Beginnings: Myths and stories from world religions

A curriculum for upper elementary grades by Dan Harper

Copyright (c) 2014, 2024 Dan Harper.

Back to Table of Contents | On to Session 4

The Golden Chain: A Story from the Yoruba Tradition

The Yoruba peoples have lived in West Africa for more than fifteen hundred years. They were perhaps the most advanced civilization in Africa for much of their history; both their art and technology were superior to their neighbors.

During the years when West African peoples were captured and sold into slavery, there were many Yoruba people who were sold into slavery in North and South America and in the Caribbean islands. The Yoruba people brought their religious traditions to the Americas, and continued to worship their own gods and goddesses.

The Yoruba religions adapted some parts of Christianity, which was the religion of their masters, into their own religion. They may have done this to help keep their own religion secret from their masters.

Over time, the Yoruba religion came to be known by different names in different places. It is called Santeria in the Caribbean, Vodoun in Haiti, Candomble in Brazil, and Oyotunji in the United States. But all these different traditions give devotion to the orishas. An orisha is a heavenly being, like a god or goddess. Each orisha is identified with a Roman Catholic saint.

Olorun is the highest god, but human beings do not have direct contact with Olorun. Instead, human beings find ways of contacting the orishas, who in turn can contact Olorun. When a person needs help, she or he will visit a diviner who will offer advice on what to do. Often, the diviner will read the palm nuts, a traditional way of connecting with the orishas. Human beings also “make ebo” — offer sacrifices — at the shrine of one of the orishas, seeking the support and help of that ebo.

The following story, “The Golden Chain,” is one of many creation stories told by the followers of the orishas.

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported by Isha; photo cropped and edited for clarity.

The Golden Chain

Long ago, well before there were any people, all life existed in the sky. Olorun lived in the sky, and with Olorun were many orishas. There were both male and female orishas, but Olorun transcended male and female and was the all-powerful supreme being. Olorun and the orishas lived around a young baobab tree. Around the baobab tree the orishas found everything they needed for their lives, and in fact they wore beautiful clothes and gold jewelry. Olorun told them that all the vast sky was theirs to explore. All the orishas save one, however, were content to stay near the baobab tree.

Obatala was the curious orisha who wasn’t content to live blissfully by the baobab tree. Like all orishas, he had certain powers, and he wanted to put them to use. As he pondered what to do, he looked far down through the mists below the sky. As he looked and looked, he began to realize that there was a vast empty ocean below the mist. Obatala went to Olorun and asked Olorun to let him make something solid in the waters below. That way there could be beings that Obatala and the orishas could help with their powers.

Touched by Obatala’s desire to do something constructive, Olorun agreed to send Obatala to the watery world below. Obatala then asked Orunmila, the orisha who knows the future, what he should do to prepare for his mission.

CC BY 3.0 Sailko. Photo cropped, lightly edited for clarity.

Orunmila brought out a sacred tray and sprinkled the powder of baobab roots on it. He tossed sixteen palm kernels onto the tray and studied the marks and tracks they made on the powder. He did this eight times, each time carefully observing the patterns. Finally he told Obatala to prepare a chain of gold, and to gather sand, palm nuts, and maize. He also told Obatala to get the sacred egg carrying the personalities of all the orishas.

Public domain image by Toluaye.

Obatala went to his fellow orishas to ask for their gold, and they all gave him all the gold they had. He took this to the goldsmith, who melted all the jewelry to make the links of the golden chain. When Obatala realized that the goldsmith had made all the gold into links, he had the goldsmith melt a few of them back down to make a hook for the end of the chain.

Meanwhile, as Orunmila had told him, Obatala gathered all the sand in the sky and put it in an empty snail shell, and in with it he added a little baobab powder. He put that in his pack, along with palm nuts, maize, and other seeds that he found around the baobab tree. He wrapped the egg in his shirt, close to his chest so that it would be warm during his journey.

Obatala hooked the chain into the sky, and he began to climb down the chain. For seven days he went down and down, until finally he reached the end of the chain. He hung at its end, not sure what to do, and he looked and listened for any clue. Finally he heard Orunmila, the seer, calling to him to use the sand. He took the shell from his pack and poured out the sand into the water below. The sand hit the water, and to his surprise it spread and solidified to make a vast land. Still unsure what to do, Obatala hung from the end of the chain until his heart pounded so much that the egg cracked.

