From Many Lands

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2019 Dan Harper

8. The Accursed Lake

Long ago there was still a village east of the Eagle-Feather Mountains, where there lived a Hunter. One day, while out hunting, he followed the trail of an antelope until the trail ended in a large lake.

Just then, a fish thrust its head from the water and said, “Friend Hunter, you are on dangerous ground!” and off it went swimming.

Before the Hunter could recover from his surprise, a Lake-Man came up out of the water and said, “How is it that you are here, where no human ever came?”

The Hunter told his story, and the Lake-Man invited him to come in to his house. They entered the house by a trap-door in the roof, and climbed down a ladder. Inside, there were doors to the east, north, west, and south, as well as the door in the roof. Soon the Lake-Man learned that the Hunter had a wife and son at home.

“Why not come live with me?” the Lake-Man said. “I am no hunter, but I have plenty of other food. We could live very well here together.” And he showed the Hunter the four other huge rooms, all filled with corn and dried squash and the like.

“I will come with my wife and son in four days,” said the Hunter, “if the leader of my village will let me.”

So the Hunter went home, and his wife thought very well of the offer. The leader of his village did not want him to go, for he was the best hunter in all the pueblo, but at last gave permission.

So the Hunter and his wife and little boy came to the lake with all their property. The Lake-Man welcomed them, and they settled in. The Hunter went out hunting and brought back great quantities of game, and his wife took charge of the household, as was the custom of the Tiwa Indians in those days.

Some time passed very pleasantly. But at last the Lake-Man, who had an evil heart, pushed the Hunter into the East Room, locked the door and left him there to starve. The room was full of the bones of people whom he had tricked in the same way.

The boy was now old enough to hunt small game, and he brought home many rabbits. But the evil-hearted Lake-Man wanted to get him out of the way, too. One morning when the boy was about to start hunting, he heard his mother groaning as if about to die.

“Your mother is in terrible pain,” said the evil Lake-Man, “and the only thing that will cure her is sacred ice from the Lake of the Sun in the east.”

The boy said he would go get the ice, and started off toward the sunrise.

———

The boy walked over the brown plains until at last he came to the house of Old-Woman-Mole. She was there all alone, for her husband had gone to hunt. They lived in an old broken-down hut, and she was huddled trying to keep warm by a dying fire. But when the boy knocked, she rose and welcomed him kindly and gave him all there was in the house to eat: a tiny bowl of soup with a patched-up snowbird in it. The boy was very hungry, and picking up the snowbird bit a big piece out of it.

“Oh, my child!” cried the old woman. “You have ruined me! My husband trapped that bird these many years ago, but could never get another, and that is all we have had to eat ever since. So we never bit it, but cooked it over and over and drank the broth. And now not even that is left.” And she wept bitterly.

“Nay, Grandmother, do not worry,” said the boy, for he saw many snowbirds alighting nearby. Using his long hair, he made snares and soon caught many snowbirds. Then the Old-Woman-Mole was full of joy. After the boy told her his errand, she said:

“I shall help you. When you come into the house of the True People, they will offer you a seat, but you must not take it. They will try you with smoking the weer, but I will help you.”

With that, the boy started away to the east. At last, he came so near to Sun Lake that medicine men and guards of the True People saw him coming, and went in to tell the True People.

