From Many Lands

A curriculum for middle elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2020 Dan Harper

5. The Pool of Enchantment

One day, King Yudhisthira and his four brothers found that the wooden blocks they needed to light a sacred fire had been stolen by a deer. which had stolen the wooden blocks which a Brahmin needed so he could light the sacred fire. The king and his brothers went deep into the forest to find the deer. They searched for a long time. They grew thirsty, but could not find any water. At last, completely tired out, they sat down under a tall tree.

“If we do not find water soon, we shall die,” said Yudhisthira. Turning to his brother Nakula, he said, “Brother, climb the tree to see if there is any water nearby.”

In a few moments Nakula had climbed the tree, and he called down, “I see trees which only grow near running water. there I hear the sound of cranes, birds which love the water.”

“Take the arrows out of your quiver,” said Yudhisthira. “Go fill your quiver with water, and bring it back to quench our thirst.”

Nakula set out, and quickly found a small stream which widened into a pool of clear water. A crane stood on the far side of the pool.

Above: The Crane standing at the edge of the water

Nakula knelt down at the edge of the water to drink, but just then a stern Voice said:

“Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

Nakula was thirsty, so he ignored the Voice. He drank eagerly from the cool water, and in a few moments lay dead at the edge of the pool.

———

Nakula’s four brothers patiently waited for him to return. At last Yudhisthira said, “Sahadeva, go find your brother. Then fill your quiver with water, and bring it back to quench our thirst.”

Sahadeva walked off through the forest. Soon he found Nakula lying dead at the edge of the pool. Before looking to see what had killed his brother, he knelt down at edge of the water to drink. Just then, a stern Voice said:

“Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

But Sahadeva had already drunk from the water, and lay dead at the edge of the pool.

———

Once again the remaining brothers waited patiently. At last Yudhisthira said to his brother Arjuna, the mighty archer, “Go find our brothers. Then fill your quiver with water, and bring it back to quench our thirst.”

Arjuna slung his bow over his shoulder, and with his sword at his side walked to the pool. When he saw his brothers lying dead among the reeds, he fitted an arrow to his bow while his keen eyes pierced the darkness of the forest searching for the enemy who had killed them. Seeing neither human nor wild beast, he knelt down at the edge of the pool to drink. Just then, a stern Voice said:

“Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

Prince Arjuna looked about him. “Come out,” he cried, “and fight with me.” He shot arrows in all directions, but the Voice only laughed and repeated its command.

But Arjuna knelt and drank, and soon lay dead at the edge of the pool.

———

Yudhisthira waited patiently, but when Arjuna did not return he said to Bhima, “Go find our brothers. Then fill your quiver with water, and bring it back to quench my thirst.”

Bhima silently rose, walked to the pool, and found his brothers lying dead. “What evil demon has killed my brothers,” he thought to himself, looking around. But he was so thirsty he knelt to drink. Just then, a stern Voice said:

“Do not drink, O Prince, until you have answered my questions.”

Bhima did not hear the Voice, and soon he lay dead beside his brothers.

———

Yudhisthira waited for a time. At last he went himself to find water.

When he came to the pool, he stood for a moment looking at it. He saw clear water shining in the sunlight, lotus flowers floating in the water, and a crane stalking along the far edge of the pool. There were his four brothers lying dead at the edge of the water.

Above: Yudhisthira and the Crane

Even though he was terribly weak and thirsty, he stopped and spoke aloud the name of each of his brothers, and told of the great deeds each had done. He spoke aloud his sorrow for the death of each one.

Then he thought to himself, “This must be the work of some evil spirit. Their bodies show no wounds, nor is there any sign of human footprints. The water is clear and fresh, and I can see no signs that they have been poisoned. But I am so thirsty, I will kneel down to drink.”

———

As King Yudhisthira knelt down, the Voice took the shape of a crane, a Baka, a gray bird with long legs and a red head. The Baka spoke to him in a stern voice, saying:

“Do not drink, O King, until you have answered my questions.”

“Who are you?” said Yudhisthira. “What do you want?”

“I am not a bird, but a Yaksha!” said the crane. Yudhisthira saw the vague outlines of a huge being above crane, towering above the lofty trees, glowing like an evening cloud.

“It seems I must obey, and answer your questions before I drink,” said the king. “Ask me what you will, and I will use what wisdom I have to answer you.”

So the Yaksha who disguised as a crane began asking question after question:

The Yaksha said: “What makes the sun move around the sky?”

The King replied: “The Dharma — right behavior, duty and law — sets the Sun.”

The Yaksha said: “What is the true nature of the Sun?”

The King replied: “Truth is the true nature of the Sun.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is heavier than the earth, and higher than the heavens?”

The King replied: “The love of parents is both heavier than earth and higher than the heavens.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is faster than the wind?”