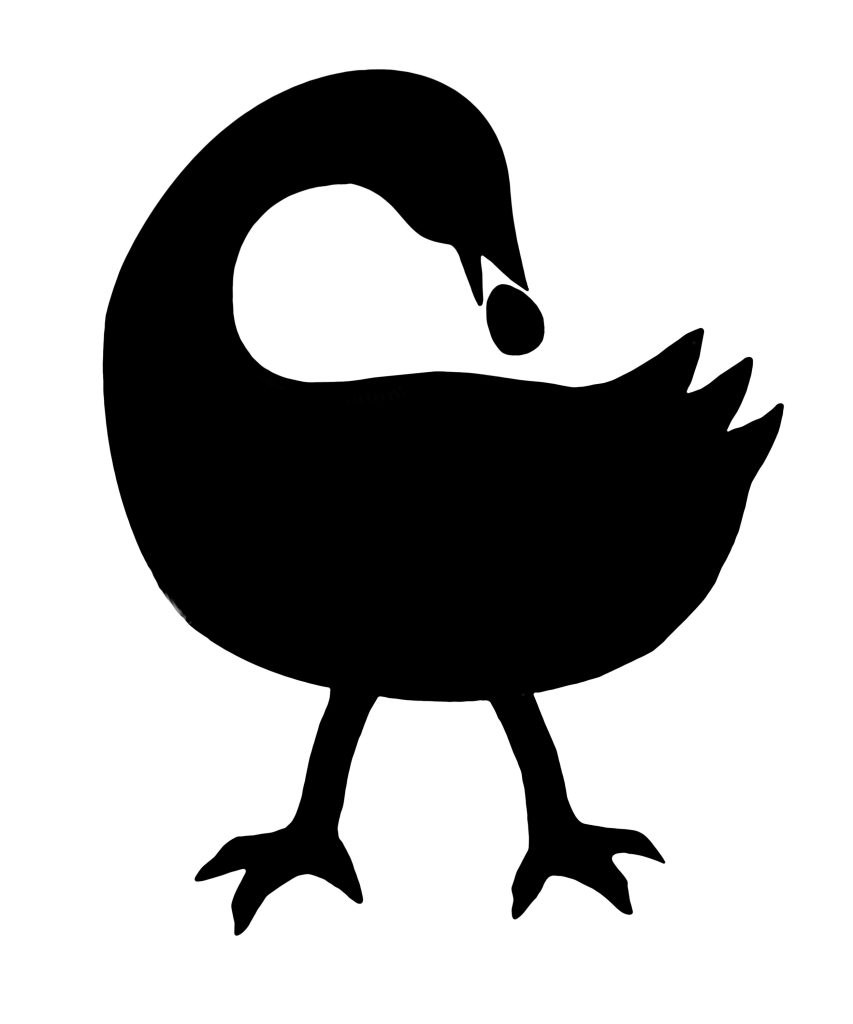

From it flew Sankofa, the bird bearing the sprits of all the orishas.

CC BY 3.0 Brooklyn Museum. Photo cropped and edited for clarity.

Like a storm, the orishas blew the sand to make dunes and hills and lowlands, giving it character just as the orishas themselves have character.

Finally Obatala let go of the chain and dropped to this new land, which he called “Ife”, the place that divides the waters. Soon he began to explore this land, and as he did so he scattered the seeds from his pack, and as he walked the seeds began to grow behind him, so that the land turned green in his wake.

After walking a long time, Obatala grew thirsty and stopped at a small pond. As he bent over the water, he saw his reflection and was pleased. He took some clay from the edge of the pond and began to mold it into the shape he had seen in the reflection. He finished that one and began another, and before long he had made many of these bodies from the dark earth at the pond’s side. By then he was even thirstier than before, and he took juice from the newly-grown palm trees and it fermented into palm wine. He drank this, and drank some more, and soon he was intoxicated. He returned to his work of making more forms from the edge of the pond, but now he wasn’t careful and made some without eyes or some with misshapen limbs. He thought they all were beautiful, although later he realized that he had erred in drinking the wine and vowed to not do so again.

Before long, Olorun dispatched Chameleon down the golden chain to check on Obatala’s progress. Chameleon reported Obatala’s disappointment at making figures that had form but no life. Gathering gasses from the space beyond the sky, Olorun sparked the gasses into an explosion that he shaped into a fireball. He sent that fireball to Ife, where it dried the lands that were still wet and began to bake the clay figures that Obatala had made. The fireball even set the earth to spinning, as it still does today. Olorun then blew his breath across Ife, and Obatala’s figures slowly came to life as the first people of Ife.