———

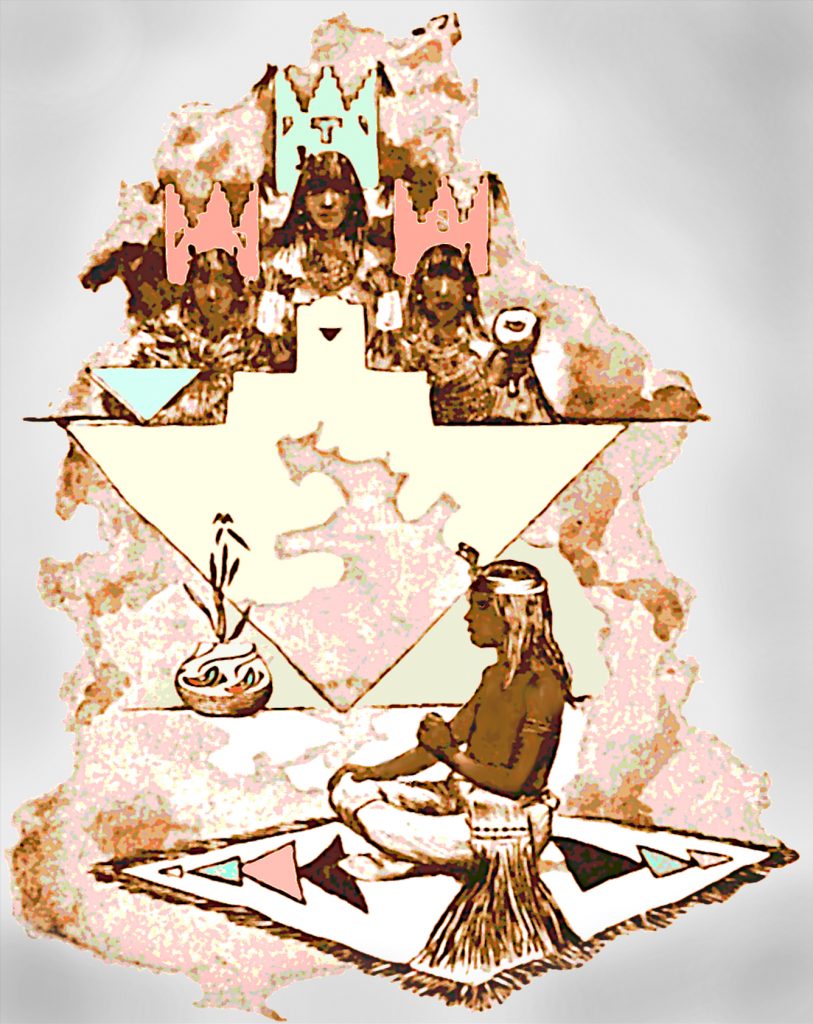

Above: The boy and the True People. Illustration by George Wharton Edwards (modified public domain image), based in part on photographs by Charles F. Lummis.

“Let him be brought in,” said the True People; and the guards brought the boy in through a magnificent building, until he stood in the presence of the True People in a vast room: white-colored gods of the East, blue gods of the North, yellow gods of the West, red gods of the South, and rainbow-colored gods of Up, Down, and Center. Beyond them were the sacred animals: the buffalo, the bear, the eagle, the badger, the mountain lion, the rattlesnake, and all the others that are powerful in medicine.

The True People offered the boy a white robe to sit on; but he declined respectfully, saying that he had been taught, when in the presence of his elders, to sit on nothing save what he brought, and he sat upon his blanket and moccasins. Then he told them that he had come for the sacred ice, to save his mother’s life.

The True People gave him a sacred weer, that is, a hollow reed filled with the magical plant pee-en-hleh, from the smoke of which the rain clouds come. The boy took in the poisonous smoke, but the Old-Woman-Mole dug a hole up to his toes, and the smoke went down through his feet into the hole, so no smoke went into his body, and no smoke escaped into the room of the True People.

“Surely he is our child,” said the True People to one another, “but we must test him again.” So they put him into the room of the East with the bear and the mountain lion, but he came out again unhurt. They put him into the room of the North, with the eagle and the hawk; into the room of the West, with the snakes; into the room of the South, with the Apaches and other human enemies of his people. He came forth from each room unhurt.

“Surely he is our child,” said the True People to one another, “but we must test him again.” They had a great pile of logs built up, set the boy on the top of the pile and lighted it. But in the morning, the boy sat there unharmed, saying, “I am cold and would like more fire.”

So the guards brought him inside, and the True People said: “You have proved yourself worthy of us, and now you shall have what you seek.”

They gave him the sacred ice, and he hurried home, stopping only to thank the Old-Woman-Mole.

———

When the evil Lake-Man saw the boy, he was very angry, for he had never expected him to return with the sacred ice. He pretended he was glad to see the boy, but said he must go to the gods of the South to get sacred ice there.

The boy walked south across the brown plains until he came to a drying lake. There, dying in the mud, was a little fish. Picking it up, the boy put it in his gourd canteen of water. After awhile he came to a good lake, and the fish in his gourd said, “Friend Boy, let me swim while you eat your lunch, for I love the water.”