The King replied: “A person’s thoughts are faster than the wind.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is it, that when you cast is aside, makes you lovable?”

The King replied: “When you cast aside pride, you become lovable.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is it, that when you cast it aside, makes you happy?”

The King replied: “When you cast aside greed, you become happy.”

The Yaksha asked: “What is the most difficult enemy to conquer?”

The King replied: “Anger is the most difficult enemy to conquer.”

The Yaksha asked: “What sort of person is most wicked?”

The King replied: “The person who has no mercy is most wicked.”

The Yaksha asked: “What sort of person is most noble?”

The King replied: “The person who desires the well-being of all creatures is most noble.”

———

Yudhisthira was able to answer all the questions wisely and well. At last the Yaksha stopped asking questions, and revealed who he was. He was Yama-Dharma, the god of Death — and Yudhisthira’s father.

“It was I who took on the shape of a deer and stole the wooden blocks, so you would have to come look for me,” Yama said. “Now you may drink. And you may also choose which of your four brothers shall be returned to life.”

“Bring Nakula back to life,” said Yudhisthira.

“Why not the other three?” said Yama.

“My brother Nakula’s mother is Madri,” said the King. “Kunthi is the mother of rest of us. If you bring Nakula back to life, then both Madri and Kunthi will still have a son — Madri will have Nakula, and Kunthi will have me. Therefore, let Nakula live.”

“Truly you are called ‘The Just,” said Yama as he began to fade away. “Noblest of kings and wisest of all persons, for your wisdom and your love and your sense of justice, I shall return all of your brothers to life.”

SESSION 5: “The Pool of Enchantment”

Top-level educational goals:

(1) Have fun and build community;

(2) Increase religious literacy;

(3) Build skills associated with liberal religion, e.g., interpersonal skills, introspection, basic leadership, being in front of a group of people, etc.

Educational objectives for this session:

(1) Get to know other people in the class;

(2) Hear a story from this religious tradition;

(3) Be able to talk about one or more incidents or themes from the story, e.g., if parents ask what happened in Sunday school today.

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

II/ Read the story

Read “The Pool of Enchantment” to the children.

III/ Acting out the story

This story, with all its death scenes, is definitely worth acting out.

Ask: “Who are the characters in this story?” The two main characters are Yudhisthira and Yama, god of Death. Other characters include Yudhisthira’s four brothers: Nakula, Sahadeva, Arjuna, and Bhima. There is a Crane that turns into Yama. (There is also a disembodied Voice that turns out to be Yama, but since that is a spoken part only, the teacher reading the story will be the Voice.)

Determine where the stage area will be. If there are any children who really don’t want to act, they can be part of the audience with you; you will sit facing the stage.

The lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. The lead teacher may wish to simplify the story on the fly, to make it easier to act out; and the lead teacher may want to turn several of the characters into different genders.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group. Go over the story to make sure the children understand it. Now ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

Here’s a question specific to this story that you may want to use:

“Why do you think that Yama made the brothers die if they didn’t answer his questions?” There are lots of obvious answers to this question—because he’s god of death, because it makes for a good story, etc. — but one answer may not be so obvious to Americans of the early 21st century: Because it’s Fate. In the Mahabharata, from which this story comes, sometimes things happen because they are fated to happen. Instead growing out of the cause-and-effect purposefulness of contemporary American thinking, this story is rooted more in chance and fate.

Next, talk a little about the truth of the story:

“How true is this story: completely true facts, maybe some truth, maybe a little bit of truth, or more like a fairy tale?” (Note to teachers: There was no actual king named Yudhisthira, but so many people know and love this story — it has inspired books, plays, television shows, movies, video games — it sometimes seems as though Yudhisthira were a real person.)

To finish up, you might say something like this:

“None of the characters in this story actually lived and this story isn’t factually true; yet this is a story that talks about things that are true. This story is really asking a big question — ‘What is the right way to live?’ — and making that big question a part of a story that’s interesting to listen to.”

