what do you think Medusa was thinking and feeling?

Again: Ask the children to THINK for a few moments (maybe ten seconds at most) about how they would answer this question.

Now quickly PAIR up the children with the person next to them (if you have an odd number, there will be a group of three). Tell them to talk about their answers with their partners for a few moments (maybe fifteen to thirty seconds).

Now ask everyone to SHARE their own answer with the whole group. Repeat the question, and go around the circle, asking each child to give their answer.

IV/ Conversation and optional snack

Think-pair-share is a great way to help every child participate in a structured conversation. If you have time, you may wish to extend the conversation in a less formal manner. Here is something to talk about:

An ancient Greek writer names Pelaephatus did not believe in magic or supernatural explanations. So he came up for his own explanation of the story of Perseus, which goes like this:

Perseus cut Medusa up into pieces, and took the head and nailed it to the prow of his trireme (his ship), which he named after Medusa. Then he sailed from one island to the next, demanding money from the islanders and killing those who refused to pay him. One day he sailed to the island of Seriphus, and ordered the people who lived there to give him money. The people of Seriphus asked him to give them a few days so they could get the money together. Perseus went away (perhaps to go harrass another island), and while he was away the people of Seriphus set up human-sized stones in their town, and then sneaked off the island. When Perseus returned to get his money, he found that all the people had gone. In their places were stones this size of human beings, and so he believed that the people had been turned into stone. From then on, whenever he invaded another island to extort money, he would tell the people: You better watch out and give me the money, or Medusa’s head will turn you all to stone, just as her head turned all the people of Seriphus into stone.”

— What do you think of this story? Does this sound any more believable than the original story?

— And what do you think — do we need to come up with rational explanations of myths? Or are myths nothing more than enjoyable fiction? Or do you think there is another kind of meaning in the myths — they’re not literally true, but there is some kind of truth in them?

If you decided to have a snack, you can have one of the children pass out snack while you start this conversation.

VI/ Free play

If you need to fill more time, you could play a game of some kind. Just make sure you have everyone come together for a closing circle before you’re done.

VII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle. Rather than hold hands, try having the children gently touch toes with their neighbors on either side.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about Perseus and Medusa, right? What happened in the story? What was Medusa thinking and feeling?” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

End by saying together some closing words, perhaps something like these:

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.

Then before you all go, tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (assuming that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

LEADER RESOURCE: Understanding Medusa

When we chose stories for this course, we placed the Medusa story at the top of our lists. What makes Medusa such a fascinating figure? The face of Medusa contains great power: the power to freeze others into stone. So the story of Medusa can lead to interesting explorations of power, and the use of power.

But who was Medusa, really? Contemporary thinkers have come up with some interesting answers.

A. A factual origin?

The poet Robert Graves felt that there was a factual origin to the stories about Medusa. Originally, Graves said, the face of Medusa had a religious purpose: it was “an ugly mask assumed by the priestesses on ceremonial occasions to frighten away trespassers; at the same time they made hissing noises, which accounts for Medusa’s snake locks. There never was a real Gorgon; there was only a prophylactic ugly face formalized into a mask.”

Thus in Graves’s view, Medusa is not evil; rather Medusa originated as a means to maintain the sanctity of religious rituals. (1)

B. A positive image?

In 1986 Emily Erwin Culpepper claimed Medusa’s face as a positive image for women. Culpepper once fought of a would-be rapist, and later she realized that her rage-contorted face helped her fight: “As I felt my face twist again into the fighting frenzy, I turned to the mirror and looked. What I saw in the mirror is a Gorgon, a Medusa, if ever there was one. This face was my own and yet I knew I had seen it before and I knew the name to utter. ‘Gorgon! Gorgon!’ reverberated in my mind. I knew then why the attacker had become so suddenly petrified. And knew with a great shuddering relief that I would win the fight against self-blame….” (2)

Thus in Culpepper’s view, Medusa’s image can serve as a way to achieve a better self-image.