So he put the fish in the lake; and when he was ready to go on, the fish came to him, and he put it back in his gourd. At three lakes he let the fish swim while he ate; and each time the fish came back to him.

Beyond the third lake began a great forest which stretched clear across the world, and was so dense with thorns and brush that no human being could pass through. The tiny fish changed itself into a great Fish-Animal with hard, strong skin, and bidding the boy mount upon its back, it went plowing through the forest, breaking down big trees like stubble, and bringing him through to the other side without a scratch.

“Now, Friend Boy,” said the Fish-Animal, “you saved my life, and I will help you. When you come to the house of the True People of the South, they will try you as they did in the East. When you have proved yourself, the leader of the True People will bring you his three daughters, from whom to choose you a wife. The two eldest are very beautiful, and the youngest is not; but choose the youngest, for she is good and the beauty of the older sisters does not reach to their hearts.”

The boy thanked the fish and went on.

At last he came to the house of the True People of the South. They tried him just as the True People of the East had done. Once again he passed the tests, and they gave him the sacred ice. Then the leader of the True People brought his three daughters, and said, “You are now old enough to have a wife, and I see that you are someone who cares for those around him. Therefore, choose one of my daughters to marry.”

The boy remembered the words of his fish friend, and said, “I choose your youngest daughter.”

The leader of the True People was pleased, and the boy and the youngest daughter were married. They started home, carrying the sacred ice and many presents. With the help of the Fish-Animal, they got through the forest, and walked on.

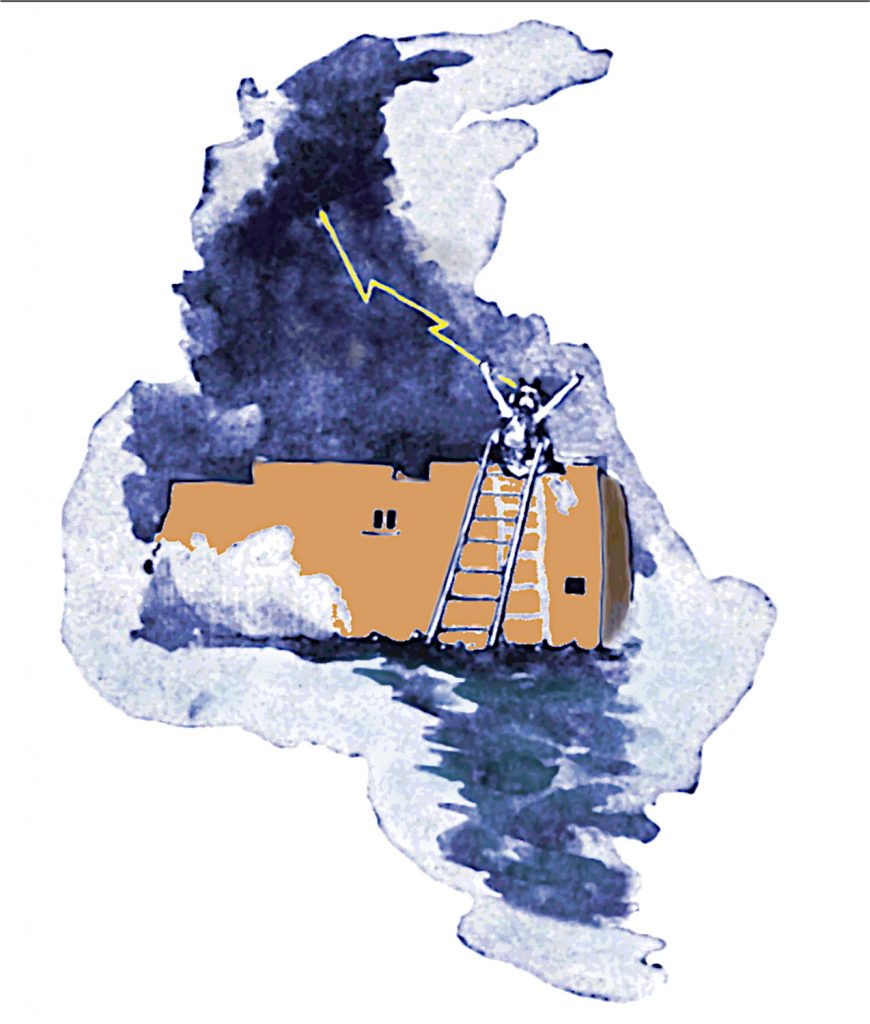

At last they came in sight of the big lake, and over it were great clouds, with the forked lightning leaping forth. They could see the evil Lake-Man sitting at the top of his ladder, watching to see if the boy would return, and as they watched the lightning of the True People struck him dead.