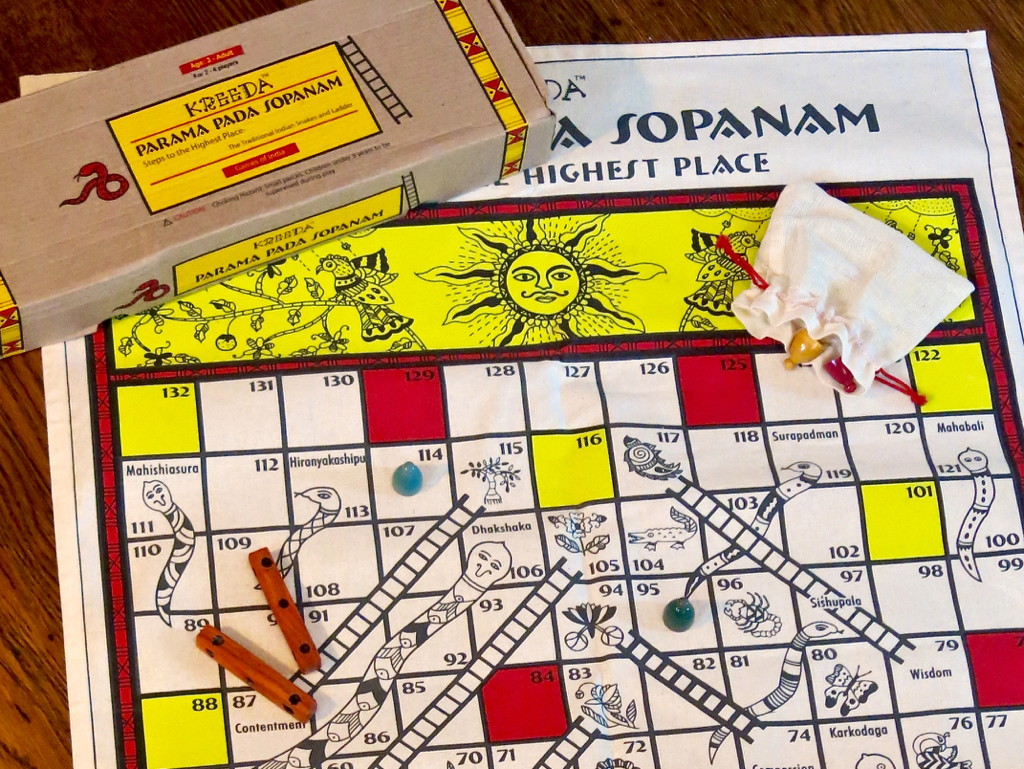

V/ Play a game from India

Play the classic Indian game, variously called Moksha Patam, Parama Pada Sopanam, etc. (on which the Western game “Chutes and Ladders” is based). This game represents a life journey where one can be set back by failings like greed, etc., which are represented in the game by snakes down which you slide — or one can advance by means of virtues, which are represented in the game by ladders. There is no skill involved in playing these games; instead, luck, or fate, determine who is the eventual winner.

A beautiful modern version of Parama Pada Sopanam is made in India by Kreeda. If you are teaching this curriculum at UUCPA, two copies of this game are stored in the closet in room 8. Or you may use an alternate game, Moksha Patam; instructions for making this game are here.

Allow about 15 minutes for this game (and even then, chances are you won’t finish). If you have a lot of children, have two groups playing separate games, with a teacher at each table to read aloud the stories relating to the snakes.

Above: Parama Pada Sopanam, published by Kreeda Games, India

VI/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers, e.g.: “What did we do today? We heard a story, right? Anyone remember what the story was about? It was about an Enchanted Pool, right?” As always, you’re not trying to put any one child on the spot, but rather drawing on the wisdom of the group as a whole. If you’re sending puppets home with children, remind them what each character did in the story.

If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

Say the closing words together:

Go out into the world in peace

Be of good courage

Hold fast to what is good

Return no one evil for evil

Strengthen the fainthearted

Support the weak

Help the suffering

Rejoice in beauty

Speak love with word and deed

Honor all beings.

Then tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

LEADER RESOURCES AND BACKGROUND:

1. Source of the story

This story appears as an incident in the Mahābhārata. Adapted from The Indian Story Book: Containing Tales from the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, and Other Early Sources, by Richard Wilson (London: Macmillan & Co., 1914).

The illustration of the Crane is a digitally enhanced copy of a Sarus Crane (Antigone antigone) from H. E. Dresser, A History of the Birds of Europe, London: 1871-1881.

2. Pronunciation

This guide does not attempt to provide proper Sanskrit pronunciation, but is merely a “good enough” guide for American English speakers.

Mahābhārata = mah hah BAH rah tah

Arjuna = AR joo nah

Bhima = BEE mah

Yama Dharma = YAH mah DAHR mah

Nakula = NAH koo lah

Sahadeva = SAH hah day vah

Yudhisthira = Yoo THISH theer ah

3. Why the Mahābhārata is important

“Quite simply, the Mahābhārata is a powerful and amazing text that inspires awe and wonder. It presents sweeping visions of the cosmos and humanity and intriguing and frightening glimpses of divinity in an ancient narrative that is accessible, interesting, and compelling for anyone willing to learn the basic themes of India’s culture. The Mahābhārata definitely is one of those creations of human language and spirit that has traveled far beyond the place of its original creation and will eventually take its rightful place on the highest shelf of world literature beside Homer’s epics, the Greek tragedies, the Bible, Shakespeare, and similarly transcendent works.”