C. A racial interpretation?

Playwright Dorothea Smartt feels the stories about Medusa may have originated in encounters between ancient Greeks who were white, and Africans who were black: “I thought to myself: Medusa was probably some black woman with nappy hair, and some white man saw her and cried: a monster!, and feared her, and so told stories about her dangerous potential. To see her more clearly, I studied anthropology and thought about the first encounters of white men in Africa, and how they might have viewed and feared these strange and fantastic creatures: black women. What did early explorers see or think they saw?” (3)

D. Other interpretations?

Although Medusa is a product of ancient Greek religions, she contains eternal human truths: she can help us understand the power of rage to protect ourselves, and she can help us begin to understand how people who look different from us may see us as monstrous when we see ourselves as good and powerful. And perhaps, as Robert Graves believed, Medusa had some basis in actual fact.

Notes:

(1) Robert Graves, The White Goddess, amended and enlarged edition (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1948), p. 231.

(2) Emily Culpepper, “Ancient Gorgons: A Face for Women’s Contemporary Rage,” (Cambridge, Mass.: Woman of Power: A Magazine of Feminism, Spirituality, and Politics, 1986), reprinted in: Marjorie Garber and Nancy J. Vickers, ed., The Medusa Reader (New York: Routledge, 2003), pp. 243-245.

(3) Dorothea Smartt interviewed by Lizbeth Goodman, “Who’s Looking at Who(m): Re-viewing Medusa (1996), reprinted in Garber and Vickers, pp. 261 ff.

LEADER RESOURCE: A poem about Medusa

In 1971, the Unitarian Universalist poet May Sarton wrote a poem titled “The Muse as Medusa,” in which she explores the power of Medusa as a source of inspiration. The figure of Medusa helps May Sarton understand of her own inner being, her own soul. Somewhere in Sarton’s soul, she senses rage, a “secret, self-enclosed, and ravaged place,” and she realizes she must explore that rage, learn more about her inner self.

So Medusa helps May Sarton with one of the key tasks of a religious liberal: to “know thyself.”

I saw you once, Medusa; we were alone.

I looked you straight in the cold eye, cold.

I was not punished, was not turned to stone.

How to believe the legends I am told?

…

I turn your face around! It is my face.

That frozen rage is what I must explore.

Oh secret, self-enclosed, and ravaged place!

This is the gift I thank Medusa for.

May Sarton, A Grain of Mustard Seed: New Poems (New York: Norton, 1971), p. 38.

LEADER RESOURCE: Understanding Perseus

Many people see Perseus as the hero of the story: he is the one who conquers and kills Medusa, he is the one who overcomes Atlas. But we didn’t feel Perseus was a hero, so much as we felt that Perseus was a bully who wasn’t even very bright. As it turns out, our feeling about Perseus was anticipated by Pelaephatus, an ancient Greek writer. Pelaephatus was a religious naturalist — that is, he did not believe in supernatural explanations for religious matters. As a religious naturalist, Pelaephatus could not believe that Medusa’s head actually turned people to stone. Instead, he explained the story as follows:

“When he got his hands on the Gorgon, Perseus cut it in pieces; then, by way of fitting out his trireme, he put the head of the Gorgon on it and thereafter called the ship by the name ‘Gorgon.’ Sailing around in this ship he exacted money from the islanders and slew those who refused to give. In this way he sailed eventually against the people of Seriphos and demanded money from them. They in turn asked for a few days time in which to collect the money. But instead they brought together and set up man-sized [sic] stones in the marketplace and then abandoned the island of Seriphos. Perseus sailed back to demand his money, but when he came into the marketplace he found no men but rather the man-sized stones. Thereafter, whenever any of the other island people would not pay their tribute, Perseus would say: ‘Be careful that you too do not suffer what the people of Seriphos did, who say the Gorgon’s head and were turned to stone.'”

Pelaephatus, “The Daughters of Phorcys,” trans. Jacob Stern, On Unbelievable Tales: Translation, Introduction, and Commentary (Wauconda, Ill.: Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, 1996), p. 63.

In other words, Perseus was a thug, a murdering bully who traveled from island to island extorting money from innocent people. Not only that, but it appears that Perseus was so stupid he didn’t even realize that the people of Seriphos had tricked him.

In our view, and the view of Pelaephatus, the hero Perseus wasn’t at all heroic. The monster Medusa, on the other hand, is a figure of power, and a personage worth knowing — not in the least because knowing Medusa can help us to understand our selves.