So the boy and the youngest daughter found the boy’s mother, and the three of them left the house of the evil Lake-Man. They left all the belongings of the evil Lake-Man behind, and when they got to the shore of the lake, the boy stood and prayed to the True People that the lake might be accursed forever. From that day its waters turned salt, and no living thing has drunk from it from that day to this.

Above: The evil Lake-Man being struck by lightning. Illustration by George Wharton Edwards (modified public domain image), based in part on photographs by Charles F. Lummis.

SESSION 8: “The Accursed Lake”

Top-level educational goals:

(1) Have fun and build community;

(2) Increase religious literacy;

(3) Build skills associated with liberal religion, e.g., interpersonal skills, introspection, basic leadership, being in front of a group of people, etc.

Educational objectives for this session:

(1) Get to know other people in the class;

(2) Hear a story from this religious tradition;

(3) Be able to talk about one or more incidents or themes from the story, e.g., if parents ask what happened in Sunday school today.

Preparation:

If you want to play the game “Patol House”: (A) If you are teaching at UUCPA, borrow the game from the closet in Room 8. (B) If you are teaching in another setting, make the game from the enclosed PDFs.

If you want to have a teen who has gone through the Coming of Age program visit your class, make sure you invite them a week in advance.

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story “The Accursed Lake.”

See above.

III/ Imagining the Boy’s ceremony with the True People.

Here’s what you need to know about this activity BEFORE you lead it:

The scene in the story where the True People test the boy reveals a great deal about the relationship between humans and deities in this mythos. The text is imbued with a sense of ceremony, to the point where this becomes sacred ritual. In Protestant Christianity, the religious form most familiar to most people in the United States, correct belief is most important to God; but in this story, correct ritual action is most important to the True People.

The point of acting out this ceremony is to have the children begin to understand that in some religious traditions, ritual is more important than belief — furthermore, relationship is more important than belief. The Boy does NOT have to affirm that the True People are really true; instead, the Boy has to do the correct ritual actions. And again, the Boy does NOT have to affirm that the True People are really true; what the Boy has to do is maintain a correct and respectful relationship with the True People.

Actually, this concept may be easier for the children to accept than for many of us adults to accept. Many of us adults automatically assume that all religion is all about belief. Protestant Christianity may be all about belief, but that is NOT true of many other religions! Don’t think of the True People as equivalent to the Protestant Christian God, a supernatural being that requires of you your belief. Instead, try thinking of the True People as psychological entities similar to what psychologist Carl Jung called the “collective unconscious.” This is still imposing a Western perspective on a non-Western religious tradition, but it works better than trying to make the True People into the God of Protestant Christianity.

OK, now here’s the activity:

Tell the children the other teacher will be the Boy (or if you invited a teen visitor, you ask them if they’d be willing to play the part of the Boy). The children are going to be the True People. If the other teacher (or teen visitor) can pass all the tests, then the children (as the True People) will give them the sacred ice. Have them sit as in the illustration above, with some on the floor, some in chairs, some standing; or have them sit in a semi-circle; whatever feels most ceremonial to you and them.

Once the children are placed as the True People, have the other adult enter as the Boy (or Girl, or Non-Binary Person, etc.). Prompt the children as they test the other adult:

— they should offer the adult a blanket

— they should let the adult request the sacred ice

— they should test the adult with the weer filled with the poisonous pee-en-hleh

— they should test the adult with the room of the East (bear and mountain lion)

— they should test the adult with the room of the North (the eagle and hawk)

— they should test the adult with the room of the West (snakes)

— they should test the adult with the room of the South (human enemies)

— they should test the adult with the sacred fire

IV/ Conversation about the story

Your conversation will be most interesting if your fellow teacher remembers to FAIL some of the tests — especially the first test, by accepting the True People’s offer of a blanket to sit on. If the Boy in the story had failed any of the tests, what do you think would have happened? What should happen to your fellow teacher, if they fail one of the tests?