—Professor James L. Fitzgerald, Das Professor of Sanskrit, Department of Classics, Brown University

4. Contemporary interpretations of this story

The Mahābhārata has permeated popular culture, not only in India, but throughout the world. A very little Web searching will bring up many contemporary interpretations of this story of Yudhisthira at the lake — a search for “Yaksha Prashna” or “Yudhisthira at the lake” will lead you to interpretations of the riddle contest from scholars, bloggers, devout Hindus, etc. You will also find all sorts of ancillary myths, e.g., the enchanted pool was formed by Lord Shiva’s tears.

If you’re teaching this curriculum at UUCPA, a comic book version of the story is available to borrow.

None of the videos below is worth showing to a class of middle elementary children, but they are worth skimming for the adult who wants to learn more about how the story is interpreted in popular culture.

1. A television adaptation of the story from India. While there are minor differences in the plot, the general story line is similar to the story in this curriculum:

youtube.com/watch?v=9qhHXMRqP2s

2. A cartoon version from India. Even though the dialogue is in Hindi, you can get the gist of the story. The story line appears to be quite close to the story in this curriculum. Skip ahead to 5:30 to cover the part of the story that’s in this curriculum:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=arKfWOH3j5U

3. A stage version from England. Peter Brook, a British theatre and film director from England, created a nine-hour stage play based on the Mahābhārata. Reduced to six hours, a film version was released in 1989 to television. This excerpt shows Brook’s interpretation of the encounter at the enchanted pool:

youtube.com/watch?v=LjxSvdC0mCg

5. More riddles from the story

Middle elementary children have typically begun to enjoy riddles, but the riddles in this story are somewhat advanced for children in this age group.

Nevertheless, if the children are curious about the riddles in the story, here are two dozen more of the riddles (and their answers) that Yama asked of Yudhisthira in the original story.

The riddles are separated according to type: puzzle riddles, riddles about living the good life, and riddles relating to Hindu belief and morality.

PUZZLE RIDDLES

These puzzle riddles will probably be what interest this age group.

What is best for farmers?

Rain is best for farmers.

Who does not close their eyes when sleep-ing?

Fish do not close their eyes when sleeping.

What does not move even after birth?

Eggs do not move even after birth.

What does not have a heart?

A stone does not have a heart.

What grow as it goes?

A river grows as it goes to the sea.

Who is the guest who is welcome to all?

Fire is the guest who is welcome to all.

Who travels alone?

The Sun travels alone.

Who is born again and again?

The Moon is born again and again.

What container can contain everything?

The Earth can contain everything.

RIDDLES ABOUT LIVING A GOOD LIFE

(These riddles may be of interest to this age group, but may require adult explanation.)

How may a person become secure?

A person becomes secure through courage.

How may a person become wise?

A person gains wisdom by living with people who are wise.

Out of all things, what is best?

Out of all things, knowledge gained from wise people is best.

Out of all blessings, what is best?

Out of all blessings, good health is best.

Out of all pleasures, what is best?

Out of all pleasures, being contented is best.

RIDDLES ABOUT HINDU BELIEF AND MOR-ALS:

These riddles require enough knowledge of Hinduism that they will likely be difficult to understand for many American children in this age group.

What makes the sun move around the sky?

Correct behavior [the Dharma], duty, and law move the Sun around the sky.

What is best for the Brahmans (those who pursue learning as their life’s work)?

Studying the Vedas, the holy books, is best for the Brahmans.

(This riddle is based on the Hindu caste system; Brahmans are the highest caste, or class.)

What is best for the Kshathriyas (those who are the warriors and defenders)?

Weapons are best for the Kshathriyas.

(This riddle is related to the Hindu caste system; warriors are the second-highest caste.)

Out of all just actions, which is best?

Out of all just actions, non-violence is best.

What must a person control in order to never be sad?

A person must control their mind in order to never be sad.

What will a person never be sad to leave be-hind?

A person will never be sad to leave behind anger.

What is it, that when you cast it aside, makes you lovable?

When you cast aside pride, you become lovable.

What is it, that when you cast it aside, makes you happy?

When you cast aside greed, you become happy.

What should a person leave behind to become rich?

A person should leave behind desire in order to become rich.

What should a person leave behind to be have a happy life?

A person should leave behind selfishness to have a happy life.

By what is the world covered?

The world is covered by ignorance.

Why doesn’t the world shine brightly?

Bad behavior keeps the world from shining brightly.

What is surprising?

It is surprising that we think of ourselves as stable and permanent, when every day we see beings dying.

N.B.: Different versions of the Mahābhārata, and different translations of the Mahābhārata, will have different versions of these riddles.

6. More about the Mahābhārata

If this story has gotten you interested in the Mahābhārata, Professor James L. Fitzgerald has a Web site with an excellent introduction:

www.brown.edu/Departments/Sanskrit_in_ Classics_at_Brown/Mahabharata/index.shtml