Source and notes:

This creation story comes from the Yoruba people of Nigeria, Togo and Benin. In the religion of the Yoruba, the supreme being is Olorun, and assisting Olorun are a number of heavenly entities called orishas. This story was written down by David A. Anderson/ Sankofa, who learned it from his father, who learned it from his mother, and so on back through the Yoruba people and through time. The Origin of Life on Earth: An African Creation Myth, by David A. Anderson/Sankofa (Mt. Airy, Maryland: Sights Productions, 1991), 31 p. [Folio PZ8.1.A543 Or 1991].

Session Three: The Golden Chain

Materials

If you choose to play the mancala game, have enough game boards and playing pieces for all the children to play.

If you choose to do the art activity, you’ll need paper and drawing materials.

I/ Opening

Take attendance.

Light chalice with these words and the associated hand motions: “We light this chalice to celebrate Unitarian Universalism: the church of the open mind, the helping hands, and the loving heart.”

Check-in: Go around circle. Each child and adult says his or her name, and then may say one good thing and one bad thing that has happened in the past week (anyone may pass).

Review last week: If you took photos of last week’s skit, show them to the children, and have them help you post them on the class bulletin board (remember to leave lots of room on the class bulletin board for pictures from future classes).

II/ Read the story

Read “The Golden Chain” to the children.

III/ Act out “The Golden Chain.”

By now, the children should be fairly adept at acting out the story.

Ask: “Who are the characters in this story?”

Ask: “What happened first in the story? Then what happened? then what happened?” — and so on, until (with your help and prompting as needed) the children have remembered what happened in the story.

Determine where the stage area will be. Children who are not actors may sit facing the stage area.

The lead teacher reads the story, prompting actors as needed to act out their parts. Actors do not have to repeat dialogue, although some of them will want to do so. The lead teacher may wish to simplify the story on the fly, to make it easier to act out.

Once again, remember to take photos of the skit, and print them out from next week.

IV/ Conversation about the story

Sit back down in a group.

Ask some general questions: “What was the best part of the story? Who was your favorite character? Who was your least favorite character?” — or questions you come up with on your own.

There are some resemblances between this creation story and last week’s creation story. You might want to see if the children notice these similarities. If you wish, review last week’s story by asking if any of the children remember how Izanagi and Izanami created the earth; how is that similar to the way Obatala created the earth in this story?

You can continue the conversation in any way you wish.

V/ Two optional activities

A. Play an African game

If you have the traditional African game “Mancala,” this would be a fun game to play with the children. Mancala was played in many African nations, and enslaved Africans played it when they were taken to the Americas (see this dissertation for more info). So like the Yoruba religions, Mancala belongs to the wider African diaspora. You could talk about how the game board looks a little like the divination shown above.

If you don’t already have this game, it’s available on Etsy with prices ranging from $11 on up (2024 prices). Or ask your community if you can borrow it from someone.

B. Draw the Sankofa bird

The Sankofa has been a common symbol in Akan art, and has also become a widely used symbol in the African diaspora. For an example of the Sankofa bird symbol, see the photo above, and the drawing below. Having the children draw their version of the Sankofa helps introduce them to this important cultural symbol.

The Sankofa is depicted as a bird flying forwards while looking back; it carries an egg in its mouth as it flies. The literal translation of “Sankofa” is “to go back and get it” in the Akan language. Metaphorically, the Sankofa bird can symbolize the need to reflect on the past (looking over its shoulder symbolizes the past) in order to build the future (the egg it carries symbolizes the future).

This image released into the public domain.

VII/ Building community through play

If you don’t want to do the optional activities, you can set aside more time for play.

Game ideas to build community through play: “Duck, Duck, Goose” (yes, this age group finds this game amusing) or other games.

VIII/ Closing circle

Before leaving, have the children sit or stand in a circle.

When the children are in a circle, ask them what they did today, and prompt them with questions and answers. If any parents have come to pick up their children, invite them to join the circle (so they can know what it is their children learned about this week).

After you’ve reviewed what the children learned for a couple of minutes, say together some closing words, either the ones below or something you choose. Tell the children how you enjoyed seeing them (if that’s true), and that you look forward to seeing them again next week.

Go out into the world in peace,

Be of good courage,

Hold fast to what is good,

Return to no one evil for evil.

Strengthen the fainthearted

Help the suffering;

Be patient with all,

Love all living beings.