To go deeper into this topic, you can say to the children that most cultures have rituals for children and teenagers, in which the children or teens have to prove themselves in some way. Examples from other religions: Jewish teens may go through a bar mitzvah or bat mitzvah, where they learn Hebrew and read their Torah portion in Hebrew to their congregation. Teenaged Baptists can accept Jesus as their Lord and Savior, and undergo the ritual of full-immersion Baptism. The Ohlone people of north coastal California had sweat lodges for prayer and purification, and entering the sweat lodge for the first time was a rite of passage for a boy (some contemporary Ohlones are reviving the practice of the sweat lodge). N.B.: I was unable to find any reliable account of an adolescent rite of passage for Tiwa Indians.

Ask the children: Do you think it is a good idea for children or teens to go through a ritual at a certain age? Would YOU like to prove yourself by going through a ritual? (Opinions among the children will probably differ on both these questions.) What do you think should happen in that ritual?

Now tell the children that when they get to 8th or 9th grade, they can choose to go through the Coming of Age program in our congregation.

IF YOU INVITED A GUEST, a teen who went through the Coming of Age program, have them tell the children about the Coming of Age program now.

Otherwise, explain to the children: In the Coming of Age program, they can think about who they are as religious persons, and then they will write that out — a statement of religious identity — and read it out loud to the whole congregation at a Sunday service. (You might say this program is not at all like the True People asking the Boy to inhale the poisonous pee-en-hleh smoke.)

V/ Playing a ceremonial game

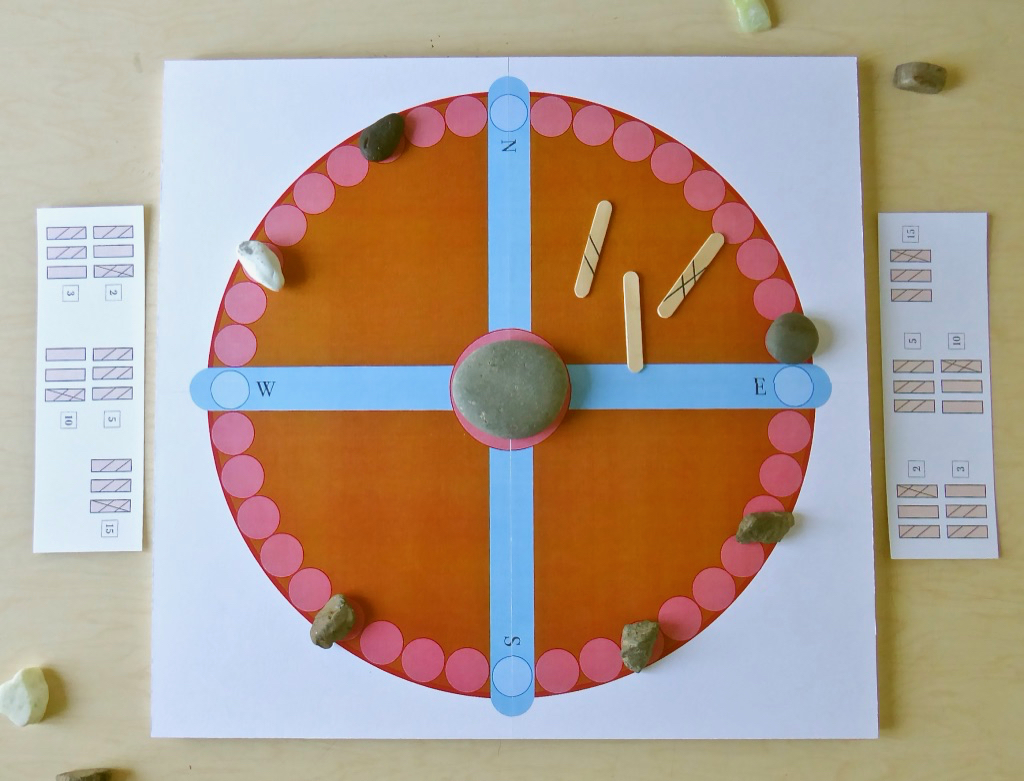

If you have time, play Patol House (and invite your teen visitor to stay and play with you). This is an adaptation of a traditional horse race game of the Tiwa Indians of New Mexico and Texas. This game was played with a great amount of ceremony, so when you play, think about how to make this ceremonial. (Note, however, that one thing forbidden during this game was singing, so don’t make singing part of your ceremony.)

Needed for the game:

The traditional game was set up using stones for the game board, carved counting sticks, and forked sticks for the “horses,” or playing pieces. In our modernized version, we have a printed game board, counting sticks made out of modified popsicle sticks, and stones for the “horses” or playing pieces. See photo below.

Using the counting sticks:

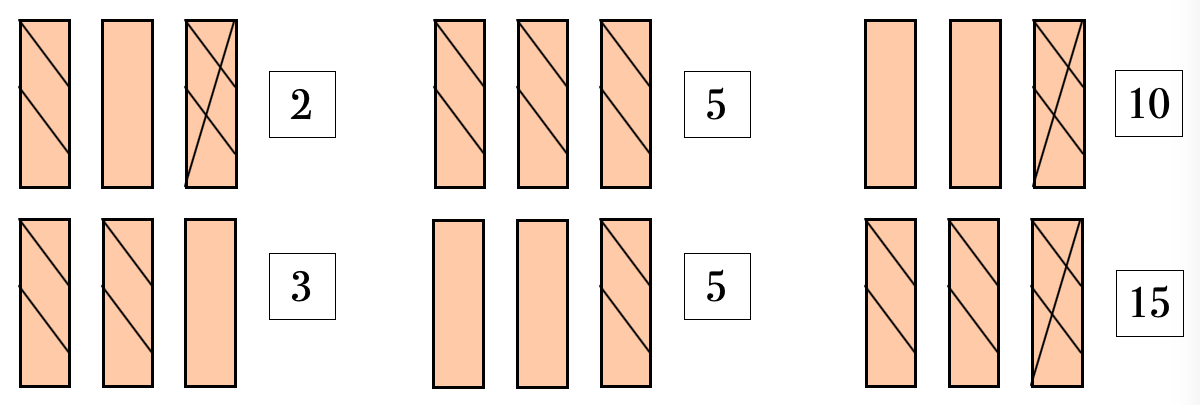

Hold the three counting sticks level with your chin in your right hand. Bring your hand down, and release the sticks 6 to 8 inches above the center circle on the game board (but no closer than 6, see “Strategy” below). The sticks hit the center circle, and fall with one face or another showing. The diagram below shows how many spaces you may move your horse, depending on which sides of the counting sticks are showing:

Game play:

Each player throws the counting sticks, the one with the highest points goes first.

The first player throws the counting sticks, and starting from the blue circle nearest to where they are sitting, moves their horse that number of spaces. Players may move either clockwise or counterclockwise as they wish, but once they begin moving in one direction they must keep moving in that direction in subsequent turns. However, if they throw a 10, this would place their horse in a river, which is not allowed, so they should throw the counting sticks again until they throw a number that will not land them in a river.

The next players may begin from the same river that the first player started from, or from a different river. They may move either clockwise or counterclockwise, but once they begin moving in one direction they must keep moving in that direction.

Player’s horses may pass over other players horses. However, if one player’s horse ends up on the space occupied by another player’s horse, the other player’s horse is considered dead and must return to the circle where they started, and start again. A player may have to start over several times during the course of a game.

If you start over, you must start in the same river you started in before. However, if you start over, you can choose to go either clockwise or counterclockwise (but once you choose a direction, you have to keep going in that direction, unless you have to start over again).

Winning the game:

The first player whose horse makes it all the way around the circle, back to their starting point or past it, wins the game.

Variations:

(1) If you’re playing with 4 to 7 players, each player has two horses, and takes a separate turn for each horse.

(2) No-kill version: two horses can occupy the same space; in other words, if a player’s horse lands on another player’s horse, that horse is not considered dead and does not return to their starting point. This version of the game can be boring, but might be worth doing the first time you play.

Strategy:

This may seem like a game of chance, but it is really a game of skill. A skilled player can hold the sticks in their hand and bounce them in such a way as to get the number they want. This works best if you can find a flat stone to fit in the center circle, as the sticks will bounce better off of a slightly rounded stone than off the game board (see photo).

Players should be careful to release the sticks a full 6 inches above the stone or center circle — you must release your hold before they hit.

How To Play Patol House (printable PDF)

How to make the Patol House game:

1. Print out the 11 by 17 inch game board PDF, cut it in half, and enlarge each half 2x on a color photocopier. Trim the halves so that they fit together, and glue to card stock to make the game board.

2. Find a dozen small stones for the “horse,” or playing pieces. Find a larger flat stone for the center, something to drop the throwing sticks on.

3. Mark three popsicle sticks to make the counting sticks. Trim to length, and round the edges (see the photo).

4. Print out scoring cards (use the image above, in the rules for the game).

VI/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle by touching toes, or touching elbows.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about Guru Nanak, right?” You’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

Say the closing words together — either these words, or others you choose:

Go out into the world in peace

Be of good courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return no one evil for evil

Strengthen the fainthearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Rejoice in beauty

Speak love with word and deed

Honor all beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

LEADER RESOURCES AND BACKGROUND:

Source: Charles Fletcher Lummis, Pueblo Indian Folk-Stories (New York: D. Appleton-Century Co., 1910), pp. 109-116. Tales of the Tiwa Indians of New Mexico and Texas.

Additional resources:

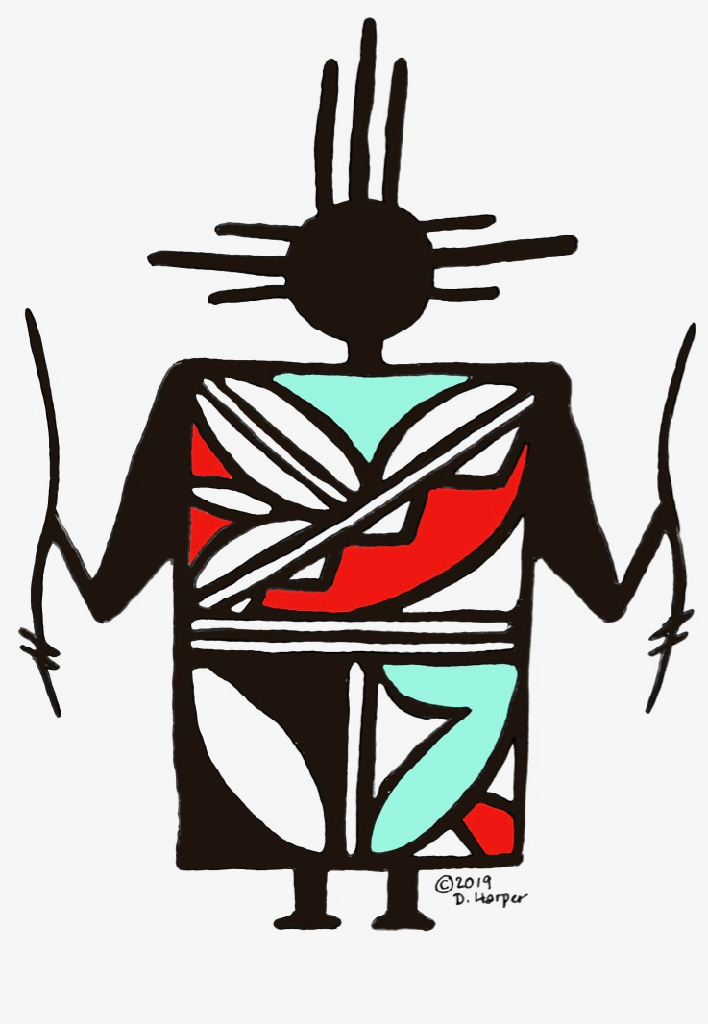

Coloring page of a Tiwa figure for The Accursed Lake (PDF).

Above: Drawing of a figure from a vase made c. 2015 by Albert Alvidrez, member of the Ysleta Del Sur Pueblo — Tigua Indian Reservation.